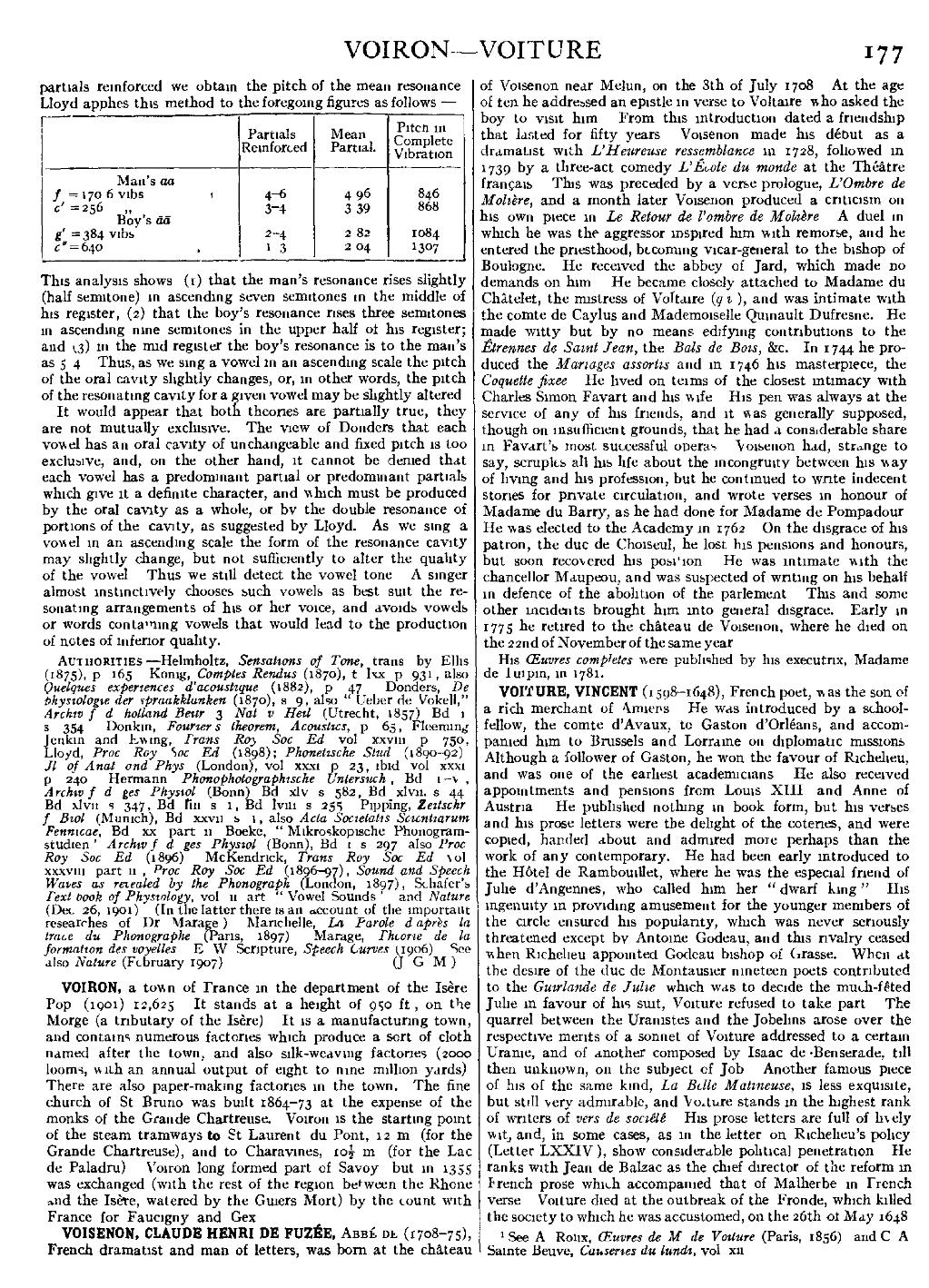

partials reinforced we obtain the pitch of the mean resonance. Lloyd applies this method to the foregoing figures as follows:—

| Partials Reinforced. |

Mean Partial. |

Pitch in Complete Vibration. | |

| Man’s āā. | |||

| f = 170.6 vibs. | 4–6 | 4.96 | 846 |

| c′ = 256 6 vibs.„ | 3–4 | 3.39 | 868 |

| Boy’s āā. | |||

| g′ = 384 vibs. | 2–4 | 2.82 | 1084 |

| c″ = 640 | 1–3 | 2.04 | 1307 |

This analysis shows: (1) that the man’s resonance rises slightly (half semitone) in ascending seven semitones in the middle of his register, (2) that the boy’s resonance rises three semitones in ascending nine semitones in the upper half of his register; and (3) in the mid register the boy’s resonance is to the man’s as 5:4. Thus, as we sing a vowel in an ascending scale the pitch of the oral cavity slightly changes, or, in other words, the pitch of the resonating cavity for a given vowel may be slightly altered.

It would appear that both theories are partially true, they are not mutually exclusive. The view of Donders that each vowel has an oral cavity of unchangeable and fixed pitch is too exclusive, and, on the other hand, it cannot be denied that each vowel has a predominant partial or predominant partials which give it a definite character, and which must be produced by the oral cavity as a whole, or by the double resonance of portions of the cavity, as suggested by Lloyd. As we sing a vowel in an ascending scale the form of the resonance cavity may slightly change, but not sufficiently to alter the quality of the vowel. Thus we still detect the vowel tone. A singer almost instinctively chooses such vowels as best suit the resonating arrangements of his or her voice, and avoids vowels or words containing vowels that would lead to the production of notes of inferior quality.

Authorities.—Helmholtz, Sensations of Tone, trans. by Ellis (1875), p. 165. König, Comptes Rendus (1870), t. lxx p. 931; also Quelques expériences d’acoustique (1882), p. 47. Donders, De physiologue der spraakklanken (1870), s. 9; also “Ueber de Vokell,” Archiv f. d. holländ Beitr. 3. Nat. v. Heil. (Utrecht, 1857), Bd. i. s. 354. Donkin, Fourier’s theorem, Acoustics, p. 65; Fleeming, Jenkin and Ewing, Trans. Roy. Soc. Ed. vol. xxviii. p. 750, Lloyd, Proc. Roy. Soc. Ed. (1898); Phonetische Stud. (1890–92); Jl. of Anat. and Phys. (London), vol. xxxi. p. 23, ibid, vol xxxi. p. 240. Hermann, Phonophotographische Untersuch., Bd. i.–v.; Archiv f. d. ges. Physiol. (Bonn), Bd. xlv. s. 582; Bd. xlvii. s. 44, Bd. xlvii. s. 347; Bd. liii. s. 1; Bd. lviii. s. 255. Pipping, Zeitschr. f. Biol. (Munich), Bd. xxvii. s. 1; also Acta Societatis Scientiarum Fennicae, Bd. xx. part ii. Boeke, “Mikroskopische Phonogramstudien,” Archiv f. d. ges. Physiol. (Bonn), Bd. 1. s. 297; also Proc. Roy. Soc. Ed. (1896). McKendrick, Trans. Roy. Soc. Ed. vol. xxxviii. part ii.; Proc. Roy. Soc. Ed. (1896–97); Sound and Speech Waves as revealed by the Phonograph (London, 1897); Schäfer’s Text-book of Physiology, vol. ii. art. “Vowel Sounds”, and Nature (Dec. 26, 1901). (In the latter there is an account of the important researches of Dr Marage.) Marichelle, La Parole d'après la tracé du Phonographe (Paris, 1897). Marage, Théorie de la formation des voyelles. E. W. Scripture, Speech Curves (1906). See also Nature (February 1907). (J. G. M.)

VOIRON, a town of France in the department of the Isère. Pop. (1901) 12,625. It stands at a height of 950 ft, on the Morge (a tributary of the Isère). It is a manufacturing town, and contains numerous factories which produce a sort of cloth named after the town, and also silk-weaving factories (2000 looms, with an annual output of eight to nine million yards). There are also paper-making factories in the town. The fine church of St Bruno was built 1864–73 at the expense of the monks of the Grande Chartreuse. Voiron is the starting-point of the steam tramways to St Laurent du Pont, 12 m. (for the Grande Chartreuse), and to Charavines, 10½ m. (for the Lac de Paladru). Voiron long formed part of Savoy, but in 1355 was exchanged (with the rest of the region between the Rhone and the Isère, watered by the Guiers Mort) by the count with France for Faucigny and Gex.

VOISENON, CLAUDE HENRI DE FUZÉE, Abbé de (1708–75), French dramatist and man of letters, was born at the château of Voisenon near Melun, on the 8th of July 1708. At the age of ten he addressed an epistle in verse to Voltaire, who asked the boy to visit him. From this introduction dated a friendship that lasted for fifty years. Voisenon made his début as a dramatist with L’Heureuse ressemblance in 1728, followed in 1739 by a three-act comedy l’École du monde at the Théâtre français. This was preceded by a verse prologue, l’Ombre de Molière, and a month later Voisenon produced a criticism on his own piece in Le Retour de l’ombre de Molière. A duel in which he was the aggressor inspired him with remorse, and he entered the priesthood, becoming vicar-general to the bishop of Boulogne. He received the abbey of Jard, which made no demands on him. He became closely attached to Madame du Châtelet, the mistress of Voltaire (q.v), and was intimate with the comte de Caylus and Mademoiselle Quinault Dufresne. He made witty but by no means edifying contributions to the Étrennes de Saint-Jean, the Bals da Bois, &c. In 1744 he produced the Mariages assortis and in 1746 his masterpiece, the Coquette fixée. He lived on terms of the closest intimacy with Charles Simon Favart and his wife. His pen was always at the service of any of his friends, and it was generally supposed, though on insufficient grounds, that he had a considerable share in Favart’s most successful operas. Voisenon had, strange to say, scruples all his life about the incongruity between his way of living and his profession, but he continued to write indecent stories for private circulation, and wrote verses in honour of Madame du Barry, as he had done for Madame de Pompadour. He was elected to the Academy in 1762. On the disgrace of his patron, the duc de Choiseul, he lost his pensions and honours, but soon recovered his position. He was intimate with the chancellor Maupeou, and was suspected of writing on his behalf in defence of the abolition of the parlement. This and some other incidents brought him into general disgrace. Early in 1775 he retired to the château de Voisenon, where he died on the 22nd of November of the same year.

His Œuvres complètes were published by his executrix, Madame de Turpin, in 1781.

VOITURE, VINCENT (1598–1648), French poet, was the son of a rich merchant of Amiens. He was introduced by a school-fellow, the comte d’Avaux, to Gaston d’Orléans, and accompanied him to Brussels and Lorraine on diplomatic missions. Although a follower of Gaston, he won the favour of Richelieu, and was one of the earliest academicians. He also received appointments and pensions from Louis XIII. and Anne of Austria. He published nothing in book form, but his verses and his prose letters were the delight of the coteries, and were copied, handed about and admired more perhaps than the work of any contemporary. He had been early introduced to the Hôtel de Rambouillet, where he was the especial friend of Julie d’Angennes, who called him her “dwarf king.” His ingenuity in providing amusement for the younger members of the circle ensured his popularity, which was never seriously threatened except by Antoine Godeau, and this rivalry ceased when Richelieu appointed Godeau bishop of Grasse. When at the desire of the duc de Montausier nineteen poets contributed to the Guirlande da Julie, which was to decide the much-fêted Julie in favour of his suit, Voiture refused to take part. The quarrel between the Uranistes and the Jobelins arose over the respective merits of a sonnet of Voiture addressed to a certain Uranie, and of another composed by Isaac de Benserade, till then unknown, on the subject of Job. Another famous piece of his of the same kind, La Belle Matineuse, is less exquisite, but still very admirable, and Voiture stands in the highest rank of writers of vers de société. His prose letters are full of lively wit, and, in some cases, as in the letter on Richelieu’s policy (Letter LXXIV.), show considerable political penetration. He ranks with Jean de Balzac as the chief director of the reform in French prose which accompanied that of Malherbe in French verse. Voiture died at the outbreak of the Fronde, which killed the society to which he was accustomed, on the 26th of May 1648.

See A. Roux. Œuvres de M. de Voiture (Paris, 1856); and C. A. Sainte-Beuve, Causeries du lundi, vol xii.