theory that the bonds represented the cost of the enterprise, and the stock the prospective profits. As a natural result weak railway companies in the United States have frequently been declared insolvent by the courts, owing to their inability in periods of commercial depression to meet their acknowledged obligations, and in the reorganization which has followed the shareholders have usually had to accept a loss, temporary or permanent.

The situation in Great Britain has been wholly different. The debt in that country is relatively small in amount, and is not represented by securities based upon hypothecation of the company’s real property, as with the American railway bond, resting on a first, second or third mortgage. But British share capital has been issued so freely for extension and improvement work of all sorts, including the costly requirements of the Board of Trade, that a situation has been reached where the return on the outstanding securities tends to diminish year by year. Although this fact will not in itself make the companies liable to any process of reorganization similar to that following insolvency and foreclosure of the American railway, it is probable that reorganization of some sort must nevertheless take place in Great Britain, and it may well be questioned whether the position of the transportation system of that country would not have been better if it had been built up and projected on the experience gained by actual earlier losses, as in the United States.

Thus the characteristic defect in the British railway organization has been the tendency to put out new capital at a rate faster than has been warranted by the annual increases in earnings. The American railways do not have to face this situation; but, after a long term of years, when they were allowed to do much as they pleased, they have now been brought sharply to book by almost every form of constituted authority to be found in the states, and they are suffering from increased taxation, from direct service requirements, and from a general tendency on the part of regulating authorities to reduce rates and to make it impossible to increase them. Meantime, the purchasing power of the dollar which the railway company receives for a specified service is gradually growing smaller, owing to the general increases year by year in wages and in the cost of material. The railways are prospering because they are managed with great skill and are doing increasing amounts of business, though at lessening unit profits. But there is danger of their reaching the point where there is little or no margin between unit costs of service and unit receipts for the service. It will probably be inevitable for American railway rates to trend somewhat upward in the future, as they have gradually declined in the past; but the process apparently cannot be accomplished without considerable friction with the governing authorities. The attitude of the courts is not that the railways should work without compensation, but that the compensation should not exceed a fair return on funds actually expended by the railway. This is in line with the provisions in the Constitution of the United States regarding the protection of property, but the difficulty in applying the principle to the railway situation lies in the fact that costs have to be met by averaging the returns on the total amount of business done, and it is often impossible, in specific instances, to secure a rate which can be considered to yield a fair return on the specific service rendered. Hence losses in one quarter must be compensated by gains in another—a process which the law, regarding only the gains, renders very difficult.

The growth of railways has been accompanied by a world-wide tendency toward the consolidation of small independent ventures into large groups of lines able to aid one another in the exchange of traffic and to effect economics in administration and in the purchase of supplies. Both in England and in America this process of consolidation has been obstructed by all known legislative devices, because of the widespread belief that competition in the field of transportation was necessary if fair prices were to be charged for the service. But the general tendency to regulate rates by authority of the state has apparently rendered unnecessary the old plan of rate regulation through competition, even if it had not been demonstrated often and again that this form of regulation is costly for all concerned and is effective only during rare periods of direct conflict between companies. Nevertheless, in spite of difficulties, consolidation has gone on with great rapidity. When Mr E. H. Harriman died he exercised direct authority over more than 50,000 m. of railway, and the tendency of all the great American railway systems, even when not tied to one another in common ownership, is to increase their mileage year by year by acquiring tributary lines. The smaller company exchanges its stock for stock of the larger system on an agreed basis, or sells it outright, and the bondholders of the absorbed line often have a similar opportunity to exchange their securities for obligations of the parent company, which are on a stronger basis or have a broader market. Similarly in Great Britain there is a tendency towards combination by mutual agreement among the companies while they still preserve their independent existence.

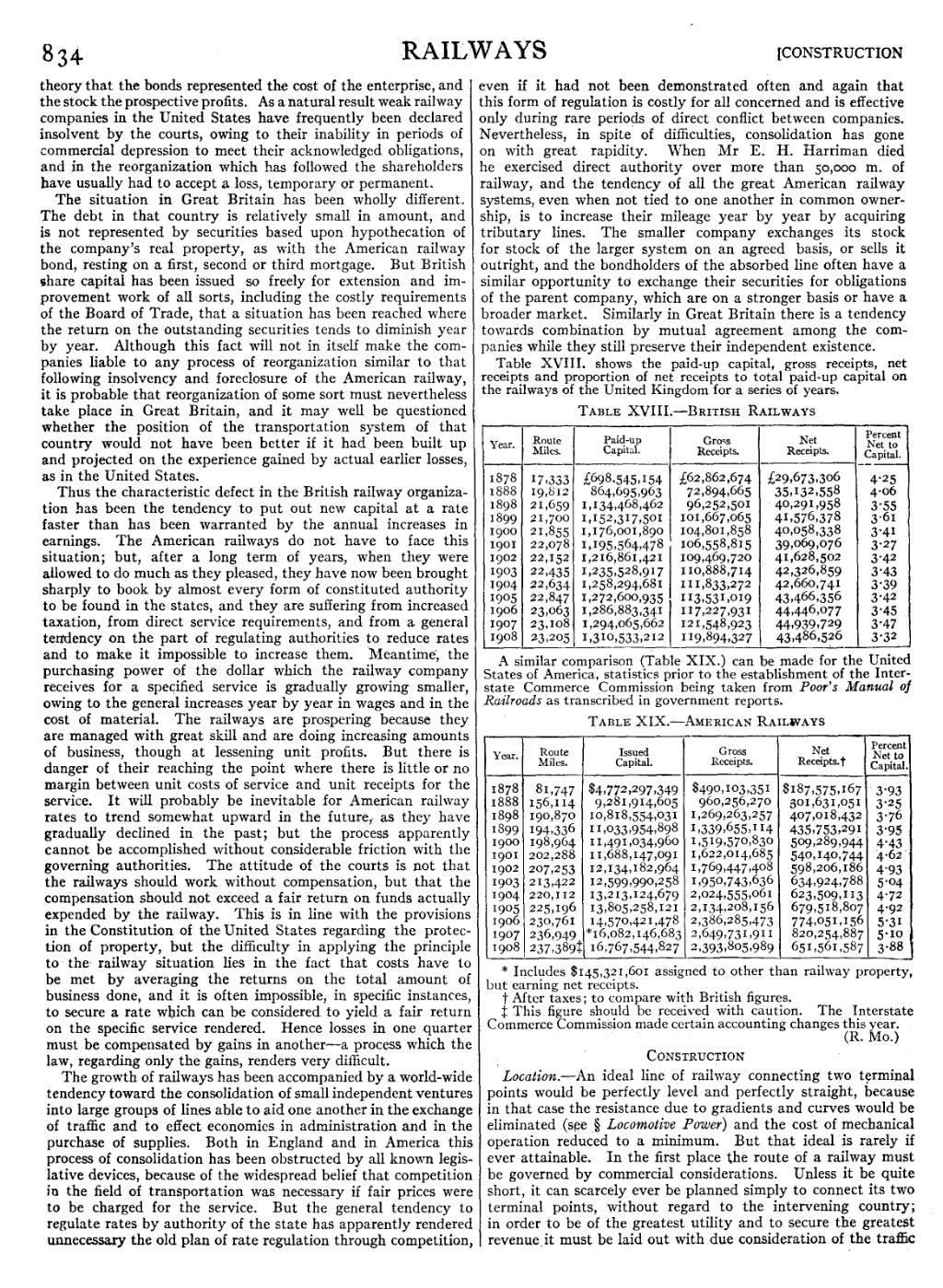

Table XVIII. shows the paid-up capital, gross receipts, net receipts and proportion of net receipts to total paid-up capital on the railways of the United Kingdom for a series of years.

| Year | Route Miles |

Paid-up Capital |

Gross Receipts |

Net Receipts |

Percent Net to Capital |

| 1878 | 17,333 | £698,545,154 | £62,862,674 | £29,673,306 | 4·25 |

| 1888 | 19,812 | 864,695,963 | 72,394,665 | 35,132,558 | 4·06 |

| 1898 | 21,659 | 1,134,468,462 | 96,252,501 | 40,291,958 | 3·55 |

| 1899 | 21,700 | 1,152,317,501 | 101,667,065 | 41,576,378 | 3·61 |

| 1900 | 21,855 | 1,176,001,890 | 104,801,858 | 40,058,338 | 3·41 |

| 1901 | 22,078 | 1,195,564,478 | 106,558,815 | 39,069,076 | 3·27 |

| 1902 | 22,152 | 1,216,861,421 | 109,469,720 | 41,628,502 | 3·42 |

| 1903 | 22,435 | 1,235,523,917 | 110,888,714 | 42,326,859 | 3·43 |

| 1904 | 22,634 | 1,258,294,681 | 111,833,272 | 42,660,741 | 3·39 |

| 1905 | 22,847 | 1,272,600,935 | 113,531,019 | 43,466,356 | 3·42 |

| 1906 | 23,063 | 1,286,883,341 | 117,227,931 | 44,446,077 | 3·45 |

| 1907 | 23,108 | 1,294,065,662 | 121,543,923 | 44,939,729 | 3·47 |

| 1908 | 23,205 | 1,310,533,212 | 119,894,327 | 43,486,526 | 3·32 |

A similar comparison (Table XIX.) can be made for the United States of America, statistics prior to the establishment of the Interstate Commerce Commission being taken from Poor’s Manual of Railroads as transcribed in government reports.

| Year | Route Miles |

Issued Capital |

Gross Receipts |

Net Receipts[1] |

Percent Net to Capital |

| 1878 | 81,747 | $4,772,297,349 | $490,103,351 | $187,575,167 | 3·93 |

| 1888 | 156,114 | 9,281,914,605 | 960,256,270 | 301,631,051 | 3·25 |

| 1898 | 190,870 | 10,818,554,031 | 1,269,263,257 | 407,018,432 | 3·76 |

| 1899 | 194,336 | 11,033,954,898 | 1,339,655,114 | 435,753,291 | 3·95 |

| 1900 | 198,964 | 11,491,034,960 | 1,519,570,830 | 509,239,944 | 4·43 |

| 1901 | 202,288 | 11,688,147,091 | 1,622,014,685 | 540,140,744 | 4·62 |

| 1902 | 207,253 | 12,134,182,964 | 1,769,447,408 | 598,206,186 | 4·93 |

| 1903 | 213,422 | 12,599,990,258 | 1,950,743,636 | 634,924,733 | 5·04 |

| 1904 | 220,112 | 13,213,124,679 | 2,024,555,061 | 623,509,113 | 4·72 |

| 1905 | 225,196 | 13,805,258,121 | 2,134,208,156 | 679,518,807 | 4·92 |

| 1906 | 230,761 | 14,570,421,473 | 2,386,235,473 | 774,051,156 | 5·31 |

| 1907 | 236,949 | [2]16,082,146,683 | 2,649,731,911 | 820,254,887 | 5·10 |

| 1908 | [3]237,339 | 16,767,544,827 | 2,393,305,939 | 651,561,537 | 3·88 |

(R. Mo.)

Construction

Location.—An ideal line of railway connecting two terminal points would be perfectly level and perfectly straight, because in that case the resistance due to gradients and curves would be eliminated (see § Locomotive Power) and the cost of mechanical operation reduced to a minimum. But that ideal is rarely if ever attainable. In the first place the route of a railway must be governed by commercial considerations. Unless it be quite short, it can scarcely ever be planned simply to connect its two terminal points, without regard to the intervening country; in Order to be of the greatest utility and to secure the greatest revenue it must be laid out with due consideration of the traffic