distinguished by the compressed, rudder-shaped tail. They are unable to move on land, feed on fishes, are viviparous and poisonous.

The majority of snakes are active during the day, their energy increasing with the increasing temperature; whilst some delight in the moist sweltering heat of dense tropical vegetation, others expose themselves to the fiercest rays of the midday sun. Not a few, however, lead a nocturnal life, and many of them have, accordingly, their pupil contracted into a vertical or more rarely a horizontal slit. Those which inhabit temperate latitudes hibernate. Snakes are the most stationary of all vertebrates; as long as a locality affords them food and shelter they have no inducement to change it. Their dispersal, therefore, must have been extremely slow and gradual. Although able to move

Fig. 1.—Diagram of Natural Locomotion of a Snake.

with rapidity, they do not keep in motion for any length of time. Their organs of locomotion are the ribs, the number of which is very great, nearly corresponding to that of the vertebrae of the trunk. They can adapt their motions to every variation of the ground over which they move, yet all varieties of snake locomotion are founded on the following simple process. When a part of the body has found some projection of the ground which affords it a point of support, the ribs are drawn more closely together, on alternate sides, thereby producing alternate bends of the body. The hinder portion of the body being drawn after, some part of it (c) finds another support on the rough ground or a projection; and, the anterior bends being stretched in a straight line, the front part of the body is propelled (from a to d) in consequence. During this peculiar locomotion the numerous broad shields of the belly are of great advantage, as by means of their free edges the snake is enabled to catch and use as points of support the slightest projections of the ground. A pair of ribs corresponds to each of these ventral shields. Snakes are not able to move over a perfectly smooth surface. The conventional representation of the progress of a snake, in which its undulating body is figured as resting by a series of lower bends on the ground whilst the alternate bends are

Fig. 2.—Diagram of Conventional Idea of a Snake's Locomotion.

raised above it, is an impossible attitude, nor do snakes ever climb trees in spiral fashion, the classical artistic mode of representation. Also the notion that snakes when attacking are able to jump off the ground is quite erroneous; when they strike an object, they dart the fore part of their body, which was retracted in several bends, forwards in a straight line. And sometimes very active snakes, like the cobra, advance simultaneously with the remainder of the body, which, however, glides in the ordinary fashion over the ground; but no snake is able to impart such an impetus to the whole of its body as to lose its contact with the ground. Some snakes can raise the anterior part of their body and even move in this attitude, but it is only about the anterior fourth or third of the total length which can be thus erected.

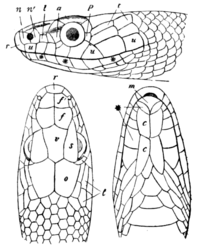

With very few exceptions, the integuments form imbricate scale-like folds arranged with the greatest regularity; they are small and pluriserial on the upper parts of the body and tail, large and uniserial on the abdomen, and generally biserial on the lower side of the tail. The folds can be stretched out, so that the skin is capable of a great degree of distension. The scales are sometimes rounded behind, but generally rhombic in shape and more or less elongate; they may be quite smooth or provided with a longitudinal ridge or heel in the middle line. The integuments of the head are divided into non-imbricate shields or plates, symmetrically arranged, but not corresponding in size or shape with the underlying cranial bones or having any relation to them. The form and number of the scales and scutes, and the shape and arrangement of the head-shields, are of great value in distinguishing the genera and species, and it will therefore be useful to explain in the accompanying woodcut (fig. 3) the terms by which these parts are designated. The skin does not form eyelids; but the epidermis passes over the eye, forming a transparent disk, concave like the glass of a watch, behind which the eye moves. It is the first part which is cast off when the snake sheds its skin; this is done several times in the year, and the epidermis comes off in a single piece, being, from the mouth towards the tail, turned inside out during the process.

The tongue in snakes is narrow, almost worm-like, generally of a black colour and forked, that is, it terminates in front in two extremely fine filaments. It is often exserted with a rapid motion, sometimes with the object of feeling some object, sometimes under the influence of anger or fear.

Dentition.

Snakes possess teeth in the maxillaries, mandibles, palatine and pterygoid bones, sometimes also in the intermaxillary; they may be absent in one or the other of the bones mentioned. In the innocuous snakes the teeth are simple and uniform in structure, thin, sharp like needles, and bent backwards; their function consists merely in seizing and holding the prey. In some all the teeth are nearly of the same size; others possess in front of the jaws (Lycodonts) or behind in the maxillaries (Diacrasterians) a tooth more or less conspicuously larger than the rest; whilst others again are distinguished by this larger posterior tooth being grooved along its outer face. The snakes with this grooved kind of tooth have been named Opisthoglyphi, and also Suspecti, because their saliva is more or less poisonous. In the true poisonous snakes the maxillary dentition has undergone a special modification. The so-called colubrine venomous snakes, which retain in a great measure an external resemblance to the innocuous snakes, have the maxillary bone not at all, or but little, shortened, armed in front with a fixed, erect fang, which is provided with a deep groove or canal for the conveyance of the poison, the fluid being secreted by a special poison-gland. One or more small ordinary teeth may be placed at some distance behind this poison-fang. In the other venomous snakes (viperines and crotalines) the maxillary bone is very short, and is armed with a single very long curved fang with a canal and aperture at each end. Although firmly anchylosed to the bone, the tooth, which when at rest is laid backwards, is erectile,—the

Fig. 3.—Head-shields of a Snake (Ptyas korros).

r, Rostral.

f, Posterior frontal.

f′, Anterior frontal.

v, Vertical.

s, Supraciliary or supraocular.

o, Occipital.

n, n′, Nasals.

l, Loreal.

a, Anterior ocular or orbital, or prae-orbital or anteocular.

p, Postoculars.

u, u, Upper labials.

t, t, Temporals.

m, Mental.

*, *, Lower labials.

c, c, Chin-shields.

bone itself being mobile and rotated round its transverse axis. One or more reserve teeth, in various stages of development, lie between the folds of the gum and are ready to take the place of the one in function whenever it is lost by accident, or shed.

The poison is secreted in modified upper labial glands, or in a pair of large glands which are the homologues of the parotid salivary glands of other animals. For a detailed account see West, J. Linn. Soc. xxv. (1895), p. 419; xxvi. (1898), p. 517; and xxviii. (1900). A duct leads to the furrow or canal of the tooth. The Elapinae have comparatively short fangs, while those of the vipers, especially the crotaline snakes, are much longer, sometimes nearly an inch in length. The Viperidae alone have "erectile" fangs. The mechanism is explained by the diagrams (fig. 4). The poison-bag lies on the side of the head between the eye and the mandibular joint and is held in position by strong ligaments which are attached to this joint and to the maxilla so that the act of opening the jaws and concomitant erection of the fangs automatically squeezes the poison out of the glands.

Snakes are carnivorous, and as a rule take living prey only; a few feed habitually or occasionally on eggs. Many swallow