the violin, and may justly claim to be its immediate predecessor[1] not so much through the viols which were the outcome of the Minnesinger fiddle with sloping shoulders, as through the intermediary of the Italian lyra, a guitar-shaped bowed instrument with from 7 to 12 strings.

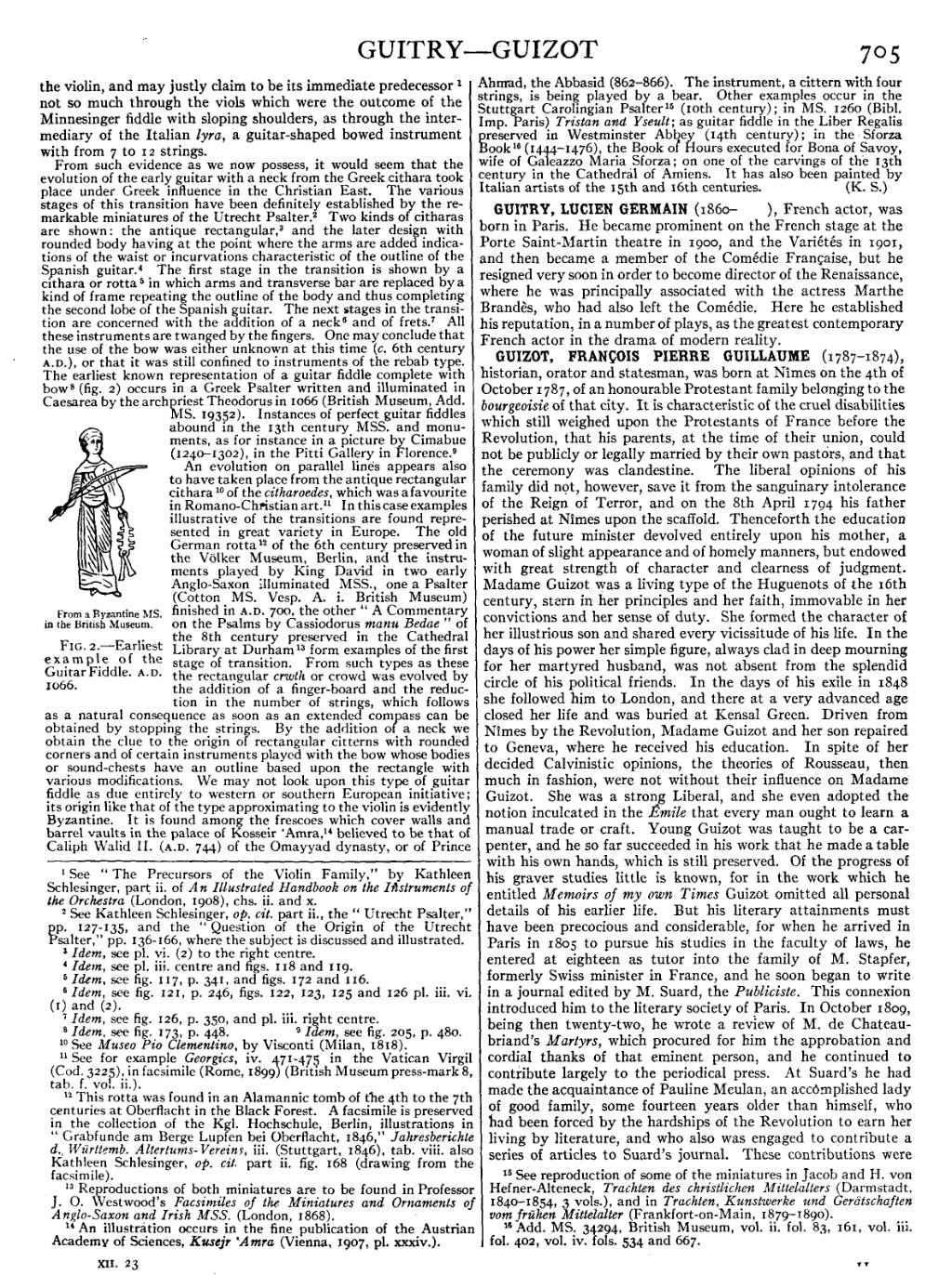

From such evidence as we now possess, it would seem that the evolution of the early guitar with a neck from the Greek cithara took place under Greek influence in the Christian East. The various stages of this transition have been definitely established by the remarkable miniatures of the Utrecht Psalter.[2] Two kinds of citharas are shown: the antique rectangular,[3] and the later design with rounded body having at the point where the arms are added indications of the waist or incurvations characteristic of the outline of the Spanish guitar.[4] The first stage in the transition is shown by a cithara or rotta[5] in which arms and transverse bar are replaced by a kind of frame repeating the outline of the body and thus completing the second lobe of the Spanish guitar. The next stages in the transition are concerned with the addition of a neck[6] and of frets.[7] All these instruments are twanged by the fingers. One may conclude that the use of the bow was either unknown at this time (c. 6th century A.D.), or that it was still confined to instruments of the rebab type. The earliest known representation of a guitar fiddle complete with bow[8] (fig. 2) occurs in a Greek Psalter written and illuminated in Caesarea by the archpriest Theodoras in 1066 (British Museum, Add. MS. 19352). Instances of perfect guitar fiddles abound in the 13th century MSS. and monuments, as for instance in a picture by Cimabue (1240–1302), in the Pitti Gallery in Florence.[9]

|

| From a Byzantine MS. in the British Museum. |

| Fig. 2.—Earliest example of the Guitar Fiddle. A.D. 1066. |

An evolution on parallel lines appears also to have taken place from the antique rectangular cithara[10] of the citharoedes, which was a favourite in Romano-Christian art.[11] In this case examples illustrative of the transitions are found represented in great variety in Europe. The old German rotta[12] of the 6th century preserved in the Völker Museum, Berlin, and the instruments played by King David in two early Anglo-Saxon illuminated MSS., one a Psalter (Cotton MS. Vesp. A. i. British Museum) finished in A.D. 700, the other “A Commentary on the Psalms by Cassiodorus manu Bedae” of the 8th century preserved in the Cathedral Library at Durham[13] form examples of the first stage of transition. From such types as these the rectangular crwth or crowd was evolved by the addition of a finger-board and the reduction in the number of strings, which follows as a natural consequence as soon as an extended compass can be obtained by stopping the strings. By the addition of a neck we obtain the clue to the origin of rectangular citterns with rounded corners and of certain instruments played with the bow whose bodies or sound-chests have an outline based upon the rectangle with various modifications. We may not look upon this type of guitar fiddle as due entirely to western or southern European initiative; its origin like that of the type approximating to the violin is evidently Byzantine. It is found among the frescoes which cover walls and barrel vaults in the palace of Kosseir ʽAmra,[14] believed to be that of Caliph Walid II. (A.D. 744) of the Omayyad dynasty, or of Prince Ahmad, the Abbasid (862–866). The instrument, a cittern with four strings, is being played by a bear. Other examples occur in the Stuttgart Carolingian Psalter[15] (10th century); in MS. 1260 (Bibl. Imp. Paris) Tristan and Yseult; as guitar fiddle in the Liber Regalis preserved in Westminster Abbey (14th century); in the Sforza Book[16] (1444–1476), the Book of Hours executed for Bona of Savoy, wife of Gaieazzo Maria Sforza; on one of the carvings of the 13th century in the Cathedral of Amiens. It has also been painted by Italian artists of the 15th and 16th centuries. (K. S.)

GUITRY, LUCIEN GERMAIN (1860–), French actor, was born in Paris. He became prominent on the French stage at the Porte Saint-Martin theatre in 1900, and the Variétés in 1901, and then became a member of the Comédie Française, but he resigned very soon in order to become director of the Renaissance, where he was principally associated with the actress Marthe Brandès, who had also left the Comédie. Here he established his reputation, in a number of plays, as the greatest contemporary French actor in the drama of modern reality.

GUIZOT, FRANÇOIS PIERRE GUILLAUME (1787–1874), historian, orator and statesman, was born at Nîmes on the 4th of October 1787, of an honourable Protestant family belonging to the bourgeoisie of that city. It is characteristic of the cruel disabilities which still weighed upon the Protestants of France before the Revolution, that his parents, at the time of their union, could not be publicly or legally married by their own pastors, and that the ceremony was clandestine. The liberal opinions of his family did not, however, save it from the sanguinary intolerance of the Reign of Terror, and on the 8th April 1794 his father perished at Nîmes upon the scaffold. Thenceforth the education of the future minister devolved entirely upon his mother, a woman of slight appearance and of homely manners, but endowed with great strength of character and clearness of judgment. Madame Guizot was a living type of the Huguenots of the 16th century, stern in her principles and her faith, immovable in her convictions and her sense of duty. She formed the character of her illustrious son and shared every vicissitude of his life. In the days of his power her simple figure, always clad in deep mourning for her martyred husband, was not absent from the splendid circle of his political friends. In the days of his exile in 1848 she followed him to London, and there at a very advanced age closed her life and was buried at Kensal Green. Driven from Nîmes by the Revolution, Madame Guizot and her son repaired to Geneva, where he received his education. In spite of her decided Calvinistic opinions, the theories of Rousseau, then much in fashion, were not without their influence on Madame Guizot. She was a strong Liberal, and she even adopted the notion inculcated in the Émile that every man ought to learn a manual trade or craft. Young Guizot was taught to be a carpenter, and he so far succeeded in his work that he made a table with his own hands, which is still preserved. Of the progress of his graver studies little is known, for in the work which he entitled Memoirs of my own Times Guizot omitted all personal details of his earlier life. But his literary attainments must have been precocious and considerable, for when he arrived in Paris in 1805 to pursue his studies in the faculty of laws, he entered at eighteen as tutor into the family of M. Stapfer, formerly Swiss minister in France, and he soon began to write in a journal edited by M. Suard, the Publiciste. This connexion introduced him to the literary society of Paris. In October 1809, being then twenty-two, he wrote a review of M. de Chateaubriand’s Martyrs, which procured for him the approbation and cordial thanks of that eminent person, and he continued to contribute largely to the periodical press. At Suard’s he had made the acquaintance of Pauline Meulan, an accomplished lady of good family, some fourteen years older than himself, who had been forced by the hardships of the Revolution to earn her living by literature, and who also was engaged to contribute a series of articles to Suard’s journal. These contributions were

- ↑ See “The Precursors of the Violin Family,” by Kathleen Schlesinger, part ii. of An Illustrated Handbook on the Instruments of the Orchestra (London, 1908), chs. ii. and x.

- ↑ See Kathleen Schlesinger, op. cit. part ii., the “Utrecht Psalter,” pp. 127-135, and the “Question of the Origin of the Utrecht Psalter,” pp. 136-166, where the subject is discussed and illustrated.

- ↑ Idem, see pl. vi. (2) to the right centre.

- ↑ Idem, see pl. iii. centre and figs. 118 and 119.

- ↑ Idem, see fig. 117, p. 341, and figs. 172 and 116.

- ↑ Idem, see fig. 121, p. 246, figs. 122, 123, 125 and 126 pi. iii. vi. (1) and (2).

- ↑ Idem, see fig. 126, p. 350, and pl. iii. right centre.

- ↑ Idem, see fig. 173, p. 448.

- ↑ Idem, see fig. 205, p. 480.

- ↑ See Museo Pio Clementino, by Visconti (Milan, 1818).

- ↑ See for example Georgics, iv. 471-475 in the Vatican Virgil (Cod. 3225), in facsimile (Rome, 1899) (British Museum press-mark 8, tab. f. vol. ii.).

- ↑ This rotta was found in an Alamannic tomb of the 4th to the 7th centuries at Oberflacht in the Black Forest. A facsimile is preserved in the collection of the Kgl. Hochschule, Berlin, illustrations in “Grabfunde am Berge Lupfen bei Oberflacht, 1846,” Jahresberichte d. Württemb. Altertums-Vereins, iii. (Stuttgart, 1846), tab. viii. also Kathleen Schlesinger, op. cit. part ii. fig. 168 (drawing from the facsimile).

- ↑ Reproductions of both miniatures are to be found in Professor J. O. Westwood’s Facsimiles of the Miniatures and Ornaments of Anglo-Saxon and Irish MSS. (London, 1868).

- ↑ An illustration occurs in the fine publication of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Kusejr ʽAmra (Vienna, 1907, pi. xxxiv.).

- ↑ See reproduction of some of the miniatures in Jacob and H. von Hefner-Alteneck, Trachten des christlichen Mittelalters (Darmstadt, 1840–1854, 3 vols.), and in Trachten, Kunstwerke und Gerätschaften vom frühen Mittelalter (Frankfort-on-Main, 1879–1890).

- ↑ Add. MS. 34294, British Museum, vol. ii. fol. 83, 161, vol. iii. fol. 402, vol. iv. fols. 534 and 667.