endless chain, or are placed in a heated kiln in which the fire is allowed gradually to die out. The second system is especially used for annealing large and heavy objects. The manufacture of table-ware is carried on by small gangs of men and boys. In England each “gang” or “chair” consists of three men and one boy. In works, however, in which most of the goods are moulded, and where less skilled labour is required, the proportion of boy labour is increased. There are generally two shifts of workmen, each shift working six hours, and the work is carried on continuously from Monday morning until Friday morning. Directly work is suspended the glass remaining in the crucibles is ladled into water, drained and dried. It is then mixed with the glass mixture and broken glass (“cullet”), and replaced in the crucibles. The furnaces are driven to a white heat in order to fuse the mixture and expel bubbles of gas and air. Before work begins the temperature is lowered sufficiently to render the glass viscous. In the viscous state a mass of glass can be coiled upon the heated end of an iron rod, and if the rod is hollow can be blown into a hollow bulb. The tools used are extremely primitive—hollow iron blowing-rods, solid rods for holding vessels during manipulation, spring tools, resembling sugar-tongs in shape, with steel or wooden blades for fashioning the viscous glass, callipers, measure-sticks, and a variety of moulds of wood, carbon, cast iron, gun-metal and plaster of Paris (figs. 16 and 17). The most important tool, however, is the bench or “chair” on which the workman sits, which serves as his lathe. He sits between two rigid parallel arms, projecting forwards and backwards and sloping slightly from back to front. Across the arms he balances the iron rod to which the glass bulb adheres, and rolling it backwards and forwards with the fingers of his left hand fashions the glass between the blades of his sugar-tongs tool, grasped in his right hand. The hollow bulb is worked into the shape it is intended to assume, partly by blowing, partly by gravitation, and partly by the workman’s tool. If the blowing iron is held vertically with the bulb uppermost the bulb becomes flattened and shallow, if the bulb is allowed to hang downwards it becomes elongated and reduced in diameter, and if the end of the bulb is pierced and the iron is held horizontally and sharply trundled, as a mop is trundled, the bulb opens out into a flattened disk.

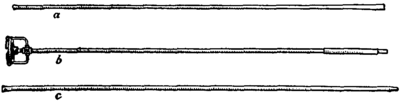

Fig. 16.—Pontils and Blowing Iron.

a, Puntee; b, spring puntee; c, blowing iron.

Fig. 17.—Shaping and Measuring Tools.

| d, “Sugar-tongs” tool with wooden ends. |

f, Pincers, |

| g, Scissors. | |

| e, e, “Sugar-tongs” tools with cutting edges. |

h, Battledore. |

| i,Marking compass. |

During the process of manipulation, whether on the chair or whilst the glass is being reheated, the rod must be constantly and gently trundled to prevent the collapse of the bulb or vessel. Every natural development of the spherical form can be obtained by blowing and fashioning by hand. A non-spherical form can only be produced by blowing the hollow bulb into a mould of the required shape. Moulds are used both for giving shape to vessels and also for impressing patterns on their surface. Although spherical forms can be obtained without the use of moulds, moulds are now largely used for even the simplest kinds of table-ware in order to economize time and skilled labour. In France, Germany and the United States it is rare to find a piece of table-ware which has not received its shape in a mould. The old and the new systems of making a wine-glass illustrate almost all the ordinary processes of glass working. Sufficient glass is first “gathered” on the end of a blowing iron to form the bowl of the wine-glass. The mere act of coiling an exact weight of molten glass round the end of a rod 4 ft. in length requires considerable skill. The mass of glass is rolled on a polished slab of iron, the “marvor,” to solidify it, and it is then slightly hollowed by blowing. Under the old system the form of the bowl is gradually developed by blowing and by shaping the bulb with the sugar-tongs tool. The leg is either pulled out from the substance of the base of the bowl, or from a small lump of glass added to the base. The foot starts as a small independent bulb on a separate blowing iron. One extremity of this bulb is made to adhere to the end of the leg, and the other extremity is broken away from its blowing iron. The fractured end is heated, and by the combined action of heat and centrifugal force opens out into a flat foot. The bowl is now severed from its blowing iron and the unfinished wine-glass is supported by its foot, which is attached to the end of a working rod by a metal clip or by a seal of glass. The fractured edge of the bowl is heated, trimmed with scissors and melted so as to be perfectly smooth and even, and the bowl itself receives its final form from the sugar-tongs tool.

Under the new system the bowl is fashioned by blowing the slightly hollowed mass of glass into a mould. The leg is formed and a small lump of molten glass is attached to its extremity to form the foot. The blowing iron is constantly trundled, and the small lump of glass is squeezed and flattened into the shape of a foot, either between two slabs of wood hinged together, or by pressure against an upright board. The bowl is severed from the blowing iron, and the wine-glass is sent to the annealing oven with a bowl, longer than that of the finished glass, and with a rough fractured edge. When the glass is cold the surplus is removed either by grinding, or by applying heat to a line scratched with a diamond round the bowl. The fractured edge is smoothed by the impact of a gas flame.

In the manufacture of a wine-glass the ductility of glass is illustrated on a small scale by the process of pulling out the leg. It is more strikingly illustrated in the manufacture of glass cane and tube. Cane is produced from a solid mass of molten glass, tube from a mass hollowed by blowing. One workman holds the blowing iron with the mass of glass attached to it, and another fixes an iron rod by means of a seal of glass to the extremity of the mass. The two workmen face each other and walk backwards. The diameter of the cane or tube is regulated by the weight of glass carried, and by the distance covered by the two workmen. It is a curious property of viscous glass that whatever form is given to the mass of glass before it is drawn out is retained by the finished cane or tube, however small its section may be. Owing to this property, tubes or canes can be produced with a square, oblong, oval or triangular section. Exceedingly fine canes of milk-white glass play an important part in the masterpieces produced by the Venetian glass-makers of the 16th century. Vases and drinking cups were produced of extreme lightness, in the walls of which were embedded patterns rivalling lace-work in fineness and intricacy. The canes from which the patterns are formed are either simple or complex. The latter are made by dipping a small mass of molten colourless glass into an iron cup around the inner wall of which short lengths of white cane have been arranged at