is adapted for the narrow rows of grain crops and is also convertible into a root-hoe. In the lever-hoe, which is largely used in grain crops, the blades may be raised and lowered by means of a lever. The horse-drawn hoe is steered by means of handles in the rear, but its successful working depends on accurate drilling of the seed, because unless the rows are parallel the roots of the plants are liable to be cut and the foliage injured. Thus Jethro Tull (17th century), with whose name the beginning of the practice of horse-hoeing is principally connected, used the drill which he invented as an essential adjunct in the so-called “Horse-hoeing Husbandry” (see Agriculture).

|

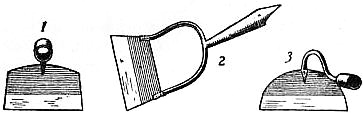

| Fig. 1.—Three Forms of Manual Hoe. |

|

| Fig. 2.—Martin’s One-Row Horse Hoe. |

|

| Fig. 3.—Martin’s General Purpose Steerage Horse Hoe. |

HOEFNAGEL, JORIS (1545–1601), Dutch painter and engraver,

the son of a diamond merchant, was born at Antwerp. He

travelled abroad, making drawings from archaeological subjects,

and was a pupil of Jan Bol at Mechlin. He was afterwards

patronized by the elector of Bavaria at Munich, where he stayed

eight years, and by the Emperor Rudolph at Prague. He died

at Vienna in 1601. He is famous for his miniature work, especially

on a missal in the imperial library at Vienna; he painted

animals and plants to illustrate works on natural history;

and his engravings (especially for Braun’s Civitates orbis

terrarum, 1572, and Ortelius’s Theatrum orbis terrarum, 1570)

give him an interesting place among early topographical

draughtsmen.

HOF, a town of Germany, in the Bavarian province of Upper

Franconia, beautifully situated on the Saale, on the north-eastern

spurs of the Fichtelgebirge, 103 m. S.W. of Leipzig

on the main line of railway to Regensburg and Munich. Pop.

(1885) 22,257; (1905) 36,348. It has one Roman Catholic

and three Protestant churches (among the latter that of St

Michael, which was restored in 1884), a town hall of 1563, a

gymnasium with an extensive library, a commercial school

and a hospital founded in 1262. It is the seat of various flourishing

industries, notably woollen, cotton and jute spinning, jute

weaving, and the manufacture of cotton and half-woollen

fabrics. It has also dye-works, flour-mills, saw-mills, breweries,

iron-works, and manufactures of machinery, iron and tin wares,

chemicals and sugar. In the neighbourhood there are large

marble quarries and extensive iron mines. Hof, originally

called Regnitzhof, was built about 1080. It was held for some

time by the dukes of Meran, and was sold in 1373 to the burgraves

of Nuremberg. The cloth manufacture introduced into

it in the 15th century, and the manufacture of veils begun

in the 16th century, greatly promoted its prosperity, but it

suffered severely in the Albertine and Hussite wars as well

as in the Thirty Years’ War. In 1792 it came into the possession

of Prussia; in 1806 it fell to France; and in 1810 it was incorporated

with Bavaria. In 1823 the greater part of the town

was destroyed by fire.

See Ernst, Geschichte und Beschreibung des Bezirks und der Stadt Hof (1866); Tillmann, Die Stadt Hof und ihre Umgebung (Hof, 1899), and C. Meyer, Quellen zur Geschichte der Stadt Hof (1894–1896).

HOFER, ANDREAS (1767–1810), Tirolese patriot, was born

on the 22nd of November 1767 at St Leonhard, in the Passeier

valley. There his father kept an inn known as “am Sand,”

which Hofer inherited, and on that account he was popularly

known as the “Sandwirth.” In addition to this he carried on

a trade in wine and horses with the north of Italy, acquiring

a high reputation for intelligence and honesty. In the wars

against the French from 1796 to 1805 he took part, first as a

sharp-shooter and afterwards as a captain of militia. By the

treaty of Pressburg (1805) Tirol was transferred from Austria

to Bavaria, and Hofer, who was almost fanatically devoted to

the Austrian house, became conspicuous as a leader of the

agitation against Bavarian rule. In 1808 he formed one of a

deputation who went to Vienna, at the invitation of the archduke

John, to concert a rising; and when in April 1809 the

Tirolese rose in arms, Hofer was chosen commander of the

contingent from his native valley, and inflicted an overwhelming

defeat on the Bavarians at Sterzing (April 11). This victory,

which resulted in the temporary reoccupation of Innsbruck

by the Austrians, made Hofer the most conspicuous of the

insurgent leaders. The rapid advance of Napoleon, indeed,

and the defeat of the main Austrian army under the archduke

Charles, once more exposed Tirol to the French and Bavarians,

who reoccupied Innsbruck. The withdrawal of the bulk of

the troops, however, gave the Tirolese their chance again;

after two battles fought on the Iselberg (May 25 and 29) the

Bavarians were again forced to evacuate the country, and Hofer

entered Innsbruck in triumph. An autograph letter of the

emperor Francis (May 29) assured him that no peace would be

concluded by which Tirol would again be separated from the

Austrian monarchy, and Hofer, believing his work accomplished,

returned to his home. Then came the news of the armistice

of Znaim (July 12), by which Tirol and Vorarlberg were surrendered

by Austria unconditionally and given up to the vengeance

of the French. The country was now again invaded by

40,000 French and Bavarian troops, and Innsbruck fell; but

the Tirolese once more organized resistance to the French

“atheists and freemasons,” and, after a temporary hesitation,

Hofer—on whose head a price had been placed—threw himself

into the movement. On the 13th of August, in another battle

on the Iselberg, the French under Marshal Lefebvre were routed

by the Tirolese peasants, and Hofer once more entered Innsbruck,

which he had some difficulty in saving from sack. Hofer was

now elected Oberkommandant of Tirol, took up his quarters in

the Hofburg at Innsbruck, and for two months ruled the country

in the emperor’s name. He preserved the habits of a simple

peasant, and his administration was characterized in part by

the peasant’s shrewd common sense, but yet more by a pious

solicitude for the minutest details of faith and morals. On the

29th of September Hofer received from the emperor a chain and

medal of honour, which encouraged him in the belief that Austria

did not intend again to desert him; the news of the conclusion

of the treaty of Schönbrunn (October 14), by which Tirol was

again ceded to Bavaria, came upon him as an overwhelming

surprise. The French in overpowering force at once pushed

into the country, and, an amnesty having been stipulated in

the treaty, Hofer and his companions, after some hesitation,

gave in their submission. On the 12th of November, however,