(liliaceous) perianth, the outer whorl of these being suppressed as well as the posterior member of the inner whorl. This latter is present almost constantly in Stipeae and Bambuseae, which have three lodicules, and in the latter group they are occasionally more numerous. In Anomochloa they are represented by hairs. In Streptochaeta there are six lodicules, alternately arranged in two whorls. Sometimes, as in Anthoxanthum, they are absent. In Melica there is one large anterior lodicule resulting presumably from the union of the two which are present in allied genera. Professor E. Hackel, however, regards this as an undivided second pale, which in the majority of the grasses is split in halves, and the posterior lodicule, when present, as a third pale. On this view the grass-flower has no perianth. The function of the lodicules is the separation of the pale and glume to allow the protrusion of stamens and stigmas; they effect this by swelling and thus exerting pressure on the base of these two structures. Where, as in Anthoxanthum, there are no lodicules, pale and glume do not become laterally separated, and the stamens and stigmas protrude only at the apex of the floret (fig. 7). Grass-flowers are usually hermaphrodite, but there are very many exceptions. Thus it is common to find one or more imperfect (usually male) flowers in the same spikelet with bisexual ones, and their relative position is important in classification. Holcus and Arrhenatherum are examples in English grasses; and as a rule in species of temperate regions separation of the sexes is not carried further. In warmer countries monoecious and dioecious grasses are more frequent. In such cases the male and female spikelets and inflorescence may be very dissimilar, as in maize, Job’s tears, Euchlaena, Spinifex, &c.; and in some dioecious species this dissimilarity has led to the two sexes being referred to different genera (e.g. Anthephora axilliflora is the female of Buchloe dactyloides, and Neurachne paradoxa of a species of Spinifex). In other grasses, however, with the sexes in different plants (e.g. Brizopyrum, Distichlis, Eragrostis capitala, Gynerium), no such dimorphism obtains. Amphicarpum is remarkable in having cleistogamic flowers borne on long radical subterranean peduncles which are fertile, whilst the conspicuous upper paniculate ones, though apparently perfect, never produce fruit. Something similar occurs in Leersia oryzoides, where the fertile spikelets are concealed within the leaf-sheaths.

Androecium.—In the vast majority there are three stamens alternating with the lodicules, and therefore one anterior, i.e. opposite the flowering glume, the other two being posterior and in contact with the palea (fig. 13, 1 and 2). They are hypogynous, and have long and very delicate filaments, and large, linear or oblong two-celled anthers, dorsifixed and ultimately very versatile, deeply indented at each end, and commonly exserted and pendulous. Suppression of the anterior stamen sometimes occurs (e.g. Anthoxanthum, fig. 7), or the two posterior ones may be absent (Uniola, Cinna, Phippsia, Festuca bromoides). There is in some genera (Oryza, most Bambuseae) another row of three stamens, making six in all (fig. 13, 3); and Anomochloa and Tetrarrhena possess four. The stamens become numerous (ten to forty) in the male flowers of a few monoecious genera (Pariana, Luziola). In Ochlandra they vary from seven to thirty, and in Gigantochloa they are monadelphous.

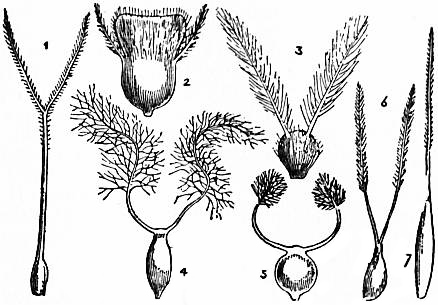

Gynoecium.—The pistil consists of a single carpel, opposite the pale in the median plane of the spikelet. The ovary is small, rounded to elliptical, and one-celled, and contains a single slightly bent ovule sessile on the ventral suture (that is, springing from the back of the ovary); the micropyle points downwards. It bears usually two lateral styles which are quite distinct or connate at the base, sometimes for a greater length (fig. 14, 1), each ends in a densely hairy or feathery stigma (fig. 14). Occasionally there is but a single style, as in Nardus (fig. 14, 7), which corresponds to the midrib of the carpel. The very long and apparently simple stigma of maize arises from the union of two. Many of the bamboos have a third, anterior, style.

|

| Fig. 14.—Pistils of grasses (much enlarged). 1, Alopecurus; 2, Bromus; 3, Arrhenatherum; 4, Glyceria; 5, Melica; 6, Mibora; 7, Nardus. |

Comparing the flower of Gramineae with the general monocotyledonous plan as represented by Liliaceae and other families (fig. 15), it will be seen to differ in the absence of the outer row and the posterior member of the inner row of the perianth-leaves, of the whole inner row of stamens, and of the two lateral carpels, whilst the remaining members of the perianth are in a rudimentary condition. But each or any of the usually missing organs are to be found normally in different genera, or as occasional developments.

Pollination.—Grasses are generally wind-pollinated, though self-fertilization sometimes occurs. A few species, as we have seen, are monoecious or dioecious, while many are polygamous (having unisexual as well as bisexual flowers as in many members of the tribes Andropogoneae, fig. 18, and Paniceae), and in these the male flower of a spikelet always blooms later than the hermaphrodite, so that its pollen can only effect cross-fertilization upon other spikelets in the same or another plant. Of those with only bisexual flowers, many are strongly protogynous (the stigmas protruding before the anthers are ripe), such as Alopecurus and Anthoxanthum (fig. 7), but generally the anthers protrude first and discharge the greater part of their pollen before the stigmas appear. The filaments elongate rapidly at flowering-time, and the lightly versatile anthers empty an abundance of finely granular smooth pollen through a longitudinal slit. Some flowers, such as rye, have lost the power of effective self-fertilization, but in most cases both forms, self- and cross-fertilization, seem to be possible. Thus the species of wheat are usually self-fertilized, but cross-fertilization is possible since the glumes are open above, the stigmas project laterally, and the anthers empty only about one-third of their pollen in their own flower and the rest into the air. In some cultivated races of barley, cross-fertilization is precluded, as the flowers never open. Reference has already been made to cleistogamic species which occur in several genera.

|

| Fig. 16.—Fruit of Sporobolus, showing the dehiscent pericarp and seed. |

Fruit and Seed.—The ovary ripens into a usually small ovoid or rounded fruit, which is entirely occupied by the single large seed, from which it is not to be distinguished, the thin pericarp being completely united to its surface. To this peculiar fruit the term caryopsis has been applied (more familiarly “grain”); it is commonly furrowed longitudinally down one side (usually the inner, but in Coix and its allies, the outer), and an additional covering is not unfrequently provided by the adherence of the persistent palea, or even also of the flowering