separating a possible effect produced in this way from the zodiacal light proper may seem to offer some difficulty. But the few observations made show that, after ordinary twilight has ended in the evening, the northern base of the zodiacal light extends more and more toward the north as the hours pass until, towards midnight, it merges into the light of the sky described by the two observers mentioned. Yet more conclusive are the observations of Maxwell Hall at Jamaica, who reached conclusions identical with those of Barnard and Newcomb, from observations of the base of the light at the close of twilight, which he estimated at 60° in the line through the sun.

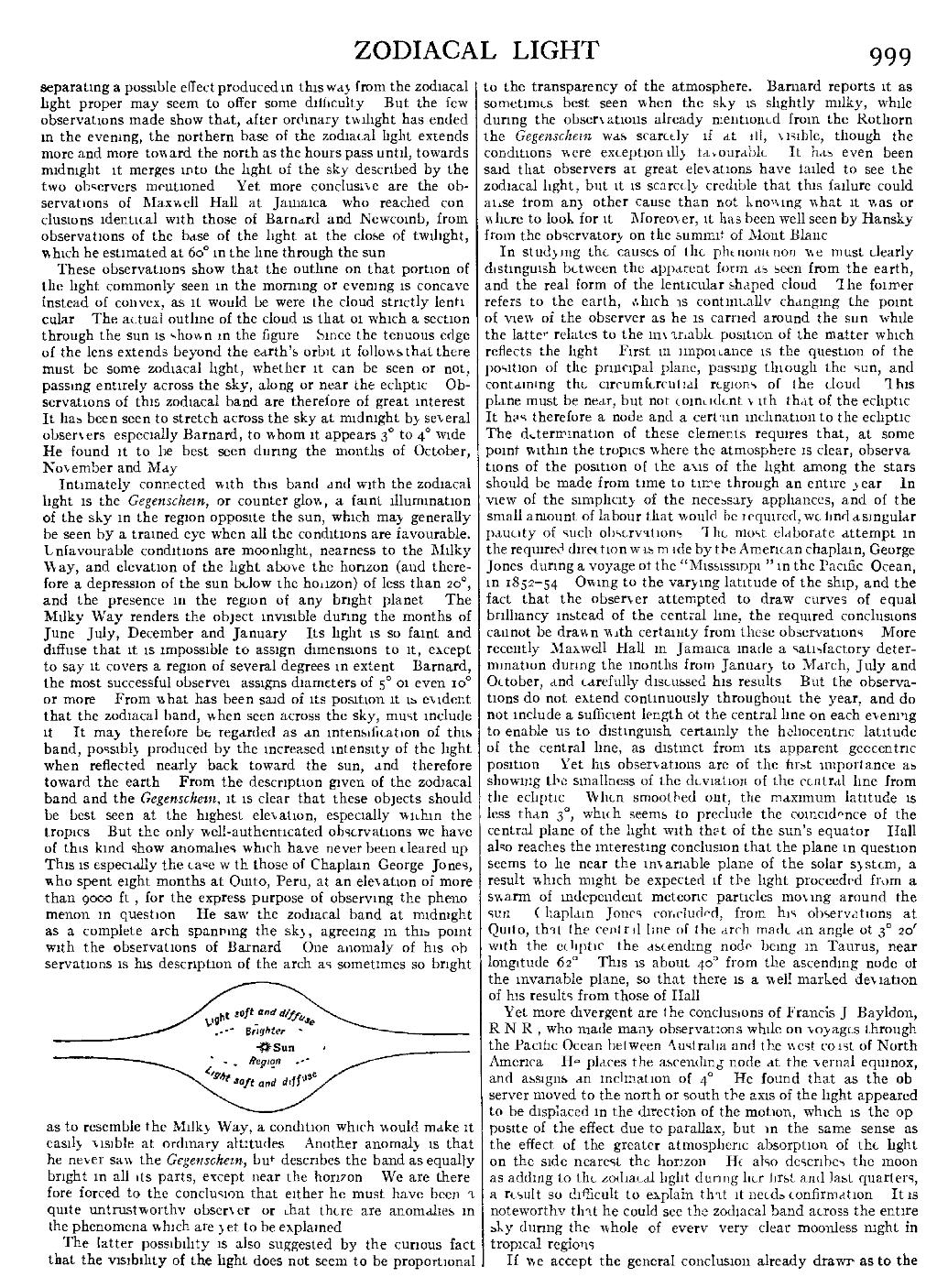

These observations show that the outline on that portion of the light commonly seen in the morning or evening is concave instead of convex, as it would be were the cloud strictly lenticular. The actual outline of the cloud is that of which a section through the sun is shown in the figure. Since the tenuous edge of the lens extends beyond the earth's orbit it follows that there must be some zodiacal light, whether it can be seen or not, passing entirely across the sky, along or near the ecliptic. Observations of this zodiacal band are therefore of great interest. It has been seen to stretch across the sky at midnight by several observers, especially Barnard, to whom it appears 3° to 4° wide. He found it to be best seen during the months of October, November and May.

Intimately connected with this band and with the zodiacal light is the Gegenschein, or counter-glow, a faint illumination of the sky in the region opposite the sun, which may generally be seen by a trained eye when all the conditions are favourable. Unfavourable conditions are moonlight, nearness to the Milky Way, and elevation of the light above the horizon (and therefore a depression of the sun below the horizon) of less than 20°, and the presence in the region of any bright planet. The Milky Way renders the object invisible during the months of June, July, December and January. Its light is so faint and diffuse that it is impossible to assign dimensions to it, except to say it covers a region of several degrees in extent. Barnard, the most successful observer, assigns diameters of 5° or even 10° or more. From what has been said of its position it is evident that the zodiacal band, when seen across the sky, must include it. It may therefore be regarded as an intensification of this band, possibly produced by the increased intensity of the light when reflected nearly back toward the sun, and therefore toward the earth. From the description given of the zodiacal band and the Gegenschein, it is clear that these objects should be best seen at the highest elevation, especially within the tropics. But the only well-authenticated observations we have of this kind show anomalies which have never been cleared up. This is especially the case with those of Chaplain George Jones, who spent eight months at Quito, Peru, at an elevation of more than 9000 ft., for the express purpose of observing the phenomenon in question. He saw the zodiacal band at midnight as a complete arch spanning the sky, agreeing in this point with the observations of Barnard. One anomaly of his observations is his description of the arch as sometimes so bright as to resemble the Milky Way, a condition which would make it easily visible at ordinary altitudes. Another anomaly is that he never saw the Gegenschein, but describes the band as equally bright in all its parts, except near the horizon. We are therefore forced to the conclusion that either he must have been a quite untrustworthy observer, or that there are anomalies in the phenomena which are yet to be explained.

The latter possibility is also suggested by the curious fact that the visibility of the light does not seem to be proportional to the transparency of the atmosphere. Barnard reports it as sometimes best seen when the sky is slightly milky, while during the observations already mentioned from the Rothorn the Gegenschein was scarcely, if at all, visible, though the conditions were exceptionally favourable. It has even been said that observers at great elevations have failed to see the zodiacal light; but it is scarcely credible that this failure could arise from any other cause than not knowing what it was or where to look for it. Moreover, it has been well seen by Hansky from the observatory on the summit of Mont Blanc.

In studying the causes of the phenomenon we must clearly distinguish between the apparent form as seen from the earth, and the real form of the lenticular-shaped cloud. The former refers to the earth, which is continually changing the point of view of the observer as he is carried around the sun, while the latter relates to the invariable position of the matter which reflects the light. First in importance is the question of the position of the principal plane, passing through the sun, and containing the circumferential regions of the cloud. This plane must be near, but not coincident with, that of the ecliptic. It has therefore a node and a certain inclination to the ecliptic. The determination of these elements requires that, at some point within the tropics where the atmosphere is clear, observations of the position of the axis of the light among the stars should be made from time to time through an entire year. In view of the simplicity of the necessary appliances, and of the small amount of labour that would be required, we find a singular paucity of such observations. The most elaborate attempt in the required direction was made by the American chaplain, George Jones, during a voyage of the “Mississippi” in the Pacific Ocean, in 1852-54. Owing to the varying latitude of the ship, and the fact that the observer attempted to draw curves of equal brilliancy instead of the central line, the required conclusions cannot be drawn with certainty from these observations. More recently Maxwell Hall in Jamaica made a satisfactory determination during the months from January to March, July and October, and carefully discussed his results. But the observations do not extend continuously throughout the year, and do not include a sufficient length of the central line on each evening to enable us to distinguish certainly the heliocentric latitude of the central line, as distinct from its apparent geocentric position. Yet his observations are of the first importance as showing the smallness of the deviation of the central line from the ecliptic. When smoothed out, the maximum latitude is less than 3°, which seems to preclude the coincidence of the central plane of the light with that of the sun's equator. Hall also reaches the interesting conclusion that the plane in question seems to lie near the invariable plane of the solar system, a result which might be expected if the light proceeded from a swarm of independent meteoric particles moving around the sun. Chaplain Jones concluded, from his observations at Quito, that the central line of the arch made an angle of 3° 20′ with the ecliptic, the ascending node being in Taurus, near longitude 62°. This is about 40° from the ascending node of the invariable plane, so that there is a well-marked deviation of his results from those of Hall.

Yet more divergent are the conclusions of Francis J. Bayldon, R.N.R., who made many observations while on voyages through the Pacific Ocean between Australia and the west coast of North America. He places the ascending node at the vernal equinox, and assigns an inclination of 4°. He found that as the observer moved to the north or south the axis of the light appeared to be displaced in the direction of the motion, which is the opposite of the effect due to parallax, but in the same sense as the effect of the greater atmospheric absorption of the light on the side nearest the horizon. He also describes the moon as adding to the zodiacal light during her first and last quarters, a result so difficult to explain that it needs confirmation. It is noteworthy that he could see the zodiacal band across the entire sky during the whole of every very clear moonless night in tropical regions.

If we accept the general conclusion already drawn as to the