in Jesus Christ the Saviour, who delivers from the bondage of sin by his life, doctrine and death; in the operation of the Holy Ghost; in a holy, universal, Christian church; in forgiveness of sins and the life everlasting. The Bible was made the sole rule, and all external authority was barred. Within a few weeks similar communities were formed at Leipzig, Dresden, Berlin, Offenbach, Worms, Wiesbaden and elsewhere; and at a “council” convened at Leipzig at Easter 1845, twenty-seven congregations were represented by delegates, of whom only two or at most three were in clerical orders.

Even before the beginning of the agitation led by Ronge, another movement fundamentally distinct, though in some respects similar, had been originated at Schneidemühl, Posen, under the guidance of Johann Czerski (1813–1893), also a priest, who had come into collision with the church authorities on the then much discussed question of mixed marriages, and also on that of the celibacy of the clergy. The result had been his suspension from office in March 1844; his public withdrawal, along with twenty-four adherents, from the Roman communion in August; his excommunication; and the formation, in October, of a “Christian Catholic” congregation which, while rejecting clerical celibacy, the use of Latin in public worship, and the doctrines of purgatory and transubstantiation, retained the Nicene theology and the doctrine of the seven sacraments. Czerski had been at some of the sittings of the “German Catholic” council of Leipzig; but when a formula somewhat similar to that of Breslau had been adopted, he refused his signature because the divinity of Christ had been ignored, and he and his congregation continued to retain by preference the name of “Christian Catholics,” which they had originally assumed. Of the German Catholic congregations which had been represented at Leipzig some manifested a preference for the fuller and more positive creed of Schneidemühl, but a great majority continued to accept the comparatively rationalistic position of the Breslau school. The number of these rapidly increased, and the congregations scattered over Germany numbered nearly 200. External and internal checks, however, soon limited this advance. In Austria, and ultimately also in Bavaria, the use of the name German Catholics was officially prohibited, that of “Dissidents” being substituted, while in Prussia, Baden and Saxony the adherents of the new creed were laid under various disabilities, being suspected both of undermining religion and of encouraging the revolutionary tendencies of the age. Ronge himself was a foremost figure in the troubles of 1848; after the dissolution of the Frankfort parliament he lived for some time in London, returning in 1861 to Germany. He died at Vienna on the 26th of October 1887. In 1859 some of the German Catholics entered into corporate union with the “Free Congregations,” an association of free-thinking communities that had since 1844 been gradually withdrawing from the orthodox Protestant Church, when the united body took the title of “The Religious Society of Free Congregations.” Before that time many of the congregations which were formed in 1844 and the years immediately following had been dissolved, including that of Schneidemühl itself, which ceased to exist in 1857. There are now only about 2000 strict German Catholics, all in Saxony. The movement has been superseded by the Old Catholic (q.v.) organization.

See G. G. Gervinus, Die Mission des Deutschkatholicismus (1846); F. Kampe, Das Wesen des Deutschkatholicismus (1860); Findel, Der Deutschkatholicismus in Sachsen (1895); Carl Mirbt, in Herzog-Hauck’s Realencyk. für prot. Theol. iv. 583.

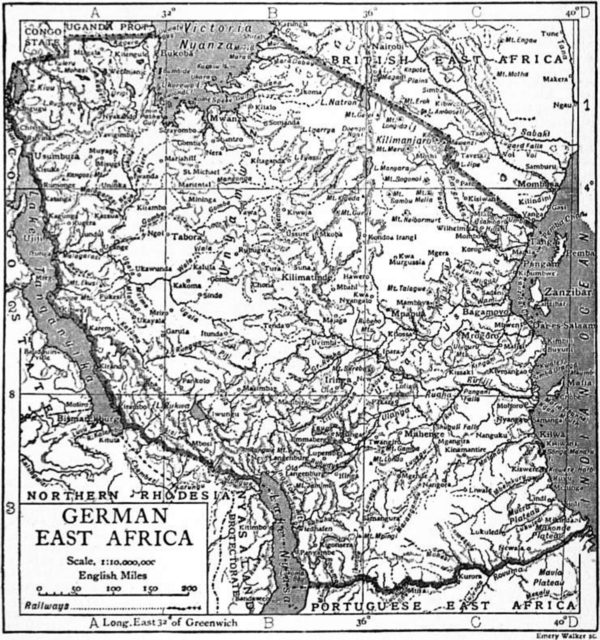

GERMAN EAST AFRICA, a country occupying the east-central portion of the African continent. The colony extends at its greatest length north to south from 1° to 11° S., and west to east from 30° to 40° E. It is bounded E. by the Indian Ocean (the coast-line extending from 4° 20′ to 10° 40′ S.), N.E. and N. by British East Africa and Uganda, W. by Belgian Congo, S.W. by British Central Africa and S. by Portuguese East Africa.

Area and Boundaries.—On the north the boundary line runs N.W. from the mouth of the Umba river to Lake Jipe and Mount Kilimanjaro including both in the protectorate, and thence to Victoria Nyanza, crossing it at 1° S., which parallel it follows till it reaches 30° E. In the west the frontier is as follows: From the point of intersection of 1° S. and 30° E., a line running S. and S.W. to the north-west end of Lake Kivu, thence across that lake near its western shore, and along the river Rusizi, which issues from it, to the spot where the Rusizi enters the north end of Lake Tanganyika; along the middle line of Tanganyika to near its southern end, when it is deflected eastward to the point where the river Kalambo enters the lake (thus leaving the southern end of Tanganyika to Great Britain). From this point the frontier runs S.E. across the plateau between Lakes Tanganyika and Nyasa, in its southern section following the course of the river Songwe. Thence it goes down the middle of Nyasa as far as 11° 30′ S. The southern frontier goes direct from the last-named point eastward to the Rovuma river, which separates German and Portuguese territory. A little before the Indian Ocean is reached the frontier is deflected south so as to leave the mouth of the Rovuma in German East Africa. These boundaries include an area of about 364,000 sq. m. (nearly double the size of Germany), with a population estimated in 1910 at 8,000,000. Of