series that separate one line of loops from another. At such times

the weft is not beaten home, but a broad crack is formed. So soon

as the reed again moves through its normal space three picks of weft

are simultaneously driven home, thus closing the gap, and causing

part of the pile to loop upward, the remainder downward. The

system is available for plain and figured effects.

Gauze Textures are woven in looms having a modified shedding

harness, which, at predetermined intervals, draws certain warp

threads crosswise beneath others, and lifts them while crossed.

Also, a pensioning device to slacken the crossed threads and thus

prevent breakages due to excessive strain. At other times the

shedding is normal.

Lappet Looms have a series of needles fixed upright in laths, and placed in a groove cut in the slay, in front of the reed. Each needle carries a thread which does not pass through the reed, hence, by giving the laths an endlong movement of varying extent, and lifting the needles for each pick, their threads are laid crosswise in the web to pattern. (T. W. F.)

From Roth’s Native of Sarawak, by permission of

Truslove and Hanson.

Fig 29—Loom from Sarawak.

Archaeology and Art

The archaeology of shuttle-weaving shows that for ages the use of a loom for weaving plain, as distinct from ornamental or figured textiles, whether of fibres or of spun threads, has been practically universal, whilst the essential points of its construction have been almost uniform in character. An early stage in its development, anterior probably to that when the spinning of threads had been invented, is represented by the loom or frame (see fig. 29) used by a native of Sarawak to make a textile with shreds of grass. As will be seen, the shreds of grass for the warp are divided into groups by a flat sword-shaped implement which serves as the batten (Latin spatha). The shuttle is passed above it, leaving a weft of grass in between the warp; the batten is then moved upwards and compresses the weft into the warp; this method of pressing the weft upwards was usually employed by Egyptian and Greek weavers for their linen textiles of beautiful quality. Fig. 30 gives us an Indian

Fig. 30—Indian Hill Tribesman's Loom.

Hill tribesman weaving with spun threads; but here we find the loom fitted with rudely constructed headles, by which the weaver lifts and lowers alternate ranks of warp threads so that he may throw his shuttle-carried weft across and between them. Besides the headles there is a hanging reed or comb, and between the reeds of it the warp threads are passed and fastened to a roller or cylinder. After throwing his shuttle once or twice backwards and forwards, the weaver pulls the comb towards himself, thereby pressing his weft and warp together, thus making the textile which he gradually winds from time to time on to the roller. This advance in the construction of the loom is also virtually of undateable age; and except for more substantial construction, there is little difference in main principles between it and the medieval loom of fig. 31. With such looms, and by arranging coloured warp threads in a given order and then weaving into them coloured shuttle or weft threads, simple textiles with stripes and chequer patterns could be and were,

Fig 31—Medieval Loom, from a Cut by

Jost Amman; middle of the 16th century.

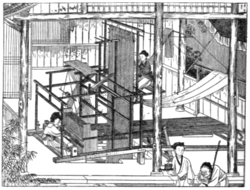

produced; but textiles of complex patterns and textures necessitated the more complicated apparatus that belongs to a later stage in the evolution of the loom. Fig. 32 is from a Chinese drawing, illustrating the description given in a Chinese book published in 1210 on the art of weaving intricate designs. The traditions and records of such figured weavings are far older than the dale of this book. As spun silken threads were brought into use, so the development of looms with increasing numbers of headles and other mechanical facilities for this sort of weaving seems to have started. But as far back as 2690 B.C. the Chinese were the only cultivators of silk,[1] the delicacy and fineness of which must have postulated possibilities in

Fig 32—Chinese Loom for Figured Weaving (Photo).

weaving far beyond those of looms in which grasses, wools and flax were used. It therefore is probably correct to credit the Chinese with being the earlier inventors of looms for weaving figured silks, which in course of time other nations (acquainted only with wool and flax textiles) saw with wonder. At the comparatively modern period of 300 B.C. Chinese dexterity in fine-figured weaving had become matured and was apparently in advance of any other elsewhere. Designs were being woven by the Chinese of the earlier Han Dynasty 206 B.C. as elaborate almost

- ↑ E. Pariset, Histoire de la soie (Paris, 1862).