There is no routine treatment for influenza except bed. In all cases bed is advisable, because of the danger of lung complications, and in mild ones it is sufficient. Severer ones must be treated according to the symptoms. Quinine has been much used. Modern “anti-pyretic” drugs have also been extensively employed, and when applied with discretion they may be useful, but patients are not advised to prescribe them for themselves.

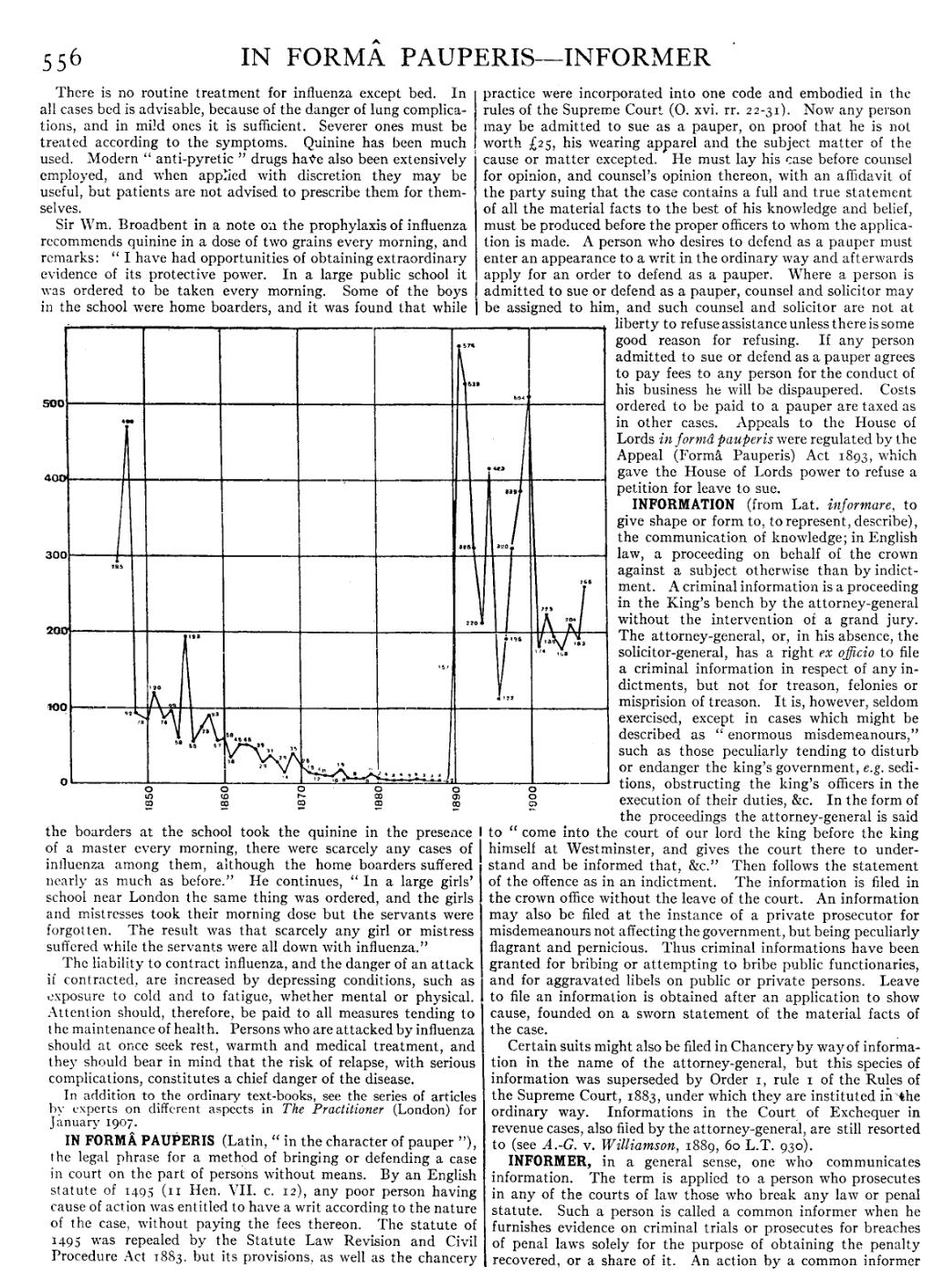

Sir Wm. Broadbent in a note on the prophylaxis of influenza recommends quinine in a dose of two grains every morning, and remarks: “I have had opportunities of obtaining extraordinary evidence of its protective power. In a large public school it was ordered to be taken every morning. Some of the boys in the school were home boarders, and it was found that while the boarders at the school took the quinine in the presence of a master every morning, there were scarcely any cases of influenza among them, although the home boarders suffered nearly as much as before.” He continues, “In a large girls’ school near London the same thing was ordered, and the girls and mistresses took their morning dose but the servants were forgotten. The result was that scarcely any girl or mistress suffered while the servants were all down with influenza.”

The liability to contract influenza, and the danger of an attack if contracted, are increased by depressing conditions, such as exposure to cold and to fatigue, whether mental or physical. Attention should, therefore, be paid to all measures tending to the maintenance of health. Persons who are attacked by influenza should at once seek rest, warmth and medical treatment, and they should bear in mind that the risk of relapse, with serious complications, constitutes a chief danger of the disease.

In addition to the ordinary text-books, see the series of articles by experts on different aspects in The Practitioner (London) for January 1907.

IN FORMÂ PAUPERIS (Latin, “in the character of pauper”),

the legal phrase for a method of bringing or defending a case

in court on the part of persons without means. By an English

statute of 1495 (11 Hen. VII. c. 12), any poor person having

cause of action was entitled to have a writ according to the nature

of the case, without paying the fees thereon. The statute of

1495 was repealed by the Statute Law Revision and Civil

Procedure Act 1883, but its provisions, as well as the chancery

practice were incorporated into one code and embodied in the

rules of the Supreme Court (O. xvi. rr. 22-31). Now any person

may be admitted to sue as a pauper, on proof that he is not

worth £25, his wearing apparel and the subject matter of the

cause or matter excepted. He must lay his case before counsel

for opinion, and counsel’s opinion thereon, with an affidavit of

the party suing that the case contains a full and true statement

of all the material facts to the best of his knowledge and belief,

must be produced before the proper officers to whom the application

is made. A person who desires to defend as a pauper must

enter an appearance to a writ in the ordinary way and afterwards

apply for an order to defend as a pauper. Where a person is

admitted to sue or defend as a pauper, counsel and solicitor may

be assigned to him, and such counsel and solicitor are not at

liberty to refuse assistance unless there is some

good reason for refusing. If any person

admitted to sue or defend as a pauper agrees

to pay fees to any person for the conduct of

his business he will be dispaupered. Costs

ordered to be paid to a pauper are taxed as

in other cases. Appeals to the House of

Lords in formâ pauperis were regulated by the

Appeal (Formâ Pauperis) Act 1893, which

gave the House of Lords power to refuse a

petition for leave to sue.

INFORMATION (from Lat. informare, to

give shape or form to, to represent, describe),

the communication of knowledge; in English law, a proceeding on behalf of the crown

against a subject otherwise than by indictment.

A criminal information is a proceeding

in the King’s bench by the attorney-general

without the intervention of a grand jury.

The attorney-general, or, in his absence, the

solicitor-general, has a right ex officio to file

a criminal information in respect of any indictments,

but not for treason, felonies or

misprision of treason. It is, however, seldom

exercised, except in cases which might be

described as “enormous misdemeanours,”

such as those peculiarly tending to disturb

or endanger the king’s government, e.g. seditions,

obstructing the king’s officers in the

execution of their duties, &c. In the form of

the proceedings the attorney-general is said

to “come into the court of our lord the king before the king

himself at Westminster, and gives the court there to understand

and be informed that, &c.” Then follows the statement

of the offence as in an indictment. The information is filed in

the crown office without the leave of the court. An information

may also be filed at the instance of a private prosecutor for

misdemeanours not affecting the government, but being peculiarly

flagrant and pernicious. Thus criminal informations have been

granted for bribing or attempting to bribe public functionaries,

and for aggravated libels on public or private persons. Leave

to file an information is obtained after an application to show

cause, founded on a sworn statement of the material facts of

the case.

Certain suits might also be filed in Chancery by way of information in the name of the attorney-general, but this species of information was superseded by Order 1, rule 1 of the Rules of the Supreme Court, 1883, under which they are instituted in the ordinary way. Informations in the Court of Exchequer in revenue cases, also filed by the attorney-general, are still resorted to (see A.-G. v. Williamson, 1889, 60 L.T. 930).

INFORMER, in a general sense, one who communicates

information. The term is applied to a person who prosecutes

in any of the courts of law those who break any law or penal

statute. Such a person is called a common informer when he

furnishes evidence on criminal trials or prosecutes for breaches

of penal laws solely for the purpose of obtaining the penalty

recovered, or a share of it. An action by a common informer