curve to be rectified. This was accomplished in 1657 by Neil in England, and in 1659 by Heinrich van Haureat in Holland. Newton showed that all the five varieties of the diverging parabolas may be exhibited as plane sections of the solid of revolution of the semi-cubical parabola. A plane oblique to the axis and passing below the vertex gives the first variety; if it passes through the vertex,

the second form; if above the vertex and oblique or parallel to the axis, the third form; if below the vertex and touching the surface, the fourth form, and if the plane contains the axis, the fifth form results (see Curve).

|

|

| Fig. 6. | Fig. 7. |

|

|

| ||

| Fig. 8. | Fig. 9. | Fig. 10. |

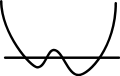

The biquadratic parabola has, in its most general form, the equation , and consists of a serpentinous and two parabolic branches (fig. 8).If all the roots of the quartic in x are equal the curve assumes the form shown in fig. 9, the axis of x being a double tangent. If the two middle roots are equal, fig. 10 results. Other forms which correspond to other relations between the roots can be readily deduced from the most general form. (See Curve; and Geometry, Analytical.)

PARACELSUS (c. 1490–1541), the famous German physician of the 16th century, was probably born near Einsiedeln, in the canton Schwyz, in 1490 or 1491 according to some, or 1493 according to others. His father, the natural son of a grandmaster of the Teutonic order, was Wilhelm Bombast von Hohenheim, who had a hard struggle to make a subsistence as a physician. His mother was superintendent of the hospital at Einsiedeln, a post she relinquished upon her marriage. Paracelsus’s name was Theophrastus Bombast von Hohenheim; for the names Philippus and Aureolus which are sometimes added good authority is wanting, and the epithet Paracelsus, like some similar compounds, was probably one of his own making, and was meant to denote his superiority to Celsus.

Of the early years of Paracelsus’s life hardly anything is known. His father was his first teacher, and took pains to instruct him in all the learning of the time, especially in medicine. Doubtless Paracelsus learned rapidly what was put before him, but he seems at a comparatively early age to have questioned the value of what he was expected to acquire, and to have soon struck out ways for himself. At the age of sixteen he entered the university of Basel, but probably soon abandoned the studies therein pursued. He next went to J. Trithemius, the abbot of Sponheim and afterwards of Würzburg, under whom he prosecuted chemical researches. Trithemius is the reputed author of some obscure tracts on the great elixir, and as there was no other chemistry going Paracelsus would have to devote himself to the reiterated operations so characteristic of the notions of that time. But the confection of the stone of the philosophers was too remote a possibility to gratify the fiery spirit of a youth like Paracelsus, eager to make what he knew, or could learn, at once available for practical medicine. So he left school chemistry as he had forsaken university culture, and started for the mines in Tirol owned by the wealthy family of the Fuggers. The sort of knowledge he got there pleased him much more. There at least he was in contact with reality. The struggle with nature before the precious metals could be made of use impressed upon him more and more the importance of actual personal observation. He saw all the mechanical difficulties that had to be overcome in mining; he learned the nature and succession of rocks, the physical properties of minerals, ores and metals; he got a notion of mineral waters; he was an eyewitness of the accidents which befell the miners, and studied the diseases which attacked them; he had proof that positive knowledge of nature was not to be got in schools and universities, but only by going to nature herself, and to those who were constantly engaged with her. Hence came Paracelsus’s peculiar mode of study. He attached no value to mere scholarship; scholastic disputations he utterly ignored and despised—and especially the discussions on medical topics, which turned more upon theories and definitions than upon actual practice. He therefore went wandering over a great part of Europe to learn all that he could. In so doing he was one of the first physicians of modern times to profit by a mode of study which is now reckoned indispensable. The book of nature, he affirmed, is that which the physician must read, and to do so he must walk over the leaves. The humours and passions and diseases of different nations are different, and the physician must go among the nations if he will be master of his art; the more he knows of other nations, the better he will understand his own. And the commentary of his own and succeeding centuries upon these very extreme views is that Paracelsus was no scholar, but an ignorant vagabond. He himself, however, valued his method and his knowledge very differently, and argued that he knew what his predecessors were ignorant of, because he had been taught in no human school. “Whence have I all my secrets, out of what writers and authors? Ask rather how the beasts have learned their arts. If nature can instruct irrational animals, can it not much more men?” In this new school discovered by Paracelsus, and since attended with the happiest results by many others, he remained for about ten years. He had acquired great stores of facts, which it was impossible for him to have reduced to order, but which gave him an unquestionable superiority to his contemporaries. So in 1526 or 1527, on his return to Basel, he was appointed town physician, and shortly afterwards he gave a course of lectures on medicine in the university. Unfortunately for him, the lectures broke away from tradition. They were in German, not in Latin; they were expositions of his own experience, of his own views, of his own methods of curing, adapted to the diseases that afflicted the Germans in the year 1527, and they were not commentaries on the text of Galen or Avicenna. They attacked, not only these great authorities, but the German graduates who followed them and disputed about them in 1527. They criticized in no measured terms the current medicine of the time, and exposed the practical ignorance, the pomposity, and the greed of those who practised it.

The truth of Paracelsus’s doctrines was apparently confirmed by his success in curing or mitigating diseases for which the regular physicians could do nothing. For about a couple of years his reputation and practice increased to a surprising extent. But at the end of that time people began to recover themselves. Paracelsus had burst upon the schools with such novel views and methods, with such irresistible criticism, that all opposition was at first crushed flat. Gradually the sea began to rise. His enemies watched for slips and failures; the physicians maintained that he had no degree, and insisted that he should give proof of his qualifications. Moreover, he had a pharmaceutical system of his own which did not harmonize with the commercial arrangements of the apothecaries, and he not only did not use up their drugs like the Galenists, but, in the exercise of his functions as town physician, he urged the authorities to keep a sharp eye on the purity of their wares, upon their knowledge of their art, and upon their transactions with their friends the physicians. The growing jealousy and enmity culminated in a dispute with Canon Cornelius von Lichtenfels, who, having called in Paracelsus after other physicians had given up his case, refused to pay the fee he had promised in the event of cure; and, as the judges, to their discredit, sided with the canon, Paracelsus had no alternative but to tell them his opinion of the whole case and of their notions of justice. So little doubt left he on the subject that his friends judged it prudent for him to leave Basel at once, as it had been resolved to punish him for the attack on the authorities of which he had been guilty. He departed in such haste that he carried nothing with him, and some chemical apparatus and other property were taken charge of by J. Oporinus (1507–1568), his pupil and amanuensis. He went first to Esslingen, where he remained for a brief period, but had soon to leave from absolute want. Then began his wandering life, the course of which can be traced by the dates of his