regulated by the shape and width of the share, working in combination with a proper shaped breast. A “crested” furrow is obtained by the use of a share, the wing of which is set at a higher altitude than the point, but this type of furrow is less generally found than the “ rectangular ” form obtained by a level-edged share, which leaves a flat bottom.

Wide Broken Furrow.

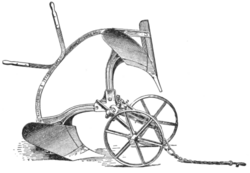

Digging Plough.

During the greater part of the 19th century the ideal of ploughing was to preserve the furrow-slice unbroken, and this object was attained by the use of long mould-boards which turned the slices gently and gradually, laying them over against one another at an angle of 45°, thus providing drainage at the bottom of the furrow, and exposing the greatest possible surface to the influences of the weather. Subsequently the digging plough came into vogue; the share being wider, a wider furrow is cut, while the slice is inverted by a short concave mould-board with a sharp turn which at the same time breaks up and pulverizes the soil after the fashion of a spade. Except on extremely heavy soils or on shallow soils with a subsoil which it is unwise to bring upon the surface, the modern tendency is in favour of the digging plough.

A ploughed field is divided into lands or sections of equal width separated by furrows. On light easy draining land 22 yds. is the usual width; on the heaviest lands it may be as little as 5 yds., and in the latter case the furrows will act as drains into which the water flows from the intervening ridges.[1]

Turnwrest Plough.

Certain important variations of the ordinary plough demand consideration. The one-way plough lays the furrows alternately to its left and right, so that they all slope in the same direction. This is found advantageous on hill-sides where the work is easier if all the furrows are turned downhill; or from another point of view the furrows may be all laid uphill so as to counteract the tendency for the soil to work down the slope. One-way ploughs also leave the land level and dispense with the wide open furrows between the ridges which are left by the ordinary plough. They are made on different principles. One type comprises two separate ploughs, one right hand and one left, which revolve on the beam, one working, while the other stands vertically above it. In another the mould board and share are shaped so that they can be swung on a swivel under the beam when the latter is lifted. A third type is made on the “ balance ” principle, two plough beams with mould-boards being placed at right angles to one another, so that while the right-hand plough is at work the left-hand is elevated above the ground.

Balance Plough.

Double-furrow or multiple ploughs are a combination of two or more ploughs arranged in echelon so as to plough two or more furrows. The weight of these implements necessitates some provision for turning them at the headlands, and this is supplied either by a bowl wheel, enabling the plough to be turned on one side, or by a pair of wheels cranked so that they can be raised by a lever when the plough is working. The double-furrow plough was known as early as the 17th century, but, till the introduction of the latter device by Ransome in 1873, cannot be said to have been in successful use.

Riding Plough.

The “sulky” or riding plough is little known in the United Kingdom, but on the larger arable tracts of other countries where quick work is essential and the character of the surface permits, it is in general use. In this form of plough the frame is mounted on three wheels, one of which runs on the land, and the other two in the furrow. The furrow wheels are placed on inclined axles, the plough beam being carried on swing links, operated by a hand lever when it is necessary to raise the plough out of the furrow. The land wheel and the forward furrow wheel are adjustable vertically with reference to the frame, for the purpose of controlling the action of the plough.

In the disk plough, which is built both as a riding and a walking plough, the essential feature is the substitution of a concavo-

- ↑ Methods of the “setting-out” of land to be ploughed together with a full discussion of other technical details relating to ploughing will be found in ch. vii. of W. J. Malden's Workman’s Technical Instructor (London, 1905).