the American Civil War. A notable instance was the destruction

of the Confederate ironclad “Albemarle” at the end of October

1864. On this mission Lieut. Cushing took a steam launch

equipped with an outrigger torpedo up the Roanoke River, in

which lay the “Albemarle.” On arriving near the ship Cushing

found her surrounded by logs, but pushing his boat over them,

he immersed the spar and exploded his charge in contact with

the “Albemarle” under a heavy fire. Ship and launch sank

together, but the gallant officer jumped overboard, swam away

and escaped. Submerged boats were also used for similar

service, but usually went to the bottom with their crews.

During the war between France and China in 1884 the “Yang

Woo” was attacked and destroyed by an outrigger torpedo.

Locomotive Torpedoes.—Though the spar torpedo had scored some successes, it was mainly because the means of defence against it at that time were inefficient. The ship trusted solely to her heavy gun and rifle fire to repel the attack. The noise, smoke, and difficulty of hitting a small object at night with a piece that could probably be discharged but once before the boat arrived, while rifle bullets would not stop its advance, favoured the attack. When a number of small guns and electric lights were added to a ship’s equipment, success with an outrigger torpedo became nearly, if not entirely, impossible. Attention was then turned in the direction of giving motion to the torpedo and steering it to the required point by electric wires worked from the shore or from another vessel; or, dispensing with any such connection, of devising a torpedo which would travel under water in a given direction by means of self-contained motive power and machinery. Of the former type are the Lay, Sims-Edison and Brennan torpedoes. The first two-electrically steered by a wire which trails behind the torpedo—have insufficient speed to be of practical value, and are no longer used. The Brennan torpedo, carrying a charge of explosive, travels under water and is propelled by unwinding two drums or reels of fine steel wire within the torpedo. The rotation of these reels is communicated to the propellers, causing the torpedo to advance. The ends of the wires are connected to an engine on shore to give rapid unwinding and increased speed to the torpedo; It is steered by varying the speed of unwinding the two wires. This torpedo was adopted by the British war office for harbour defence and the protection of narrow channels.

Uncontrolled Torpedoes.—The objection of naval officers to have any form of torpedo connected by wire to their ship during an action, impeding her free movement, liable to get entangled in her propellers and perhaps exploding where not desired—disadvantages which led them to discard the Harvey towing torpedo many years ago—has hitherto prevented any navy from adopting a controlled torpedo for its sea-going fleet. The last quarter of the 19th century saw, however, great advances in the equipment of ships with locomotive torpedoes of the uncontrolled type. The Howell may be briefly described, as it has a special feature of some interest. Motive power is provided by causing a heavy steel fly-wheel inside the torpedo to revolve with great velocity. This is effected by a small special engine outside operating on the axle. When sufficiently spun up, the axle of the flywheel is connected with the propeller shafts and screws which drive the torpedo, so that on entering the water it is driven ahead and continues its course until the power stored up in the flywheel is exhausted. Now when a torpedo is discharged into the sea from a ship in motion, it has a tendency to deflect owing to the action of the passing water. The angle of reflexion will vary according to the speed of the ship, and is also affected by other causes, such as the position in the ship from which the torpedo is discharged, and its own angle with the line of keel. Hence arise inaccuracies of shooting; but these do not occur with this torpedo, for the motion of the flywheel, acting as a gyroscope—the principle of which applied to the Whitehead torpedo is described later-keeps this torpedo on a straight course. This advantage, combined with simplicity in construction, induced the American naval authorities at one time to contemplate equipping their fleet with this torpedo, for they had not, up to Within a few years ago, adopted any locomotive torpedo. A great improvement in the torpedo devised by Mr Whitehead led them, however, definitely to prefer the latter and to discontinue the further development of the Howell system.

The Whitehead torpedo is a steel fish-shaped body which travels under water at a high rate of speed, being propelled by two screws driven by compressed air. It carries a large charge of explosive which is ignited on the torpedo striking any hard substance, such as the hull of a ship. The body is divided into three parts. The foremost portion or head contains the explosive—usually wet gun-cotton—with dry primer and mechanical igniting arrangement; the centre portion is the air chamber or reservoir, while the remaining part or tail carries the engines, rudders, and propellers besides the apparatus for controlling depth and direction. This portion also gives buoyancy to the torpedo.

When the torpedo is projected from a ship or boat into the water a lever is thrown back, admitting air into the engines causing the propellers to revolve and drive the torpedo ahead. It is desirable that a certain depth under water should be maintained. An explosion on the surface would be deprived of the greater part of its effect, for most of the gas generated would escape into the air. Immersed, the water above confines the liberated gas and compels it to exert all its energy against the bottom of the ship. It is also necessary to correct the tendency to rise that is due to the torpedo getting lighter as the air is used up, for compressed air has an appreciable weight. This is effected by an ingenious apparatus long maintained secret. The general principle is to utilize the pressures due to different depths of water to actuate horizontal rudders, so that the torpedo is automatically directed upwards or downwards as its tendency is to sink or rise.

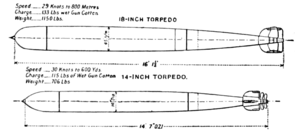

Fig. 1.—Diagrams of 14- and 18-in. Torpedoes.

The efficiency of such a torpedo compared with all previous types was clearly manifest when it was brought before the maritime states by the inventor, Whitehead, and it was almost universally adopted. The principal defect was want of speed—which at first did not exceed 10 knots an hour—but by the application of Brotherhood’s 3-cylinder engine the speed was increased to 18 knots—a great advance. From that time continuous improvements have resulted in speeds of 30 knots and upwards for a short range being obtained. For some years a torpedo 14 ft. long and 14 in. in diameter was considered large enough, though it had a very limited effective range. For a longer range a larger weapon must be employed capable of carrying a greater supply of air. To obtain this, torpedoes of 18 in. diameter, involving increased length and weight, have for some time been constructed, and have taken the place of the smaller torpedo in the equipment of warships. This advance in dimensions has not only given a faster and steadier torpedo, but enabled such a heavy charge of gun-cotton to be carried that its explosion against any portion of a ship would inevitably either sink or disable her. The dimensions, shape, &c., of the 14- and 18-in. torpedoes are shown in fig. 1. A limited range was still imposed by the uncertainty of its course under water. The speed of the ship from which it was discharged, the angle with her keel at which it entered the water, and the varying velocity of impulse, tended to error of flight, such error being magnified the farther the path of the torpedo was prolonged. Hence 800 yds. was formerly considered the limit of distance within which the torpedo should be discharged at sea against an object from a ship in motion.

In these circumstances, though improvements in the manufacture of steel and engines allowed of torpedoes of far longer range being