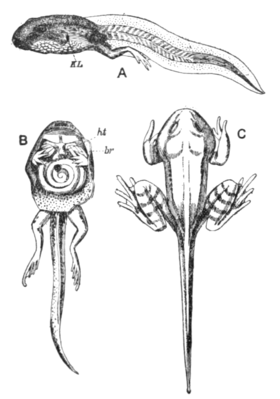

In the frog (fig. 1) the structural changes which obtain full fruition at the metamorphosis take place gradually during the previous tadpole life. They relate mainly to the alterations of the respiratory organs and vascular system which are required for the purely terrestrial life of the frog, and to the appearance of the paired limbs.

The changes in the respiratory and vascular organs are led up to in the tadpole, which during the greater part of its aquatic life is a truly amphibious animal, breathing by lungs as well as by gills; but a sudden change occurs in these organs at the metamorphosis. The limbs which were slowly formed during tadpole life—the posterior pair visibly, the anterior under cover of the operculum (fig. 1, B)—are of no use to the tadpole and must constitute a pure burden to it. The principal events of the metamorphosis are the sudden appearance of the anterior limbs, and the complete closure of the gill aperture (fig. 1, C). The appearance of the anterior limbs and the acquisition of functional importance by both pairs enable the frog to leave the water and pass on to the land to lead its terrestrial Life. The other larval organs, such as the gills and the tail, gradually shrink in size and ultimately vanish. In the case of the gills this shrinkage had begun before the metamorphosis, but the tail shows no sign of diminution until the frog is ready to pass on to the land.

The distinguishing feature of this type of metamorphosis is that the animal is burdened for a certain period, both before and after, with organs which are useless to it. In the next type, which is exemplified by the metabolous Insecta, this occurs to a much smaller extent, although the changes of habitat and the corresponding changes of structure are more remarkable. In insecta the change is usually from a terrestrial or aquatic habitat to an aerial one. The larva of a butterfly is a worm-like organism which creeps on and voraciously devours the foliage of certain plants (fig. 2, C). During its life it undergoes much growth, but no important change in structure. When it leaves the egg it is adapted to live and feed on a particular species of plant, on or near which the eggs are deposited by the parent butterfly. It has powerful biting jaws by which it procures its vegetable food. The adult, on the other hand, is a winged creature which also lives on plants but in quite a different way to the larva (fig. 2, A). It flies from plant to plant and obtains its food by sucking the juices of flowers and other parts. The powerful mandibles of the larva have disappeared and in their place we find a suctorial proboscis formed by the first maxillae [fig. 2, A (4)].

Between the larva and the adult insect there is interposed a resting stage, the so-called pupa (fig. 2, B), during which no food is taken, but very important changes of structure occur. These changes consist of two processes: (1) histolysis, by which most of the larval organs are destroyed by the action of phagocytes; and (2) histogenesis, by which the corresponding organs of the imago are developed from the imaginal disks. The imaginal disks appear to arise in the embryo in which they develop, some of them from the epiblast and some from the hypoblast. They persist practically unchanged through larval life and become active as centres of growth in the pupa. The pupal stage in such a metamorphosis may be compared to a second embryonic stage in which the organs of the adult assume their final shape. In this kind of metamorphosis the larval organs are entirely got rid of in the pupal stage, during which the insect is as a rule incapable of locomotion and takes no food; and the new formation of organs—especially those of locomotion and alimentation—which is necessitated by the totally different habits of the larva and mature insect, is also accomplished at the same period, largely, no doubt, at the expense of the material afforded by the disrupted larval, organs. The larva itself does not form any of these organs and carry them about during its active life, though it does possess the very minute centres of growth known as the imaginal disks which burst into activity after the larval life is over. It must not be supposed that in all insects in which the sexual animal has a different habitat from the young form, there is a metamorphosis of the kind just described. In the may-flies and dragon-flies, in which the larva is aquatic, the change is prepared for some time before the actual metamorphosis, the organs which are necessary for the aerial existence being gradually acquired during larval life. In such cases, the metamorphosis belongs to our first type and consists of the act by which the organs previously and gradually acquired suddenly become functional. We have now considered in detail two typical cases of metamorphosis. In the first the change is gradually led up to and the larva is burdened, in its later stages at least, with organs which are of no use to it and only become functional at the metamorphosis. In the other, the change is not led up to. It is sudden, and a kind of second embryonic period is established