isthmus to be surveyed as a preliminary to the digging of a canal across it, and the engineer he employed, J. M. Lepère, came to the conclusion that there was a difference in level of 29 ft. between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. This view was combated at the time by Laplace and Fourier on general grounds, and was finally disproved in 1846–1847 as the result of surveys made at the instance of the Société d’Ếtudes pour le Canal de Suez. This society was organized in 1846 by Prosper Enfantin, the Saint Simonist, who thirteen years before had visited Egypt in connexion with a scheme for making a canal across the isthmus of Suez, which, like the canal across the isthmus of Panama, was part of the Saint Simonist programme for the regeneration of the world. The expert commission appointed by this society reported by a majority in favour of Paulin Talabot’s plan, according to which the canal would have run from Suez to Alexandria by way of Cairo.

| |

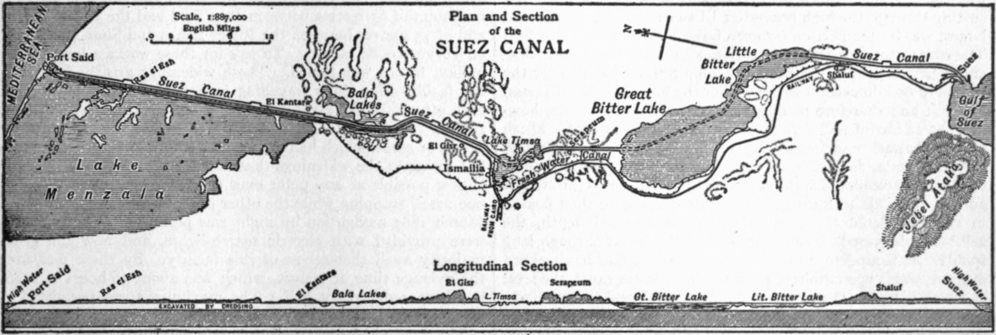

| (Topography only from L’Isthme et le Canal de Suez, by G. Charles-Roux, by permission of Messrs Hachette & Co.) | Emery Walker sc. |

For some years after this report no progress was made; indeed, the society was in a state of suspended animation when in 1854 Ferdinand de Lesseps came to the front as the chief exponent of the idea. He had been associated with the Saint Simonists and for many years had been keenly interested in the question. His opportunity came in 1854 when, on the death of Abbas Pasha, his friend Said Pasha became viceroy of Egypt. From Said on the 30th of November 1854 he obtained a concession authorizing him to constitute the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez, which should construct a ship canal through the isthmus, and soon afterwards in concert with two French engineers, Linant Bey and Mougel Bey, he decided that the canal should run in a direct line from Suez to the Gulf of Pelusium, passing through the depressions that are now Lake Timsa and the Bitter Lakes, and skirting the eastern edge of Lake Menzala. In the following year an international commission appointed by the viceroy approved this plan with slight modifications, the chief being that the channel was taken through Lake Menzala instead of along its edge, and the northern termination of the canal moved some 1712 m. westward where deep water was found closer to the shore. This plan, according to which there were to be no locks, was the one ultimately carried out, and it was embodied in a second and amplified concession, dated the 5th of January 1856, which laid on the company the obligation of constructing, in addition to the maritime canal, a fresh-water canal from the Nile near Cairo to Lake Tirnsa, with branches running parallel to the maritime canal, one to Suez and the other to Pelusium. The concession was to last for 99 years from the date of the opening of the canal between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean, after which, in default of other arrangements, the canal passes into the hands of the Egyptian government. The confirmation of the sultan of Turkey being required, de Lesseps went to Constantinople to secure it, but found himself baffled by British diplomacy; and later in London he was informed by Lord Palmerston that in the opinion of the British government the canal was a physical impossibility, that if it were made it would injure British maritime supremacy, and that the proposal was merely a device for French interference in the East.

Although the sultan’s confirmation of the concession was not actually granted till 1866, de Lesseps in 1858 opened the subscription lists for his company, the capital of which was 200 million francs in 400,000 shares of 500 francs each. In less than a month 314,494 shares were applied for; of these over 200,000 were subscribed in France and over 96,000 were taken by the Ottoman Empire. From other countries the subscriptions were trifling, and England, Austria and Russia, as well as the United States of America, held entirely aloof. The residue of 85,506 shares[1] was taken over by the viceroy. On the 25th of April 1859 the work of construction was formally begun, the first spadeful of sand being turned near the site of Port Said, but progress was not very rapid. By the beginning of 1862 the freshwater canal had reached Lake Timsa, and towards the end of the same year a narrow channel had been formed between that lake and the Mediterranean. In 1863 the fresh-water canal was continued to Suez.

So far the work had been performed by native labour; the concession of 1856 contained a provision that at least four-fifths of the labourers should be Egyptians, and later in the same year Said Pasha undertook to supply labourers as required by the engineers of the canal company, which was to house and feed them and pay them at stipulated rates. Although the wages and the terms of service were better than the men obtained normally, this system of forced labour was strongly disapproved of in England, and the khedive Ismail who succeeded Said on the latter’s death in 1863 also considered it as being contrary to the interests of his country. Hence in July the Egyptian foreign minister, Nubar Pasha, was sent to Constantinople with the proposal that the number of labourers furnished to the company should be reduced, and that it should be made to hand back to the Egyptian government the lands that had been granted it by Said in 1856. These propositions were approved by the sultan, and the company was informed that if they were not accepted the works would be stopped by force. Naturally the company objected, and in the end the various matters in dispute were referred to the arbitration of the emperor Napoleon III. By his award, made in July 1864, the company was allowed 38 million francs as an indemnity for the abolition of the corvée, 16 million francs in respect of its retro cessions of that portion off the freshwater canal that lay between Wadi, Lake Timsa and Suez (the remainder had already been handed back by agreement), and 30 million francs in respect of the lands which had been granted it by Said. The company was allowed to retain a certain amount of land along the canals, which was necessary for purposes of construction, erection of workshops, &c., and it was put under the obligation of finishing the fresh-water canal between Wadi and

- ↑ These formed part of the 176,602 shares which were bought for the sum of £3,975,582 from the khedive by England in 1875 at the instance of Lord Beaconsfield (q.v.).