blade on to the sheath, which occurs in all the Bambuseae

(except Planotia) and in Spartina stricta; and the interposition

of a petiole between the sheath and the blade, as in bamboos,

Leptaspis, Pharus, Pariana, Lophatherum and others. In the

latter case the leaf usually becomes oval, ovate or even cordate

or sagittate, but these forms are found in sessile leaves also

(Olyra, Panicum). The venation is strictly parallel, the midrib

usually strong, and the other ribs more slender. In Anomochloa

there are several nearly equal ribs and in some broad-leaved

grasses (Bambuseae, Pharus, Leptaspis) the venation becomes

tesselated by transverse

connecting veins. The

tissue is often raised

above the veins, forming

longitudinal ridges,

generally on the upper

face; the stomata are in

lines in the intervening

furrows. The thick prominent

veins in Agropyrum

occupy the whole

upper surface of the leaf. Epidermal appendages are rare,

the most frequent being marginal, saw-like, cartilaginous

teeth, usually minute, but occasionally (Danthonia scabra,

Panicum serratum) so large as to give the margin a serrate

appearance. The leaves are occasionally woolly, as in Alopecurus

lanatus and one or two Panicums. The blade is often twisted,

frequently so much so that the upper and under faces become

reversed. In dry-country grasses the blades are often folded

on the midrib, or rolled up. The rolling is effected by bands of

large wedge-shaped cells—motor-cells—between the nerves,

the loss of turgescence by which, as the air dries, causes the

blade to curl towards the face on which they occur. The rolling

up acts as a protection from too great loss of water, the exposed

surface being specially protected to this end by a strong cuticle,

the majority or all of the stomata occurring on the protected

surface. The stiffness of the blade, which becomes very marked

in dry-country grasses, is due to the development of girders of

thick-walled mechanical tissue which follow the course of all

or the principal veins (fig. 2).

| |

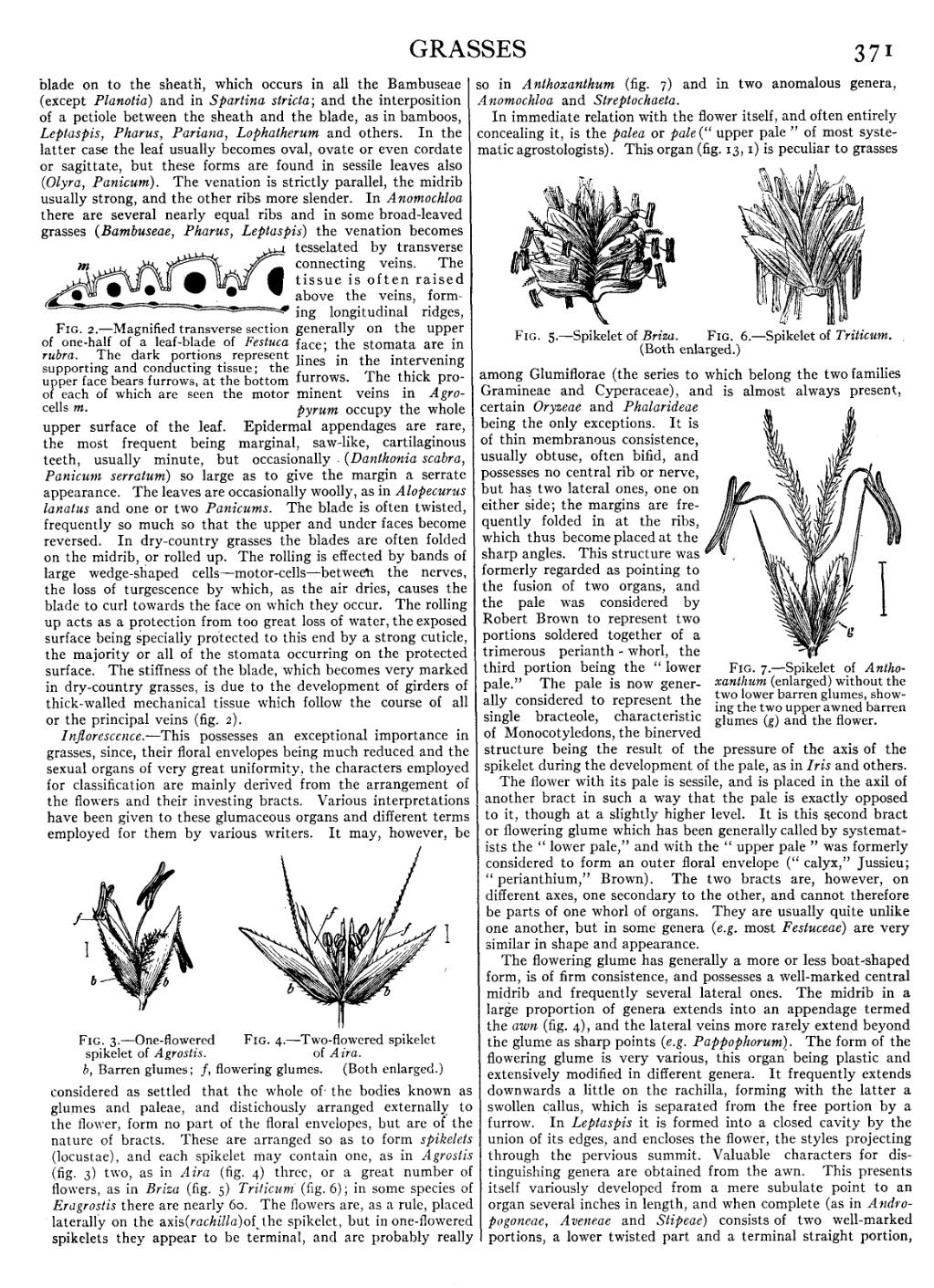

| Fig. 3.—One-flowered spikelet of Agrostis. |

Fig. 4.—Two-flowered spikelet of Aira. |

| b, Barren glumes; f, flowering glumes. (Both Enlarged.) | |

Inflorescence.—This possesses an exceptional importance in grasses, since, their floral envelopes being much reduced and the sexual organs of very great uniformity, the characters employed for classification are mainly derived from the arrangement of the flowers and their investing bracts. Various interpretations have been given to these glumaceous organs and different terms employed for them by various writers. It may, however, be considered as settled that the whole of the bodies known as glumes and paleae, and distichously arranged externally to the flower, form no part of the floral envelopes, but are of the nature of bracts. These are arranged so as to form spikelets (locustae), and each spikelet may contain one, as in Agrostis (fig. 3) two, as in Aira (fig. 4) three, or a great number of flowers, as in Briza (fig. 5) Triticum (fig. 6); in some species of Eragrostis there are nearly 60. The flowers are, as a rule, placed laterally on the axis (rachilla) of the spikelet, but in one-flowered spikelets they appear to be terminal, and are probably really so in Anthoxanthum (fig. 7) and in two anomalous genera, Anomochloa and Streptochaeta.

| |

| Fig. 5.—Spikelet of Briza. | Fig. 6.—Spikelet of Triticum. |

| (Both enlarged.) | |

|

| Fig. 7.—Spikelet of Anthoxanthum (enlarged) without the two lower barren glumes, showing the two upper awned barren glumes (g) and the flower. |

In immediate relation with the flower itself, and often entirely concealing it, is the palea or pale (“upper pale” of most systematic agrostologists). This organ (fig. 13, 1) is peculiar to grasses among Glumiflorae (the series to which belong the two families Gramineae and Cyperaceae), and is almost always present, certain Oryzeae and Phalarideae being the only exceptions. It is of thin membranous consistence, usually obtuse, often bifid, and possesses no central rib or nerve, but has two lateral ones, one on either side; the margins are frequently folded in at the ribs, which thus become placed at the sharp angles. This structure was formerly regarded as pointing to the fusion of two organs, and the pale was considered by Robert Brown to represent two portions soldered together of a trimerous perianth-whorl, the third portion being the “lower pale.” The pale is now generally considered to represent the single bracteole, characteristic of Monocotyledons, the binerved structure being the result of the pressure of the axis of the spikelet during the development of the pale, as in Iris and others.

The flower with its pale is sessile, and is placed in the axis of another bract in such a way that the pale is exactly opposed to it, though at a slightly higher level. It is this second bract or flowering glume which has been generally called by systematists the “lower pale,” and with the “upper pale” was formerly considered to form an outer floral envelope (“calyx,” Jussieu; “perianthium,” Brown). The two bracts are, however, on different axes, one secondary to the other, and cannot therefore be parts of one whorl of organs. They are usually quite unlike one another, but in some genera (e.g. most Festuceae) are very similar in shape and appearance.

|

| Fig. 8.—Spikelet of Stipa pennata. The pair of barren glumes (b) are separated from the flowering glume, which bears a long awn, twisted below the knee and feathery above. About 34 nat. size. |

The flowering glume has generally a more or less boat-shaped form, is of firm consistence, and possesses a well-marked central midrib and frequently several lateral ones. The midrib in a large proportion of genera extends into an appendage termed the awn (fig. 4), and the lateral veins more rarely extend beyond the glume as sharp points (e.g. Pappophorum). The form of the flowering glume is very various, this organ being plastic and extensively modified in different genera. It frequently extends downwards a little on the rachilla, forming with the latter a swollen callus, which is separated from the free portion by a furrow. In Leptaspis it is formed into a closed cavity by the union of its edges, and encloses the flower, the styles projecting through the pervious summit. Valuable characters for distinguishing genera are obtained from the awn. This presents itself variously developed from a mere subulate point to an organ several inches in length, and when complete (as in Andropogoneae, Aveneae and Stipeae) consists of two well-marked portions, a lower twisted part and a terminal straight portion,