A. J. Evans in Journal of Hellenic Studies; on the subject generally,

articles in Roscher’s Lexikon der Mythologie and Daremberg and

Saglio’s Dictionnaire des antiquités.

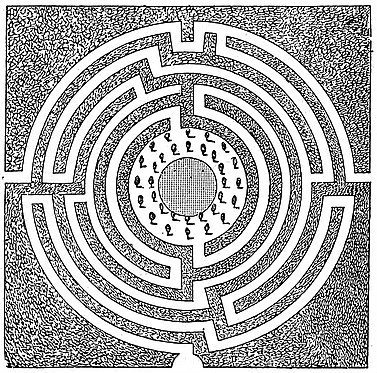

Fig. 2.—Labyrinth of Batty Langley.

Fig. 3.—Labyrinth at Versailles.

In gardening, a labyrinth or maze means an intricate network of pathways enclosed by hedges or plantations, so that those who enter become bewildered in their efforts to find the centre or make their exit. It is a remnant of the old geometrical style of gardening. There are two methods of forming it. That which is perhaps the more common consists of walks, or alleys as they were formerly called, laid out and kept to an equal width or nearly so by parallel hedges, which should be so close and thick that the eye cannot readily penetrate them. The task is to get to the centre, which is often raised, and generally contains a covered seat, a fountain, a statue or even a small group of trees. After reaching this point the next thing is to return to the entrance, when it is found that egress is as difficult as ingress. To every design of this sort there should be a key, but even those who know the key are apt to be perplexed. Sometimes the design consists of alleys only, as in fig. 1, published in 1706 by London and Wise. In such a case, when the farther end is reached, there only remains to travel back again. Of a more pretentious character was a design published by Switzer in 1742. This is of octagonal form, with very numerous parallel hedges and paths, and “six different entrances, whereof there is but one that leads to the centre, and that is attended with some difficulties and a great many stops.” Some of the older designs for labyrinths, however, avoid this close parallelism of the alleys, which, though equally involved and intricate in their windings, are carried through blocks of thick planting, as shown in fig. 2, from a design published in 1728 by Batty Langley. These blocks of shrubbery have been called wildernesses. To this latter class belongs the celebrated labyrinth at Versailles (fig. 3), of which Switzer observes, that it “is allowed by all to be the noblest of its kind in the world.”

Fig. 4.—Maze at Hampton Court.

Fig. 5.—Maze at Somerleyton Hall.

Whatever style be adopted, it is essential that there should be a thick healthy growth of the hedges or shrubberies that confine the wanderer. The trees used should be impenetrable to the eye, and so tall that no one can look over them; and the paths should be of gravel and well kept. The trees chiefly used for the hedges, and the best for the purpose, are the hornbeam among deciduous trees, or the yew among evergreens. The beech might be used instead of the hornbeam on suitable soil. The green holly might be planted as an evergreen with very good results, and so might the American arbor vitae if the natural soil presented no obstacle. The ground must be well prepared, so as to give the trees a good start, and a mulching of manure during the early years of their growth would be of much advantage. They must be kept trimmed in or clipped, especially in their earlier stages; trimming with the knife is much to be preferred to clipping with shears. Any plants getting much in advance of the rest should be topped, and the whole kept to some 4 ft. or 5 ft. in height until the lower parts are well thickened, when it may be allowed to acquire the allotted height by moderate annual increments. In cutting, the hedge (as indeed all hedges) should be