absolutely drill-proof receptacle. This patent is noteworthy as

being the only one connected with the lock and safe industry

which has been extended by the privy council.

It is about this period (1860–1870), perhaps the most important in the history of safes, that the opening of safes by wedges seems to have become prominent. The effect of wedges was to bend out the side of the safe sufficiently to allow of the insertion of a crowbar between the body and the edge of the door, and various devices were adopted by different makers with the object of resisting this mode of attack. These devices may be placed in three classes: (1) the fixing to the door of studs or projections which, when the door closed, passed into holes or recesses in the frame of the body; (2) the use of bolts hooking into the side framing or entering the bolt holes at an angle; (3) the strengthening of the side framing and of the attachment of the bolts to the outer door-plate. The third of these methods (fig. 2) was patented' by Samuel Chatwood in 1862, and is still very commonly employed. The second method was used by»Chubb and Chatwood, but is not today in general use. The first method was used by all makers of repute, but has now been abandoned, as the increased structural strength of the better class of safes renders such devices unnecessary.

Fig. 2.

To prevent safes from being opened by the drilling of one or two small holes in such positions as to destroy the security of the lock itself, advantage was taken of the improvements in the manufacture of high carbon steel, and even in what is to-day called the “fire-proof” safe a plate of steel which offers considerable resistance to drilling is placed between the outer door plate and the lock.

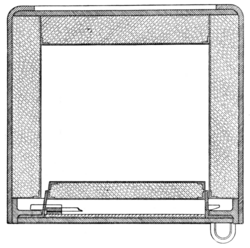

For many years little advance was made except such as consisted in substituting steel for iron and in general gaining increased strength by the utilization of better materials, although many safes are made and sold to-day which -offer little if any more resistance to Ere and thieves than those of 1860–1870. About 1888 the “solid” safe was introduced. In this the top, bottom and two sides of the safe, together with the flanges at the back only or at both back and front, are bent from a single steel plate (fig. 3). This construction, with solid corners, also illustrated in figs. 1 and 2, only became practicable in consequence of the great improvements which had been made in the quality of steel plates; the credit of its invention formed the subject of litigation, which, however, was not carried to an issue. The abolition of corner Joints, which up to .1888 had been.made~ by dovetailing and by the use of angle irons, had been previously attempted by welding, but the process was abandoned as commercially impracticable.

Fig. 3.

In the early days of the safe industry in America the conditions as far as protection from fire was concerned were entirely different from those obtaining in Great Britain. The timber construction employed in American buildings rendered fires much more fierce, but at the same time of very short duration, not more than an hour or two, To meet this condition of affairs thick, sides of non-conducting materials were more efficacious than the, chambers of steam-generating, materials employed in British construction, but the gradual abandonment of timber and the increasing size of buildings have called for changes in the methods of fire-proofing.

The American “burglar proof” safe, (figs 4) seems to have developed from the fire-proof (fig, 5) Simply by the addition of extra thicknesses of metal, usually alternately hard and soft, without any serious increase of structural strength; this construction, known as the “laminated” or “built up,” offers little resistance to burglars, as the various layers can be separated from one another by the use either of explosives, especially nitroglycerin, or of wedges. In 1890 a commission was appointed by the U.S.A. government to report upon the strong-rooms or vaults of the treasury at Washington; and their report[1] was presented in September 1893. This commission) based their conclusions on experiments conducted in their presence, as well as on well-authenticated experiments performed by safe-makers on their own and other makers? productions, and they found

|

|

| Fig. 4.—American Burglar-proof Construction. | Fig. 5.—American Fire-proof Safe. |

that, with the single exception of the Corliss safe, all the safes which came under their notice—and these comprised all the best-known American makes—could be opened by burglars by

- ↑ Report of Special Commission of Experis as to Means of improving Vault facilities of the Treasury Department (Washington, 1894).