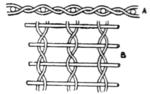

Fig. 16—Compound Fabric.

back weaves, the design, and a transverse section of a compound cloth with two threads of face warp and weft to one of back, and both are stitched together. The circles in the upper and lower lines represent face and back warps respectively, and A, B, C are weft threads placed in the upper and lower textures. Loom-made tapestries and figured repps form another section of Group 2. As compared with true tapestries, the loom-made articles have more limited colour schemes, and their figured effects may be obtained from warp as well as weft, whether interlaced to form a plain face, or left floating more or less loosely. Every weft thread, in passing from selvage to selvage, is taken to the surface where required, the other portions being bound at the back. Some specimens are reversible, others are one-sided, but, however numerous the warps and wefts, only one texture is produced. When an extra warp of fine material is used to bind the wefts firmly together a plain or twill weave shows on both sides. If a single warp is employed, two or more wefts form the figure, and the warp seldom floats upon the surface. Where warps do assist to form figure it rarely happens that more than three can be used without overcrowding the reed. Fig. 17 gives the design, and a transverse section of a reversible tapestry in four colours, two of which are warps and two wefts. If either warp or weft is on the surface, corresponding threads are beneath. The bent lines represent weft and the circles warp. Figured repps differ

Fig. 17—Tapestry with Two Warps and Two Wefts.

from plain ones in having threads of one. or more than one, thick warp floated over thick and thin weft alike; or, in having several differently coloured warps from which a fixed number of threads are lifted over each thick weft thread; the face of the texture is then uniform, and the figure is due to colour.

Group 3. Piled Fabrics.—In all methods of weaving hitherto dealt with the warp and weft threads have been laid in longitudinal and transverse parallel lines. In piled fabrics, however, portions of the weft or warp assume a vertical position. If the former there are

two series of weft threads, one being intersected with the warp to form a firm ground texture, the other being bound into the ground at regular intervals, as in the design and transverse section of a velveteen, fig. 18; the circles and waved lines form plain cloth, and the loose thread A is a pile pick. After leaving the loom all threads A are cut by pushing a knife lengthwise between the plain cloth and the pile. As each pick is severed both pieces rise vertically and the fibres open out as at B. Since the pile threads are from two to six times as numerous as those of the ground, and rise from an immense number of places, a uniform brush-like surface is formed. Raised figures are produced by carrying the threads A beneath the ground cloth, where no figure is required, so that the knife shall only cut those portions of the pile weft that remain on the surface. The effect upon the face varies with the distribution of the binding points, and the length of pile is determined by the distance separating one point from another.

Fig. 18—Velveteen.

Chenille.— When chenille is used in the construction of figured weft-pile fabrics, it is necessary to employ two weaving operations, namely, one to furnish the chenille, the other to place it in the final fabric. Chenille is made from groups of warp threads that are separated from each other by considerable intervals; then, multicoloured wefts are passed from side to side in accordance with a predetermined scheme. This fabric is next cut midway between the groups of warp into longitudinal strips, and, if reversible fabrics such as table-covers and curtains are required, each strip is twisted axially until the protruding ends of weft radiate from the core of warp, and form a cylinder of pile. In the second weaving this chenille is folded backward and forward in a second warp to lay the colours in their appointed places and pile projects on both sides of the fabric. If chenille is intended for carpets, the ends of pile weft are bent in one direction, and then woven into the upper surface of a strong ground texture.

Warp-piled Fabrics have at least two series of warp threads to one of weft, and are more varied in structure than weft-piled fabrics, because they may be either plain or figured, and have their surfaces cut, looped or both.

Velvets and Plushes are woven single and double. In the former case both ground and pile warps are intersected with the weft, but at intervals of two or three picks the pile threads are lifted over a wire, which is subsequently withdrawn; if the wire is furnished with a knife at its outer extremity, in withdrawing it the pile threads are cut, but if the wire is pointed a line of loops remains, as in terry velvet. Fig. 19 is the design, and two longitudinal sections of a Utrecht velvet. The circles at A are weft threads, and the bent line is a pile thread, part of which is shown cut, another part being looped over a wire. At B the circles are repeated to show how the ground warp intersects the weft.

Double Plushes consist of two distinct ground textures which are kept far enough apart to ensure the requisite length of pile. As weaving proceeds the pile threads are interlaced with each series of weft threads, and passed from one to the other. The uniting pile material is next severed midway between the upper and lower textures, and two equal fabrics result. Fig. 20 gives three longitudinal

|

|

| Fig. 19—Utrecht Velvet. | Fig. 20—Double Plush. |

sections of a double pile fabric. The circles A, .B are weft threads in the upper and lower fabrics respectively; the lines that interlace with these wefts are pile warp threads which pass vertically from one fabric to the other. At C, D the circles are repeated to show how the ground warps intersect the wefts, and at E the arrows indicate the cutting point.

Figured Warp-pile Fabrics are made with regular and irregular cut and looped surfaces. If regular, the effect is due to colour, and this again may be accomplished in various ways, such as (a) by knotting tufts of coloured th reads u pon a warp, as in Eastern carpets; (b) by printing a fabric after it leaves the loom; (c) by printing each pile thread before placing it in a loom, so tha: a pattern shall be formed simultaneously with a pile surface, as in tapestry carpets; (d) by providing several sets of pile threads, no two of which are similar in colour; then, if five sets are available, one-fifth of all the pile warp must be lifted over each wire, but any one of five colours may be selected at any place, as in Brussels and Wilton carpets. Fig. 21 is the design, and a longitudinal section of a Brussels carpet. The circles represent two tiers of weft, and the lines of pile threads, when not lifted over a wire to form loops, are laid between the wefts; the ground warp interlaces with the weft to bind the whole together. When the surface of a piled fabric is irregular, also when cut and looped pile are used in combination, design is no longer dependent upon colour, for in the former case pile threads are only lifted over wires where required, at other places a flat texture is formed. In the latter case the entire surface of a fabric is covered with pile, but if the figure is cut and the ground looped the pattern will be distinct.

Fig. 21—Brussels Carpet.

Group 4. Crossed Weaving.—This group includes all fabrics in which the warp threads inter twist amongst themselves to give intermediate effects between ordinary weaving and lace, as in gauzes. Also those in which some warp threads are laid transversely in a piece to imitate embroidery, as in lappets.

Plain Gauze embodies the principles that underlie the construction of all crossed woven textiles. In these fabrics the twisting of two warp threads together leaves large interstices between both warp and weft. But although light and open in texture, gauze fabrics are the firmest that can be made from a given quantity and quality of material. One warp thread from each pair is made to cross the other at every pick, to the right and to the left alternately, therefore the same threads are above every pick, but since in crossing from side to side they pass below the remaining threads, all are bound securely together, as in fig. 22, where A is a longitudinal section and B a plan of gauze.

Leno is a muslin composed of an odd number of picks of a plain weave followed by one pick of gauze. In texture it is heavier than gauze, and the cracks are farther apart transversely.

Fancy Gauze may be made in many ways, such as (a) by using crossing threads that differ in colour or count from the remaining threads, provided they are subjected to slight tensile strain; (b) by causing some to twist to the right, others to the left simultaneously; (c) by combining gauze with another weave, as plain, twill, satin, brocade or pile; (d) by varying the number of threads that cross, and by causing those threads to entwine several ordinary threads; (e) by passing two or more weft threads into each crossing, and operating any assortment of crossing threads at pleasure.

Fig. 22—Plain Gauze.