Values of the entropy of water and steam are given in the table.

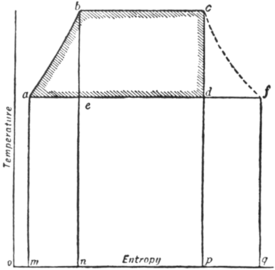

The entropy-temperature diagram for a Rankine cycle is illustrated

in fig. 11, where 𝑎𝑏, a

logarithmic curve, represents

the process of heating

the feed-water, and

𝑏𝑐 the passage from the

state of water into that

of steam. The diagram

is drawn to scale for a

case in which steam is

formed at a pressure of

180 ℔ per sq. in., and

condensed at a pressure

of 1 ℔ per sq. in. After

the formation of the

steam, the next step in

the ideal process is

adiabatic expansion from

the higher to the lower

limit of temperature,

which is represented by

the vertical straight line

𝑐𝑑, an adiabatic process

being also isentropic. Finally, the cycle is completed by 𝑑𝑎, which represents

the condensation of the steam after its temperature has been

reduced by adiabatic expansion to the lower limit of temperature.

The area 𝑎𝑏𝑐𝑑 represents the work done, and its value per ℔ of

steam is identical with W as reckoned above. The area 𝑚𝑎𝑏𝑐𝑝 is

the whole heat taken in, and the area 𝑚𝑎𝑑𝑝 is the heat rejected.

Let a curve 𝑐𝑓 be drawn to show the values of the entropy of steam for various temperatures of saturation: then if 𝑎𝑑 be produced to meet the curve in 𝑓, the ratio 𝑓𝑑/𝑓𝑎 represents the fraction of the steam which was condensed during adiabatic expansion. For the point 𝑓 represents the state of 1 ℔ of saturated steam, and in the condensation of 1 ℔ of saturated steam the heat given out would be the area under 𝑓𝑎, whereas the heat actually given out in the condensation from 𝑑 was the area under 𝑑𝑎. Thus the state at 𝑑 is that of a wet mixture in which 𝑑𝑎/𝑓𝑎 represents the fraction present as steam, and 𝑓𝑑/𝑓𝑎 the fraction present as water. It obviously follows that by drawing horizontal lines at intermediate temperatures the development of wetness in the expanding steam can be readily traced. Again, if the steam is not dry when expansion begins, its state may be represented by making the expansion line begin at a point in the line 𝑏𝑐, such that the segments into which the line is divided are proportional to the constituents of the wet mixture. In this way the ideal process may be exhibited for steam with any assumed degree of initial wetness. Further, the entropy-temperature diagram admits of ready application to the case of incomplete expansion. Suppose, for example, that after adiabatic expansion from 𝑐 to 𝑐′ (fig. 12) the steam is directly cooled to the lower-limit temperature by the application of cooling water instead of by continued expansion. This process is represented by the line 𝑐′𝑒𝑑, which is a curve of constant volume. Its form is determined by the consideration that at any point 𝑒 the proportion of steam still uncondensed, or 𝑙𝑒/𝑙𝑘, is such that the mixture fills the same volume as was filled at 𝑐′.

43. Entropy-Temperature Diagrams extended to the Case of Superheated Steam.—In

the diagrams which have been sketched, it has

been assumed that the

steam is supplied to the

engine in a saturated state.

To extend the same treatment

to the case of superheated

steam, we have to

take account of the supplementary

supply of heat

which the steam receives

after the point 𝑐 is reached,

and before expansion begins.

When superheating

is resorted to, as is now

often the case in practice,

the superheat is given at

constant pressure. If κ

represent as before the

mean specific heat of steam

at constant pressure, the

addition of entropy during

the process of superheating from τ1 to τ′ is κ(τ′ − τ1). The value of

κ may be treated as approximately constant, and the addition to

the entropy may then be written as κ(log τ − log τ1). This gives a

line such as 𝑐𝑟 on the entropy diagram (fig. 13), and increases

the value of W by the amount

which is represented on the diagram by the area 𝑑𝑐𝑟𝑠. During adiabatic expansion from 𝑟 the steam remains superheated until it reaches the state 𝑡, when it is just saturated, and further expansion results in the condition of wetness indicated by 𝑠. The extra work 𝑑𝑐𝑟𝑠 is done at the expense of the extra supply of heat 𝑝𝑐𝑟𝑢, and an inspection of the diagram suffices to show that the efficiency of the ideal cycle is only very slightly increased by even a large amount of superheating. In practice, however, superheating does much to promote efficiency, because it materially reduces the amount by which the actual performance of an engine falls short of the ideal performance by keeping the steam comparatively dry in its passage through the engine, and thereby reducing exchanges ot heat between the steam and the metal.

44. Entropy of Wet Steam.—The entropy of wet steam is readily calculated by considering that the change of entropy in the conversion from water to steam will be 𝑞L/τ if the steam is wet, 𝑞 being the dryness Accordingly the entropy of wet steam at any temperature τ is σ(logετ − logετ0)+𝑞L/τ. Further, since σ for water is practically equal to unity this expression may be written

φ=logετ − logετ0+𝑞L/τ.

We may apply this expression to trace the development of wetness in steam when it expands adiabatically. In adiabatic expansion φ=constant. Using the suffix 1 to distinguish the initial state, we therefore have at any stage in the expansion

logετ − logετ0=logετ1 − logετ0 +𝑞1L1/τ1,

from which the dryness at that stage is found, namely,

𝑞=τL(𝑞1L1τ1 + logετ1τ1).

The expression is not applicable to steam which is initially superheated. In either case the graphic method of tracing the change of condition during adiabatic expansion is available.

45. Actual Performance.—Trials of engines using saturated steam

show that in the most favourable cases from 60 to 65% of the ideally

possible amount of work is realized as “indicated” work One

of the causes of loss is that the expansion is incomplete. In practice

the steam is allowed to escape to the condenser, while its pressure

is still considerably higher than the pressure at which condensation

is to take place. When the pressure of steam in the cylinder has

been so far reduced by expansion that it can only overcome the

friction of the piston, there is no advantage in going on further;

the indicated work due to any additional expansion would add

nothing to the output of the engine, when allowance is made for

the work spent on friction within the mechanism itself. Considerations

of bulk often lead to an even earlier release of the expanding

steam; and another consideration which points the same way is that

when expansion is carried very far, the losses due to exchange of

heat between the cylinder and the steam, referred to below, tend

to increase. Again, since experience shows that the most efficient

engines are those in which the process of expansion is divided into

two, three or more stages by the use of compounded cylinders,

a certain amount of loss is to be ascribed to the drops in pressure

which are liable to occur through unresisted expansion in the transfer

of steam from one vessel to another. But the chief cause of loss

is to be found in the exchanges of heat which take place between

the steam and the metal. In each cylinder there is a process of

alternate condensation and re-evaporation—condensation during

the period of admission, when the steam finds itself brought into

contact with metal which has been chilled by evaporation during

the preceding exhaust stroke, and then evaporation, when the

pressure has fallen sufficiently, during the later stage of expansion,

as well as during exhaust. The consequence is that the steam

though supplied in a dry

Fig. 14

state, may contain some 20

or 30% of moisture when

admission to the cylinder is

complete, and the entropy

diagram for the real process

of expansion takes a form

such as is indicated by the

line 𝑐′𝑐″ in fig. 14. The heat

supplied is still measured by

the area under 𝑎𝑏𝑐. The

condensation from 𝑐 to 𝑐′ occurs by contact with the walls of the

cylinder; and though part of the heat thus abstracted is restored

before release occurs at 𝑐″ , the general result is to make a large

reduction in the area of the diagram.

46. Exchanges of Heat between the Steam and the Metal.—The exchanges of heat between steam and metal in the engine cylinder have been made the subject of an elaborate experimental examination