the advantage of laying the floors a little rounded, as then the

water draws off to the sides against the kerbstone, while the

centre remains dry for promenaders.

In cooler structures it becomes necessary in the dull season of the year to prevent the slopping of water over the plants or on the floor, as this tends to cause “damping off,”—the stems assuming a state of mildewy decay, which not infrequently, if it once attacks a plant, will destroy it piece by piece. For the same reason cleanliness and free ventilation under favourable weather conditions are of great importance.

Pruning.—Pruning is a very important operation in the fruit garden, its object being twofold—(1) to give form to the tree, and (2) to induce the free production of flower buds as the precursors of a plentiful crop of fruit. To form a standard tree, either the stock is allowed to grow up with a straight stem, by cutting away all side branches up to the height required, say about 6 ft., the scion or bud being worked at that point, and the head developed therefrom; or the stock is worked close to the ground, and the young shoot obtained therefrom is allowed to grow up in the same way, being pruned in its progress to keep it single and straight, and the top being cut off when the desired height is reached, so as to cause the growth of lateral shoots. If these are three or four in number, and fairly balanced as to strength and position, little pruning will be required. The tips of unripened wood should be cut back about one-third their length at an outwardly placed bud, and the chief pruning thereafter required will be to cut away inwardly directed shoots which cross or crowd each other and tend to confuse the centre of the tree. Bushy heads should be thinned out, and those that are too large cut back so as to remodel them. If the shoots produced are not sufficient in number, or are badly placed, or very unequal in vigour, the head should be cut back moderately close, leaving a few inches only of the young shoots, which should be pruned back to buds so placed as to furnish shoots in the positions desired. When worked at the top of a stem formed of the stock, the growth from the graft or bud must be pruned in a similar way. Three or four leading shoots should be selected to pass ere long into boughs and form a well-balanced framework for the tree; these boughs, however, will soon grow beyond any artificial system the pruner may adopt.

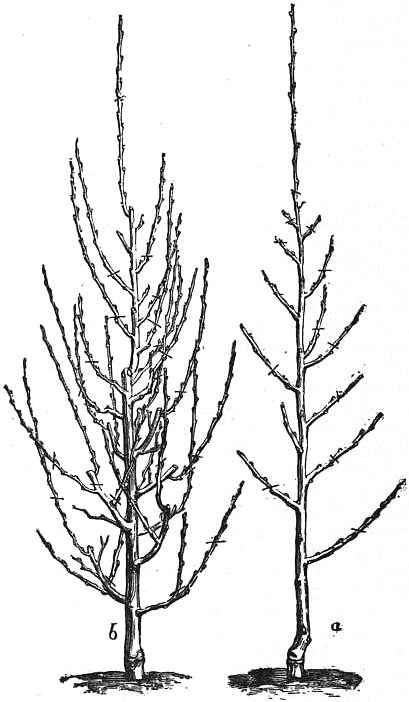

|

| Fig. 27.—Dwarf-Tree Pruning. |

To form a dwarf or bush fruit tree the stock must be worked near the ground, and the young shoot produced from the scion or bud must be cut back to whatever height it is desired the dwarf stem should be, say 112 to 2 ft. The young shoots produced from the portion of the new wood retained are to form the framework of the bush tree, and must be dealt with as in the case of standard trees. The growth of inwardly directed shoots is to be prevented, and the centre kept open, the tree assuming a cup-shaped outline. Fig. 27, reduced from M. Hardy’s excellent work, Traité de la taille des arbres fruitiers, will give a good idea how these dwarf trees are to be manipulated, a showing the first year’s development from the maiden tree after being headed back, and b the form assumed a year or two later.

|

| Fig. 28.—Pyramid Pruning. |

In forming a pyramidal tree, the lateral growths, instead of being removed, as in the standard tree, are encouraged to the utmost; and in order to strengthen them the upper part of the leading shoot is removed annually, the side branches being also shortened somewhat as the tree advances in size. In fig. 28, reduced from M. Hardy’s work, a shows a young tree with its second year’s growth, the upright shoot of the maiden tree having been moderately headed back, being left longer if the buds near the base promise to break freely, or cut shorter if they are weak and wanting in vigour. The winter pruning, carried out with the view to shape the tree into a well-grown pyramid, would be effected at the places marked by a cross line. The lowest branch would have four buds retained, the end one being on the lower side of the branch. The two next would be cut to three buds, which here also are fortunately so situated that the one to be left is on the lower side of the branches. The fourth is not cut at all owing to its shortness and weakness, its terminal bud being allowed to grow to draw strength into it. The fifth is an example where the bud to which the shoot should be cut back is badly placed; a shoot resulting from a bud left on the upper side is apt instead of growing outwards to grow erect, and lead to confusion in the form of the tree; to avoid this it is tied down in its proper place during the summer by a small twig. The upper shoots are cut closer in. Near the base of the stem are two prominent buds, which would produce two vigorous shoots, but these would be too near the ground, and the buds should therefore be suppressed; but, to strengthen the lower part, the weaker buds just above and below the lowest branch should be forced into growth, by making a transverse incision close above each. Fig. 28, b, shows what a similar tree would be at the end of the third year’s growth.