before the 19th century, that is to say, industries carried on with

capital and machinery in large factories. Industry of this character

was first established in Poland in 1820, and it has grown there

rapidly, though never so rapidly as during the last few years of the

19th century. The principal centre is Lodz in the government of

Piotrkow, the staple industry being cottons. A good many factories

have sprung up also in Warsaw and at Sosnowice and Bendzin in

the extreme S.W. corner of Poland. Besides cottons the products

include woollens and cloth, silks, chemicals, machinery, ironware,

beer and flour. At Lodz alone the workmen, in great part Germans

and Jews, number between 50,000 and 60,000, and the total output

of the factories is estimated at £9,000,000 to £10,500,000 annually.

Similar industries, carried on by similar methods, exist at St Petersburg,

Riga, Narva and Odessa. In S. Russia, more particularly at

Ekaterinoslav, a very vigorous metallurgical industry has grown up

since 1860 in conjunction with the iron and coal mining.

The peculiar feature of Russian industry is the development out of the domestic petty handicrafts of central Russia of a semi-factory on a large scale. Owing to the forced abstention from agricultural labour in the winter months the peasants of central Russia, more especially those of the governments of Moscow, Vladimir, Yaroslavl, Kostroma, Tver, Smolensk and Ryazañ have for centuries carried on a variety of domestic handicrafts during the period of compulsory leisure. The usual practice was for the whole of the people in one village to devote themselves to one special occupation. Thus, while one village would produce nothing but felt shoes, another would carve sacred images (ikons), and a third spin flax only, a fourth make wooden spoons, a fifth nails, a sixth iron chains, and so on. In the same way certain governments become famous for certain commodities, as Moscow for osier baskets, flower baskets, wicker furniture and lace; Kostroma for lace, wooden utensils, toys, wooden spoons, cups and bowls, bast sacks and mats, bast boots and garden products; Yaroslavl for furniture, brass samovars, saucepans, spurs, rings, &c.; Vladimir for furniture, osier baskets and flower-stands and sickles; Nizhniy-Novgorod for bast mats and sacks, knives, forks and scissors; Tver for lace, nails, sieves, anchors, fish-hooks, locks, coarse clay pottery, saddlery and harness, boots and shoes, and so on. Out of these have grown large factories, employing as many as 10,000 to 12,000 men each; but when harvest comes round, these men leave the factories and repair to their fields, and meantime the factories stand still for two or three months. Nor do the people work on the holidays of the church, the number of days they lose in this way amounting to nearly one-third of the whole year. Hence, although wages are painfully low, the cost of production to the manufacturer is relatively high; and it is still further increased by the cost of the raw materials, by the heavy rates of transport owing to the distance from the sea, by the dearness of capital and by the scarcity of fuel. As a consequence this central Russian industry, even when supported by very high protective duties, is only able to produce for the home market and the markets of the adjacent territories in Asia which are under Russian political control. Here again cotton is the principal product; and the remarkable growth of the industry is illustrated by the fact that, whereas in 1843 there were only 350,000 spindles at work, fifty years later there were 4,332,000 so employed, and in 1900, 6,554,600. The number of looms increased from 87,190 in 1890 to 154,600 in 1900. Next after cottons come woollens, silk, cloth, chemicals, machinery, paper, furniture, hats, cement, leather, glass and china and other products. From the governments of Vyatka and Vladimir large numbers of bricklayers, carpenters and other handicraftsmen migrate temporarily to the S. governments every year, and similarly plasterers and painters from the government of Moscow.

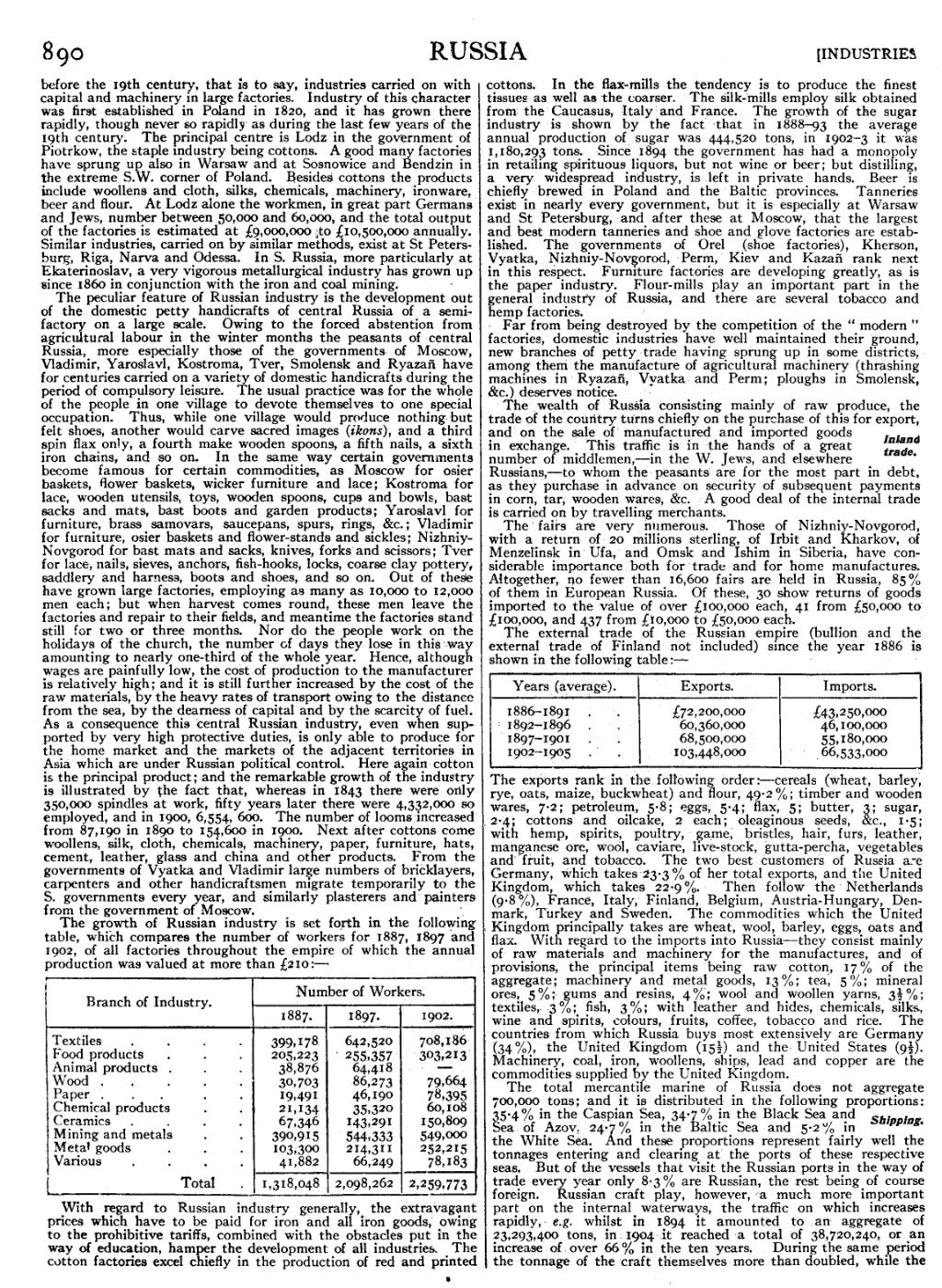

The growth of Russian industry is set forth in the following table, which compares the number of workers for 1887, 1897 and 1902, of all factories throughout the empire of which the annual production was valued at more than £210:—

| Branch of Industry. | Number of Workers. | ||

| 1887. | 1897. | 1902. | |

| Textiles | 399,178 | 642,520 | 708,186 |

| Food products | 205,223 | 255,357 | 303,213 |

| Animal products | 38,876 | 64,418 | — |

| Wood | 30,703 | 86,273 | 79,664 |

| Paper | 19,491 | 46,190 | 78,395 |

| Chemical products | 21,134 | 35,320 | 60,108 |

| Ceramics | 67,346 | 143,291 | 150,809 |

| Mining and metals | 390,915 | 544,333 | 549,000 |

| Metal goods | 103,300 | 214,311 | 252,215 |

| Various | 41,882 | 66,249 | 78,183 |

| Total | 1,318,048 | 2,098,262 | 2,259,773 |

With regard to Russian industry generally, the extravagant prices which have to be paid for iron and all iron goods, owing to the prohibitive tariffs, combined with the obstacles put in the way of education, hamper the development of all industries. The cotton factories excel chiefly in the production of red and printed cottons. In the flax-mills the tendency is to produce the finest tissues as well as the coarser. The silk-mills employ silk obtained from the Caucasus, Italy and France. The growth of the sugar industry is shown by the fact that in 1888-93 the average annual production of sugar was 444,520 tons, in 1902-3 it was 1,180,293 tons. Since 1894 the government has had a monopoly in retailing spirituous liquors, but not wine or beer; but distilling, a very widespread industry, is left in private hands. Beer is chiefly brewed in Poland and the Baltic provinces. Tanneries exist in nearly every government, but it is especially at Warsaw and St Petersburg, and after these at Moscow, that the largest and best modern tanneries and shoe and glove factories are established. The governments of Orel (shoe factories), Kherson, Vyatka, Nizhniy-Novgorod, Perm, Kiev and Kazañ rank next in this respect. Furniture factories are developing greatly, as is the paper industry. Flour-mills play an important part in the general industry of Russia, and there are several tobacco and hemp factories.

Far from being destroyed by the competition of the “modern” factories, domestic industries have well maintained their ground, new branches of petty trade having sprung up in some districts, among them the manufacture of agricultural machinery (thrashing machines in Ryazañ, Vyatka and Perm; ploughs in Smolensk, &c.) deserves notice.

The wealth of Russia consisting mainly of raw produce, the trade of the country turns chiefly on the purchase of this for export, Inland trade. and on the sale of manufactured and imported goods in exchange. This traffic is in the hands of a great trade number of middlemen,—in the W. Jews, and elsewhere Russians,—to whom the peasants are for the most part in debt, as they purchase in advance on security of subsequent payments in corn, tar, wooden wares, &c. A good deal of the internal trade is carried on by travelling merchants.

The fairs are very numerous. Those of Nizhniy-Novgorod, with a return of 20 millions sterling, of Irbit and Kharkov, of Menzelinsk in Ufa, and Omsk and Ishim in Siberia, have considerable importance both for trade and for home manufactures. Altogether, no fewer than 16,600 fairs are held in Russia, 85% of them in European Russia. Of these, 30 show returns of goods imported to the value of over £100,000 each, 41 from £50,000 to £100,000, and 437 from £10,000 to £50,000 each.

The external trade of the Russian empire (bullion and the external trade of Finland not included) since the year 1886 is shown in the following table:—

| Years (average). | Exports. | Imports. |

| 1886-1891 | £72,200,000 | £43,250,000 |

| 1892-1896 | 60,360,000 | 46,100,000 |

| 1897-1901 | 68,500,000 | 55,180,000 |

| 1902-1905 | 103,448,000 | 66,533,000 |

The exports rank in the following order:—cereals (wheat, barley, rye, oats, maize, buckwheat) and flour, 49.2%; timber and wooden wares, 7.2; petroleum, 5.8; eggs, 5.4; flax, 5; butter, 3; sugar, 2.4; cottons and oilcake, 2 each; oleaginous seeds, &c., 1.5; with hemp, spirits, poultry, game, bristles, hair, furs, leather, manganese ore, wool, caviare, live-stock, gutta-percha, vegetables and fruit, and tobacco. The two best customers of Russia are Germany, which takes 23.3% of her total exports, and the United Kingdom, which takes 22.9%. Then follow the Netherlands (9.8%), France, Italy, Finland, Belgium, Austria-Hungary, Denmark, Turkey and Sweden. The commodities which the United Kingdom principally takes are wheat, wool, barley, eggs, oats and flax. With regard to the imports into Russia they consist mainly of raw materials and machinery for the manufactures, and of provisions, the principal items being raw cotton, 17% of the aggregate; machinery and metal goods, 13%; tea, 5%; mineral ores, 5%; gums and resins, 4%; wool and woollen yarns, 3½%; textiles, 3%; fish, 3%; with leather and hides, chemicals, silks, wine and spirits, colours, fruits, coffee, tobacco and rice. The countries from which Russia buys most extensively are Germany (34%), the United Kingdom (15½) and the United States (9½). Machinery, coal, iron, woollens, ships, lead and copper are the commodities supplied by the United Kingdom.

The total mercantile marine of Russia does not aggregate 700,000 tons; and it is distributed in the following proportions: Shipping. 35.4% in the Caspian Sea, 34.7% in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov, 24.7% in the Baltic Sea and 5.2% in the White Sea. And these proportions represent fairly well the tonnages entering and clearing at the ports of these respective seas. But of the vessels that visit the Russian ports in the way of trade every year only 8.3% are Russian, the rest being of course foreign. Russian craft play, however, a much more important part on the internal waterways, the traffic on which increases rapidly, e.g. whilst in 1894 it amounted to an aggregate of 23,293,400 tons, in 1904 it reached a total of 38,720,240, or an increase of over 66% in the ten years. During the same period the tonnage of the craft themselves more than doubled, while the