the raw material of a large and important industry throughout

the regions of Eastern Bengal. The Hindu population made the

material up into cordage, paper and cloth, the chief use of the

latter being in the manufacture of gunny bags. Indeed, up to

1830–1840 there was little or no competition with hand labour for

this class of material. The process of weaving gunnies for bags

and other coarse articles by these hand-loom weavers has been

described as follows:—

“Seven sticks or chattee weaving-posts, called tanā parā or warp, are fixed upon the ground, occupying the length equal to the measure of the piece to be woven, and a sufficient number of twine or thread is wound on them as warp called tanā. The warp is taken up and removed to the weaving machine. Two pieces of wood are placed at two ends, which are tied to the ohari and okher or roller; they are made fast to the khoti. The belut or treadle is put into the warp; next to that is the sarsul; a thin piece of wood is laid upon the warp, called chupari or regulator. There is no sley used in this, nor is a shuttle necessary; in the room of the latter a stick covered with thread called singa is thrown into the warp as woof, which is beaten in by a piece of plank called beyno, and as the cloth is woven it is wound up to the roller. Next to this is a piece of wood called khetone, which is used for smoothing and regulating the woof; a stick is fastened to the warp to keep the woof straight.”

Gunny cloth is woven of numerous qualities, according to the purpose to which it is devoted. Some kinds are made close and dense in texture, for carrying such seed as poppy or rape and sugar; others less close are used for rice, pulses, and seeds of like size, and coarser and opener kinds again are woven for the outer cover of packages and for the sails of country boats. There is a thin close-woven cloth made and used as garments among the females of the aboriginal tribes near the foot of the Himalayas, and in various localities a cloth of pure jute or of jute mixed with cotton is used as a sheet to sleep on, as well as for wearing purposes. To indicate the variety of uses to which jute is applied, the following quotation may be cited from the official report of Hem Chunder Kerr as applying to Midnapur.

“The articles manufactured from jute are principally (1) gunny bags; (2) string, rope and cord; (3) kampa, a net-like bag for carrying wood or hay on bullocks; (4) chat, a strip of stuff for tying bales of cotton or cloth; (5) dola, a swing on which infants are rocked to sleep; (6) shika, a kind of hanging shelf for little earthen pots, &c.; (7) dulina, a floor-cloth; (8) beera, a small circular stand for wooden plates used particularly in poojahs; (9) painter’s brush and brush for white-washing; (10) ghunsi, a waist-band worn next to the skin; (11) gochh-dari, a hair-band worn by women; (12) mukbar, a net bag used as muzzle for cattle; (13) parchula, false hair worn by players; (14) rakhi-bandhan, a slender arm-band worn at the Rakhi-poornima festival; and (15) dhup, small incense sticks burned at poojahs.”

The fibre began to receive attention in Great Britain towards the close of the 18th century, and early in the 19th century it was spun into yarn and woven into cloth in the town of Abingdon. It is claimed that this was the first British town to manufacture the material. For years small quantities of jute were imported into Great Britain and other European countries and into America, but it was not until the year 1832 that the fibre may be said to have made any great impression in Great Britain. The first really practical experiments with the fibre were made in this year in Chapelshade Works, Dundee, and these experiments proved to be the foundation of an enormous industry. It is interesting to note that the site of Chapelshade Works was in 1907 cleared for the erection of a large new technical college.

In common with practically all new industries progress was slow for a time, but once the value of the fibre and the cloth produced from it had become known the development was more rapid. The pioneers of the work were confronted with many difficulties; most people condemned the fibre and the cloth, many warps were discarded as unfit for weaving, and any attempt to mix the fibre with flax, tow or hemp was considered a form of deception. The real cause of most of these objections was the fact that suitable machinery and methods of treatment had not been developed for preparing yarns from this useful fibre. Warden in his Linen Trade says:—

“For years after its introduction the principal spinners refused to have anything to do with jute, and cloth made of it long retained a tainted reputation. Indeed, it was not until Mr. Rowan got the Dutch government, about 1838, to substitute jute yarns for those made from flax in the manufacture of the coffee bagging for their East Indian possessions, that the jute trade in Dundee got a proper start. That fortunate circumstance gave an impulse to the spinning of the fibre which it never lost, and since that period its progress has been truly astonishing.”

The demand for this class of bagging, which is made from fine hessian yarns, is still great. These fine Rio hessian yarns form an important branch of the Dundee trade, and in some weeks during 1906 as many as 1000 bales were despatched to Brazil, besides numerous quantities to other parts of the world.

For many years Great Britain was the only European country engaged in the manufacture of jute, the great seat being Dundee. Gradually, however, the trade began to extend, and now almost every European country is partly engaged in the trade.

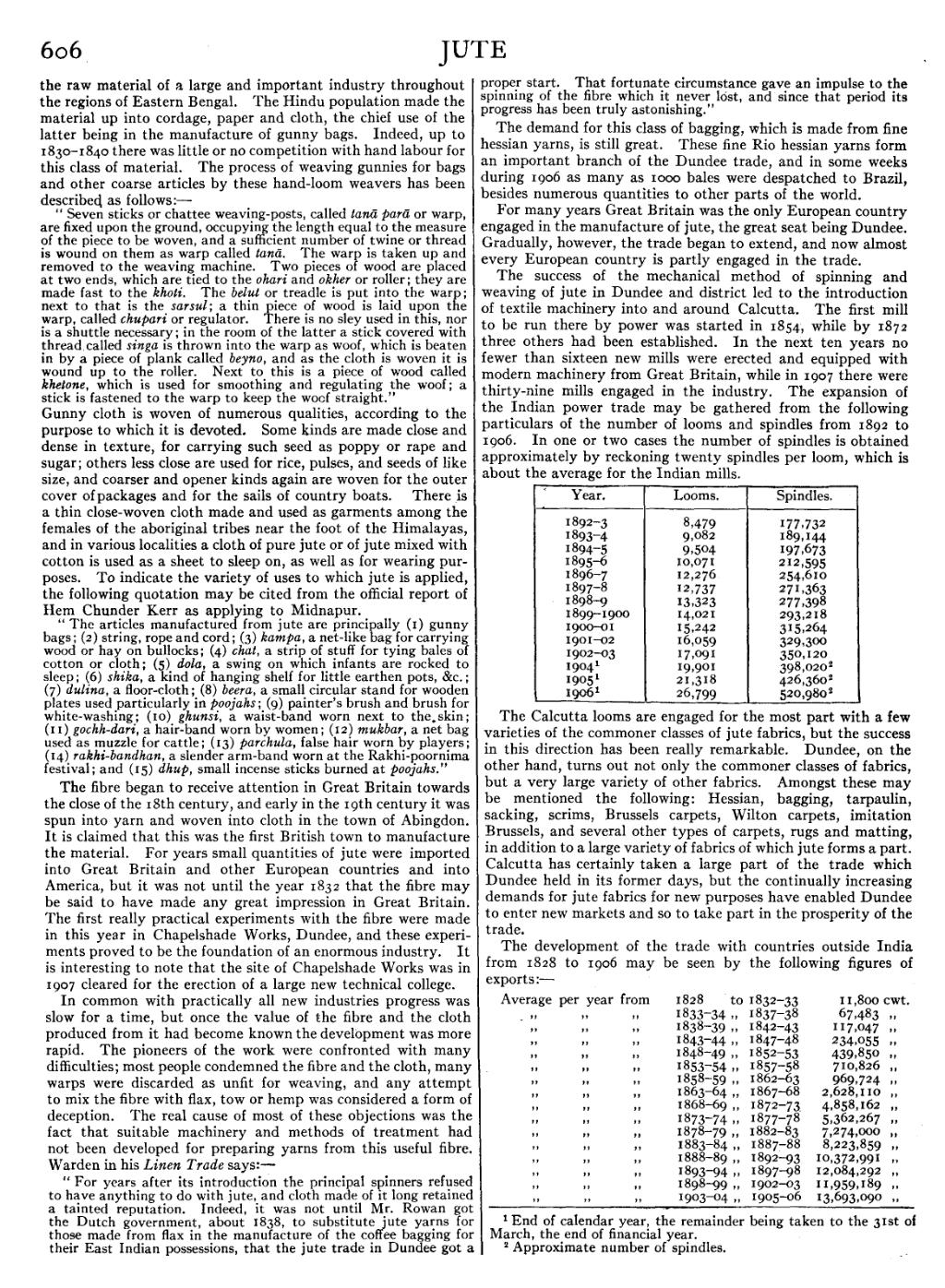

The success of the mechanical method of spinning and weaving of jute in Dundee and district led to the introduction of textile machinery into and around Calcutta. The first mill to be run there by power was started in 1854, while by 1872 three others had been established. In the next ten years no fewer than sixteen new mills were erected and equipped with modern machinery from Great Britain, while in 1907 there were thirty-nine mills engaged in the industry. The expansion of the Indian power trade may be gathered from the following particulars of the number of looms and spindles from 1892 to 1906. In one or two cases the number of spindles is obtained approximately by reckoning twenty spindles per loom, which is about the average for the Indian mills.

| Year. | Looms. | Spindles. |

| 1892–3 | 8,479 | 177,732 |

| 1893–4 | 9,082 | 189,144 |

| 1894–5 | 9,504 | 197,673 |

| 1895–6 | 10,071 | 212,595 |

| 1896–7 | 12,276 | 254,610 |

| 1897–8 | 12,737 | 271,363 |

| 1898–9 | 13,323 | 277,398 |

| 1899–1900 | 14,021 | 293,218 |

| 1900–01 | 15,242 | 315,264 |

| 1901–02 | 16,059 | 329,300 |

| 1902–03 | 17,091 | 350,120 |

| 1904* | 19,901 | 398,020** |

| 1905* | 21,318 | 426,360** |

| 1906* | 26,799 | 520,980** |

* End of calendar year, the remainder being taken

to the 31st of March, the end of financial year.

** Approximate number of spindles.

The Calcutta looms are engaged for the most part with a few varieties of the commoner classes of jute fabrics, but the success in this direction has been really remarkable. Dundee, on the other hand, turns out not only the commoner classes of fabrics, but a very large variety of other fabrics. Amongst these may be mentioned the following: Hessian, bagging, tarpaulin, sacking, scrims, Brussels carpets, Wilton carpets, imitation Brussels, and several other types of carpets, rugs and matting, in addition to a large variety of fabrics of which jute forms a part. Calcutta has certainly taken a large part of the trade which Dundee held in its former days, but the continually increasing demands for jute fabrics for new purposes have enabled Dundee to enter new markets and so to take part in the prosperity of the trade.

The development of the trade with countries outside India from 1828 to 1906 may be seen by the following figures of exports:—

| Average | per year | from | 1828 | to | 1832–33 | 11,800 | cwt. |

| ” | ” | ” | 1833–34 | ” | 1837–38 | 67,483 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1838–39 | ” | 1842–43 | 117,047 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1843–44 | ” | 1847–48 | 234,055 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1848–49 | ” | 1852–53 | 439,850 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1853–54 | ” | 1857–58 | 710,826 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1858–59 | ” | 1862–63 | 969,724 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1863–64 | ” | 1867–68 | 2,628,110 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1868–69 | ” | 1872–73 | 4,858,162 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1873–74 | ” | 1877–78 | 5,362,267 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1878–79 | ” | 1882–83 | 7,274,000 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1883–84 | ” | 1887–88 | 8,223,859 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1888–89 | ” | 1892–93 | 10,372,991 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1893–94 | ” | 1897–98 | 12,084,292 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1898–99 | ” | 1902–03 | 11,959,189 | ” |

| ” | ” | ” | 1903–04 | ” | 1905–06 | 13,693,090 | ” |