Gibbon judged civilization and progress was the measure in which the happiness of men is secured, and of that happiness he considered political freedom an essential condition. He was essentially humane; and it is worthy of notice that he was in favour of the abolition of slavery, while humane men like his friend Lord Sheffield, Dr Johnson and Boswell were opposed to the anti-slavery movement.

Bibliography.—Of the original quarto edition of The Decline and Fall, vol. i. appeared, as has already been stated, in 1776, vols. ii. and iii. in 1781 and vols. iv.-vi. (inscribed to Lord North) in 1788. In later editions vol. i. was considerably altered by the author; the others hardly at all. The number of modern reprints has been very considerable. For many years the most important and valuable English edition was that of Milman (1839 and 1845), which was reissued with many critical additions by Dr W. Smith (8 vols. 8vo, 1854 and 1872). This has now been superseded by the edition, with copious notes, by Professor J. B. Bury (7 vols. 8vo, 1896–1900). The edition in Bohn’s British Classics (7 vols., 1853) deserves mention. See also the essay on Gibbon in Sir Spencer Walpole’s Essays and Biographies (1907). As a curiosity of literature Bowdler’s edition, “adapted to the use of families and young persons,” by the expurgation of “the indecent expressions and all allusions of an improper tendency” (5 vols. 8vo, 1825), may be noticed. The French translation of Le Clerc de Septchênes, continued by Démeunier, Boulard and Cantwell (1788–1795), has been frequently reprinted in France. It seems to be certain that the portion usually attributed to Septchênes was, in part at least, the work of his distinguished pupil, Louis XVI. A new edition of the complete translation, prefaced by a letter on Gibbon’s life and character, from the pen of Suard, and annotated by Guizot, appeared in 1812 (and again in 1828). There are at least two German translations of The Decline and Fall, one by Wenck, Schreiter and Beck (1805–1807), and a second by Johann C. Sporschil (1837, new ed. 1862). The Italian translation (alluded to by Gibbon himself) was, along with Spedalieri’s Confutazione, reprinted at Milan in 1823. There is a Russian translation by Neviedomski (7 parts, Moscow, 1883–1886), and an Hungarian version of cc. 1-38 by K. Hegyessy (Pest, 1868–1869). Gibbon’s Miscellaneous Works, with Memoirs of his Life and Writings, composed by himself; illustrated from his Letters, with occasional Notes and Narrative, published by Lord Sheffield in two volumes in 1796, has been often reprinted. The new edition in five volumes (1814) contained some previously unpublished matter, and in particular the fragment on the revolutions of Switzerland. A French translation of the Miscellaneous Works by Marigné appeared at Paris in 1798. There is also a German translation (Leipzig, 1801). It may be added that a special translation of the chapter on Roman Law (Gibbon’s historische Übersicht des römischen Rechts) was published by Hugo at Göttingen in 1839, and has frequently been used as a text-book in German universities. This chapter has also appeared in Polish (Cracow, 1844) and Greek (Athens, 1840). The centenary of Gibbon’s death was celebrated in 1894 under the auspices of the Royal Historical Society: Proceedings of the Gibbon Commemoration, 1794–1894, by R. H. T. Ball (1895). (J. B. B.)

GIBBON, the collective title of the smaller man-like apes

of the Indo-Malay countries, all of which may be included in

the single genus Hylobates. Till recently these apes have been

generally included in the same family (Simiidae) with the

chimpanzee, gorilla and orang-utan, but they are now regarded

by several naturalists as representing a family by themselves—the

Hylobatidae. One of the distinctive features of this family

is the presence of small naked callosities on the buttocks;

another being a difference in the number of vertebrae and ribs

as compared with those of the Simiidae. The extreme length

of the limbs and the absence of a tail are other features of these

small apes, which are thoroughly arboreal in their habits, and

make the woods resound with their unearthly cries at night.

In agility they are unsurpassed; in fact they are stated to be so

swift in their movements as to be able to capture birds on the

wing with their paws. When they descend to the ground—which

they must often do in order to obtain water—they frequently

walk in the upright posture, either with the hands crossed behind

the neck, or with the knuckles resting on the ground. Their

usual food consists of leaves and fruits. Gibbons may be divided

into two groups, the one represented by the siamang, Hylobates

(Symphalangus) syndactylus, of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula,

and the other by a number of closely allied species. The union

of the index and middle fingers by means of a web extending

as far as the terminal joints is the distinctive feature of the

siamang, which is the largest of the group, and black in colour

with a white frontal band. Black or puce-grey is the prevailing

colour in the second group, of which the hulock (H. hulock) of

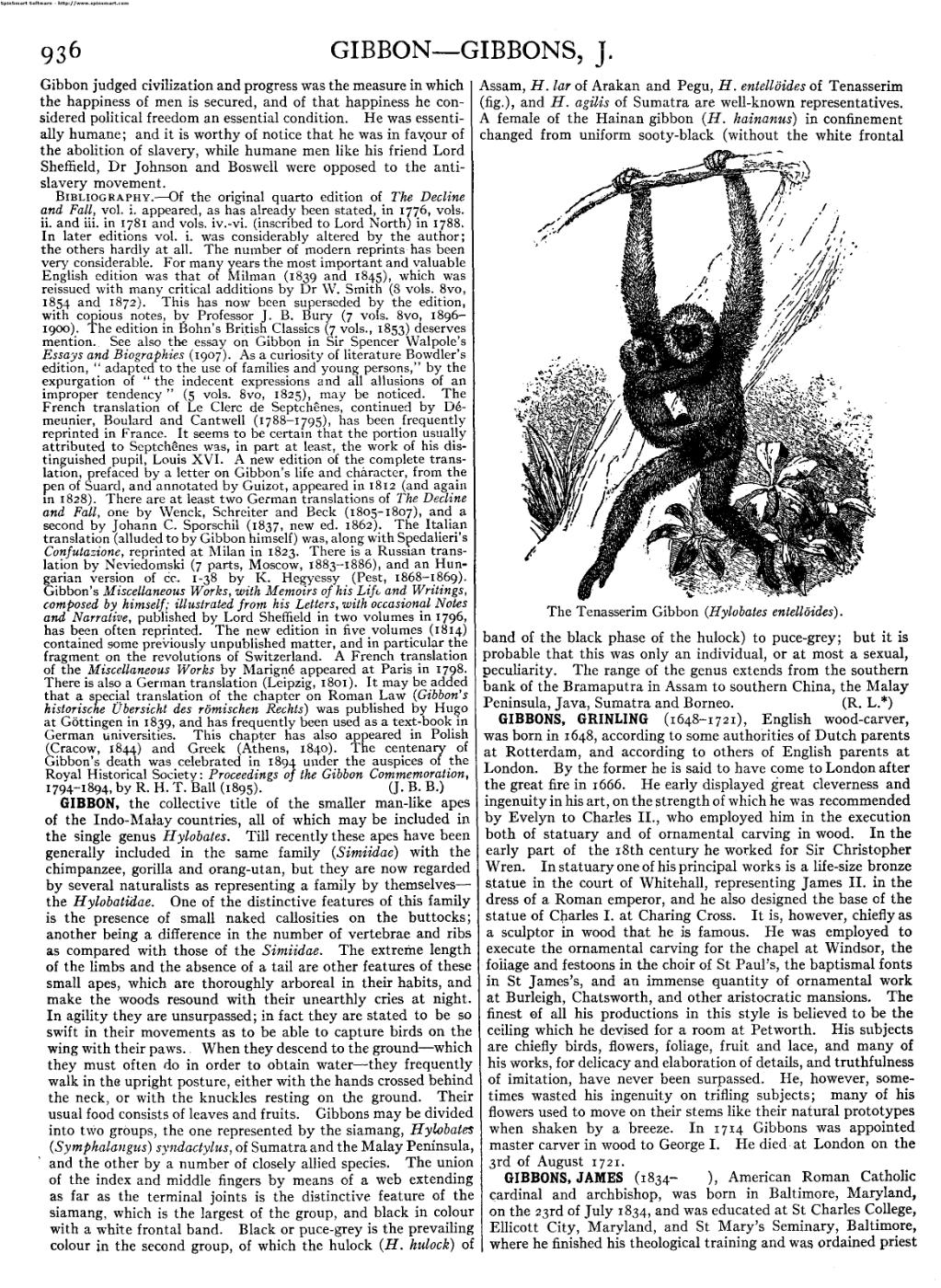

Assam, H. lar of Arakan and Pegu, H. entellöides of Tenasserim

(fig.), and H. agilis of Sumatra are well-known representatives.

A female of the Hainan gibbon (H. hainanus) in confinement

changed from uniform sooty-black (without the white frontal

band of the black phase of the hulock) to puce-grey; but it is

probable that this was only an individual, or at most a sexual,

peculiarity. The range of the genus extends from the southern

bank of the Bramaputra in Assam to southern China, the Malay

Peninsula, Java, Sumatra and Borneo.

(R. L.*)

|

| The Tenasserim Gibbon (Hylobates entellöides). |

GIBBONS, GRINLING (1648–1721), English wood-carver,

was born in 1648, according to some authorities of Dutch parents

at Rotterdam, and according to others of English parents at

London. By the former he is said to have come to London after

the great fire in 1666. He early displayed great cleverness and

ingenuity in his art, on the strength of which he was recommended

by Evelyn to Charles II., who employed him in the execution

both of statuary and of ornamental carving in wood. In the

early part of the 18th century he worked for Sir Christopher

Wren. In statuary one of his principal works is a life-size bronze

statue in the court of Whitehall, representing James II. in the

dress of a Roman emperor, and he also designed the base of the

statue of Charles I. at Charing Cross. It is, however, chiefly as

a sculptor in wood that he is famous. He was employed to

execute the ornamental carving for the chapel at Windsor, the

foliage and festoons in the choir of St Paul’s, the baptismal fonts

in St James’s, and an immense quantity of ornamental work

at Burleigh, Chatsworth, and other aristocratic mansions. The

finest of all his productions in this style is believed to be the

ceiling which he devised for a room at Petworth. His subjects

are chiefly birds, flowers, foliage, fruit and lace, and many of

his works, for delicacy and elaboration of details, and truthfulness

of imitation, have never been surpassed. He, however, sometimes

wasted his ingenuity on trifling subjects; many of his

flowers used to move on their stems like their natural prototypes

when shaken by a breeze. In 1714 Gibbons was appointed

master carver in wood to George I. He died at London on the

3rd of August 1721.

GIBBONS, JAMES (1834– ), American Roman Catholic

cardinal and archbishop, was born in Baltimore, Maryland,

on the 23rd of July 1834, and was educated at St Charles College,

Ellicott City, Maryland, and St Mary’s Seminary, Baltimore,

where he finished his theological training and was ordained priest