the transverse vibrations before they reach the belly. This is accomplished by a certain lateral elasticity of the bridge itself, attained by under-cutting the sides so as to allow the upper half of the bridge to oscillate or rock from side to side upon its central trunk; the work done in setting up this oscillation absorbing the transverse vibrations above mentioned.

History.The function of the sound-post is on the one hand mechanical, and on the other acoustical. It serves the purpose of sustaining the greater share of the pressure of the strings, not so much to save the belly from yielding under that pressure, as to enable it to vibrate more freely in its several parts than it could do, if unsupported, under the stresses which would be set up in its substance by that pressure. The chosen position of the post, allowing some freedom of vibration under the bridge, ensures the belly's proper vibrations being directly set up before the impulses are transmitted to the back through the sound-post: this transmission being, as already shown, its principal function. The post also by its contact with both vibrating plates is, as already shown, a governing factor in determining the nodal division of their surfaces, and its position therefore influences fundamentally the related states of vibration of the two plates of the instrument, and the compound oscillations set up in the contained body of air. This is an important element in determining the tone character of the instrument. The immediate ancestors of the violins were the viols, which were the principal bowed instruments in use from the end of the 15th to the end of the 17th century, during the latter part of which period they were gradually supplanted by the violins; but the bass viol did not go out of use finally until towards the later part of the 18th century, when the general adoption of the larger pattern of violoncello drove the viol from the field it had occupied so long. The sole survivor of the viol type of instrument, although not itself an original member of the family, is the double bass of the modern orchestra, which retains many of the characteristic features of the viol, notably the flat back, with an oblique slope at the shoulders, the high bridge and deep ribs. Excepting the marine trumpet or bowed monochord, we find in Europe no trace of any large bowed instruments before the appearance of the viols; the bowed instruments of the middle ages being all small enough to be rested on or against the shoulder during performance. The viols probably owe their origin directly to the minnesinger fiddles, which possessed several of the typical features of the violin, as distinct from the guitar family, and were sounded by a bow. These in their turn may be traced to the "guitar fiddle" (q.v.), a bowed instrument of the 13th century, with five strings, the lowest of which was longer than the rest, and was attached to a peg outside the head so as to clear the nut and finger-board, thus providing a fixed bass, or bourdon. This instrument had incurved sides, forming a waist to facilitate the use of the bow, and was larger than its descendants the fiddles and violins. None of these earlier instruments can have had a deeper compass than a boy's voice. The use of the fidel in the hands of the troubadours, to accompany the adult male voice, may explain the attempts which we trace in the 13th century to lengthen the oval form of the instrument. The parentage of the fiddle family may safely be ascribed to the rebec, a bowed instrument of the early middle ages, with two or three strings stretched over a low bridge, and a pear-shaped body pierced with sound-holes, having no separate neck, but narrowed at the upper end to provide a finger-board, and (judging by pictorial representations, for no actual example is known) surmounted by a carved head holding the pegs, in a manner similar to that of the violin. The bow, which was short and clumsy, had a considerable curvature. So far it is justifiable to trace back the descent of the violin in a direct line; but the earlier ancestry of this family is largely a matter of speculation. The best authorities are agreed that stringed instruments in general are mainly of Asiatic origin, and there is evidence of the mention of bowed instruments in Sanskrit documents of great antiquity. Too much genealogical importance has been attached by some writers to similarities in form and construction between the bowed and plucked instruments of ancient times. They probably developed to a great extent independently; and the bow is of too great and undoubted antiquity to be regarded as a development of the plectrum or other devices for agitating the plucked string. The two classes of instrument no doubt were under mutual obligations from time to time in their development. Thus the stringing of the viols was partly adapted from that of the lute; and the form of the modern Spanish guitar was probably derived from that of the fidel.

The Italian and Spanish forms (ribeba, rabe) of the French name rebec suggest etymologically a relationship, which seems to find confirmation in the striking similarity of general appearance between that instrument and the Persian rebab, mentioned in the 12th century, and used by the Arabs in a primitive form to this day. The British crwth, which has been claimed by some writers as a progenitor of the violin, was primarily a plucked instrument, and cannot be accepted as in the direct line of ancestry of the viols.

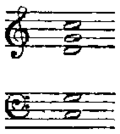

The viol was made in three main kinds—discant, tenor and bass—answering to the cantus, medius and bassus of vocal music. Each of these three kinds admitted of some variation in dimensions, especially the bass, of which three distinct sizes ultimately came to be made—(1) the largest, called the concert bass viol; (2) the division or solo bass viol, usually known by its Italian name of viola da gamba; and (3) the lyra or tablature bass viol. The normal tuning of the viols, as laid down in the earliest books, was adapted from the lute to the bass viol, and repeated in higher intervals in the rest. The fundamental idea, as in the lute, was that the outermost strings should be two octaves apart—hence the intervals of fourths with a third in the middle. The highest, or discant viol, is not a treble but an alto Discant viol.instrument, the three viols answering to the three male voices. As a treble instrument, not only for street and dance music, but in orchestras, the rebec or geige did duty until the invention of the violin, and long afterwards. The discant viol first became a real treble instrument in the hands of the French makers, who converted it into the quinton.

| Discant Viol. | Tenor Viol. | Viol da Gamba. (Bass Viol.) |

|

|

|

The earliest use of the viols was to double the parts of vocal concerted music; they were next employed in special compositions Development of the viols.for the viol trio written in the same compass. Many such works in the form of "fantasies" or "fancies," and preludes with suites in dance form, by the masters of the end of the 16th and 17th centuries, exist in manuscript; a set by Orlando Gibbons, which are good specimens, has been published by the English Musical Antiquarian Society. Later, the viols, especially the bass, were employed as solo instruments, the methods of composition and execution being based on those of the lute. Most lute music is in fact equally adapted for the bass viol, and vice versa. In the 17th century, when the violin was coming into general use, constructive innovations began which resulted in the abandonment of the trio of pure six-stringed viols. Instruments which show these innovations are the quinton and the viola d'amore. The first-mentioned is of a type intermediate between the viol and the violin. In the case of the discant and tenor viol the lowest string, which was probably found to be of little use, was abandoned, and the pressure on the bass side of the belly thus considerably lightened. The five strings were then spread out, as it were, to the compass of the six, so as to retain the fundamental principle of the outer strings being two octaves apart. This was effected by tuning the lower half of the instrument in fifths, as in the violin, and the upper half in fourths. This innovation altered the tuning of the treble and tenor viols, thus—

| Treble Quinton. | Quinte or Tenor Quinton. |

|

|

One half of the instrument was therefore tuned like a viol, the other half as in a violin, the middle string forming the division. The tenor viol thus improved was called in France the quinte, and the treble corresponding to it the quinton. From the numerous specimens which survive it must have been a popular instrument, as it is undoubtedly a substantially excellent one. The