giving a theoretical fundamental tone and its upper partials a semitone lower than the last, and corresponding to the seven shifts on the violin and to the seven positions on valve instruments. These seven positions are found by drawing out the slide a little more for each one, the first position being that in which the slide remains closed. The performer on the trombone is just as dependent on an accurate ear for finding the correct positions as a violinist.

The table of harmonics for the seven positions of the tenor trombone in B♭ is appended; they furnish a complete chromatic compass of two octaves and a sixth.

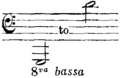

| Position I. (with closed slide). |

|

| II. |  |

| III. |  |

| IV. | |

| V. |  |

| VI. |  |

| VII. |

These notes represent all the notes in practical use, although it is possible to produce certain of the higher harmonics. The instrument being non-transposing, the notation represents the real sounds.

The four chief trombones used in the orchestra are the following: —

| The Alto in E flat or F. |  |

| The Tenor-Bass in B flat. |  |

| The Bass in F or G (with double slide in E flat). |

|

| The Contra-Bass in B flat. An octave below the Tenor-Bass. |

|

The compass given above is extreme and includes the notes obtained by means of the slide; the notes in brackets are very difficult; the fundamental notes, even when they can be played, are not of much practical use. The contra-bass trombone, although not much in request in the concert hall, is required for the Nibelungen Ring, in which Wagner has scored effectively for it.

The quality of tone varies greatly in the different instruments and registers. The alto trombone has neither power nor richness of tone, but sounds hard and has a timbre between that of a trumpet and a French horn. The tenor and bass have a full rich quality suitable for heroic, majestic music, but the tone depends greatly on the performer's method of playing; the modern tendency to produce a harsh, noisy blare is greatly to be deplored.

Besides the slide trombone, which is most largely used, there are the valve trombones, and the double-slide trombones. The former are made in the same keys as the instruments given above and are constructed in the same manner, except that the slide is replaced by three pistons, which enable the performer to obtain a greater technical execution; as the tone suffers thereby and loses its characteristic timbre, the instruments have never become popular in England.

The double-slide trombone (fig. 2) — patented by Messrs Rudall Carte & Co. but said to have been originally invented by Halary in 1830 — is made in B♭, G bass and E♭ contrabass. In these instruments each of the branches of the slide is made half the usual length. There are four branches instead of two and the two pairs lie one over the other, each pair being connected at the bottom by a semicircular tube and the second pair similarly at the top as well. The usual bar or stay suffices for drawing out both pairs of slides simultaneously, but as the lengthening of the air column is now doubled in proportion to the shift of the slide, the extension of arm for the lower positions is lessened by half, which increases the facility of execution but calls for greater nicety in the adjustment of the slide, more especially in the higher positions.

The history of the evolution of the trombone from the buccina is given in the article on the Sackbut (q.v.), the name by which the earliest draw or slide trumpets were known in England. The Germans call the trombone Posaune, formerly buzaun, busine, pusin or pusun in the poems and romances of the 12th and 13th century, words all clearly derived from the Latin buccina. The modern designation “large trumpet” comes from the Italian, in which tromba means not only trumpet, but also pump and elephant's trunk. It is difficult to say where or at what epoch the instrument was invented. In a psalter (No. 20) of the 11th century, preserved at Boulogne, there is a drawing of an instrument which bears a great resemblance to a trombone deprived of its bell. Sebastian Virdung, Ottmar Luscinius, and Martin Agricola say little about the trombone, but they give illustrations of it under the name of busaun which show that early in the 16th century it was almost the same as that employed in our day. It would not be correct to assume from this that the trombone was not well known at that date in Germany, and for the following reasons. First, the art of trombone playing was in the 15th century in Germany mostly in the hands of the members of the town bands, whose duties included playing on the watch towers, in churches, at pageants, banquets and festivals, and they, being jealous of their privileges, kept the secrets of their art closely, so that writers, such as the above, although acquainted with the appearance, tone and action of the instrument would have but little opportunity of learning much about the method of producing the sound. Secondly, German and Dutch trombone players are known to have been in request during the 15th century at the courts of Italian princes.[1] Thirdly, Hans Neuschel of Nuremberg, the most celebrated performer and maker of his day, had already won a name at the end of the 15th century for the excellence of his “Posaunen,” and it is recorded that he made great improvements in the construction of the instrument in 1498,[2] a date which probably marks the transition from sackbut to trombone, by enlarging the bore and turning the bell-joint round at right angles to the slide. Finally in early German translations of Vegetius's De re militari (1470) the buccina is described (bk. III., 5) as the trumpet or posaun which is drawn in and out, showing that the instrument was not only well known, but that it had been identified as the descendant of the buccina.

By the 16th century the trombone had come into vogue in England, and from the name it bore at first, not sackbut, but shakbusshe, it