JEWELRY (O. Fr. jouel, Fr. joyau, perhaps from joie, joy; Lat. gaudium; retranslated into Low Lat. jocale, a toy, from jocus, by misapprehension of the origin of the word), a collective term for jewels, or the art connected with them—jewels being personal ornaments, usually made of gems, precious stones, &c., with a setting of precious metal; in a restricted sense it is also common to speak of a gem-stone itself as a jewel, when utilized in this way. Personal ornaments appear to have been among the very first objects on which the invention and ingenuity of man were exercised; and there is no record of any people so rude as not to employ some kind of personal decoration. Natural objects, such as small shells, dried berries, small perforated stones, feathers of variegated colours, were combined by stringing or tying together to ornament the head, neck, arms and legs, the fingers, and even the toes, whilst the cartilages of the nose and ears were frequently perforated for the more ready suspension of suitable ornaments.

Amongst modern Oriental nations we find almost every kind of personal decoration, from the simple caste mark on the forehead of the Hindu to the gorgeous examples of beaten gold and silver work of the various cities and provinces of India. Nor are such decorations mere ornaments without use or meaning. The hook with its corresponding perforation or eye, the clasp, the buckle, the button, grew step by step into a special ornament, according to the rank, means, taste and wants of the wearer, or became an evidence of the dignity of office. Nor was the jewel deemed to have served its purpose with the death of its owner, for it is to the tombs of ancient peoples that we must look for evidence of the early existence of the jeweller’s art.

The jewelry of the ancient Egyptians has been preserved for us in their tombs, sometimes in, and sometimes near the sarcophagi which contained the embalmed bodies of the wearers. An amazing series of finds of the intact jewels of five princesses of the XIIth Dynasty (c. 2400 B.C.) was the result of the excavations of J. de Morgan at Dāhshur in 1894–1895. The treasure of Princess Hathor-Set contained jewels with the names of Senwosri (Usertesen) II. and III., one of whom was probably her father. The treasure of Princess Merit contained the names of the same two monarchs, and also that of Amenemhē III., to whose family Princess Nebhotp may have belonged. The two remaining princesses were Ita and Khnumit.

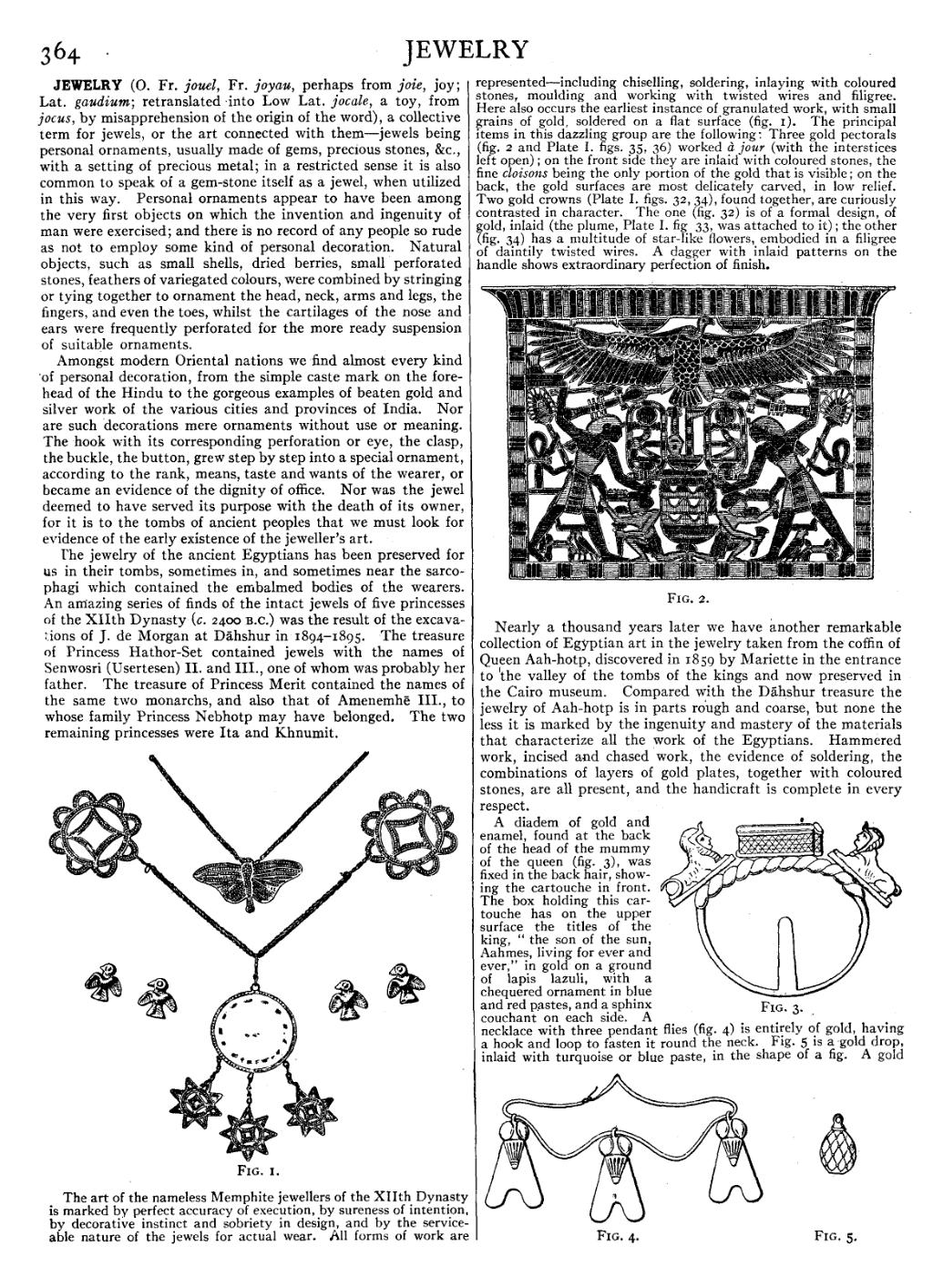

The art of the nameless Memphite jewellers of the XIIth Dynasty is marked by perfect accuracy of execution, by sureness of intention, by decorative instinct and sobriety in design, and by the serviceable nature of the jewels for actual wear. All forms of work are represented—including chiselling, soldering, inlaying with coloured stones, moulding and working with twisted wires and filigree. Here also occurs the earliest instance of granulated work, with small grains of gold, soldered on a flat surface (fig. 1). The principal items in this dazzling group are the following: Three gold pectorals (fig. 2 and Plate I. figs. 35, 36) worked à jour (with the interstices left open); on the front side they are inlaid with coloured stones, the fine cloisons being the only portion of the gold that is visible; on the back, the gold surfaces are most delicately carved, in low relief. Two gold crowns (Plate I. figs. 32, 34), found together, are curiously contrasted in character. The one (fig. 32) is of a formal design, of gold, inlaid (the plume, Plate I. fig 33, was attached to it); the other (fig. 34) has a multitude of star-like flowers, embodied in a filigree of daintily twisted wires. A dagger with inlaid patterns on the handle shows extraordinary perfection of finish.

Nearly a thousand years later we have another remarkable collection of Egyptian art in the jewelry taken from the coffin of Queen Aah-hotp, discovered in 1859 by Mariette in the entrance to the valley of the tombs of the kings and now preserved in the Cairo museum. Compared with the Dāhshur treasure the jewelry of Aah-hotp is in parts rough and coarse, but none the less it is marked by the ingenuity and mastery of the materials that characterize all the work of the Egyptians. Hammered work, incised and chased work, the evidence of soldering, the combinations of layers of gold plates, together with coloured stones, are all present, and the handicraft is complete in every respect.

|

|

| ||

| Fig. 3. | Fig. 4. |

Fig. 5. |

A diadem of gold and enamel, found at the back of the head of the mummy of the queen (fig. 3), was fixed in the back hair, showing the cartouche in front. The box holding this cartouche has on the upper surface the titles of the king, “the son of the sun, Aahmes, living for ever and ever,” in gold on a ground of lapis lazuli, with a chequered ornament in blue and red pastes, and a sphinx couchant on each side. A necklace with three pendant flies (fig. 4) is entirely of gold, having a hook and loop to fasten it round the neck. Fig. 5 is a gold drop, inlaid with turquoise or blue paste, in the shape of a fig. A gold