reservoir dam for storing up water for water-supply or irrigation,

kept purposely lower than the rest of the dam to allow the excess

of water to escape down the valley (see Water-Supply).

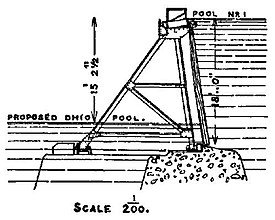

Draw-door Weirs.—The discharge of a river at a weir can be regulated as required and considerably increased in flood-time by introducing a series of openings in the centre of a solid weir, with sluice-gates or panels which slide in grooves at the sides of upright frames or masonry piers erected at convenient intervals apart, and which can be raised or lowered as desired from a foot-bridge.

This arrangement has been provided at several weirs on the Thames,

to afford control of the flood discharge,

Fig. 2.—Mechanism of Lifting-gate,

Richmond. and reduce the extent of the

inundations; the largest of these composite weirs on that river is

at the tidal limit at Teddington, where the two central bays, with a

total length of 24214 ft., are closed by thirty-five draw-doors sliding

between iron frames supporting a foot-bridge, from which the doors

are raised by a winch.[1]

Ordinary draw-doors, sliding in grooves of

moderate size and raised

against a small head of water,

can be readily worked in

spite of the friction of the

sides of the doors against

their supports; but with

large draw-doors and a considerable

head, the friction

of the surfaces in contact

offers a serious impediment

in raising them. This friction

has been greatly reduced

by making the draw-doors,

or sluice-gates, slide

on each side against a vertical

row of free-rollers suspended

by an encircling

chain; and the working

is much facilitated by

counterpoising the doors.

By these arrangements the

large draw-door weir across

the Thames at Richmond, with three spans of 66 ft. closed by

lifting doors, each 12 ft. high and weighing 32 tons, can be fully

opened in seven minutes by two men raising each door from the

arched double foot-bridge (figs. 1, 2 and 3). This weir retains the

river above it at half-tide level, in order to cover the mud-banks

which had been bared at low tide between Richmond and Teddington

by the lowering of the low-water level, owing to the removal of

various obstructions in the river below.

The weir is raised

out of the river as soon as the flood-tide on its lower side has

risen to half-tide level, so as not to impede the flow and ebb

of the tide up to Teddington above that level, and is not lowered

till the tide has fallen again to the same level. In order that

the doors when raised may not impede the view under the arches,

the doors are rotated automatically at the top by grooves at

the sides of the piers, so as to assume a horizontal position and

pass out of sight in the central space between the two foot-ways

(fig. 2). The barrage at the head of the Nile delta, and the

regulating sluices across the Nile at Assiut and Esna in Upper

Egypt below Assuan, are examples of draw-door weirs, with their

numerous openings closed by sluice-gates sliding on free rollers,

which control the discharge of water from the river for irrigation.

Movable Weirs.—There are three main types of movable weirs, namely frame weirs, shutter weirs and drum weirs, which, however, present several variations in their arrangements.

The ordinary form of frame weir consists of a series of iron frames placed across a river end on to the current, between 3 and 4 ft. apart, hinged to a masonry apron on the bed of the river and carrying a foot-bridge along the top, from which the actual barrier, resting against the frames and crossbars at the top and a sill at the bottom, is put into place or removed Frame weir. for closing or opening the weir.

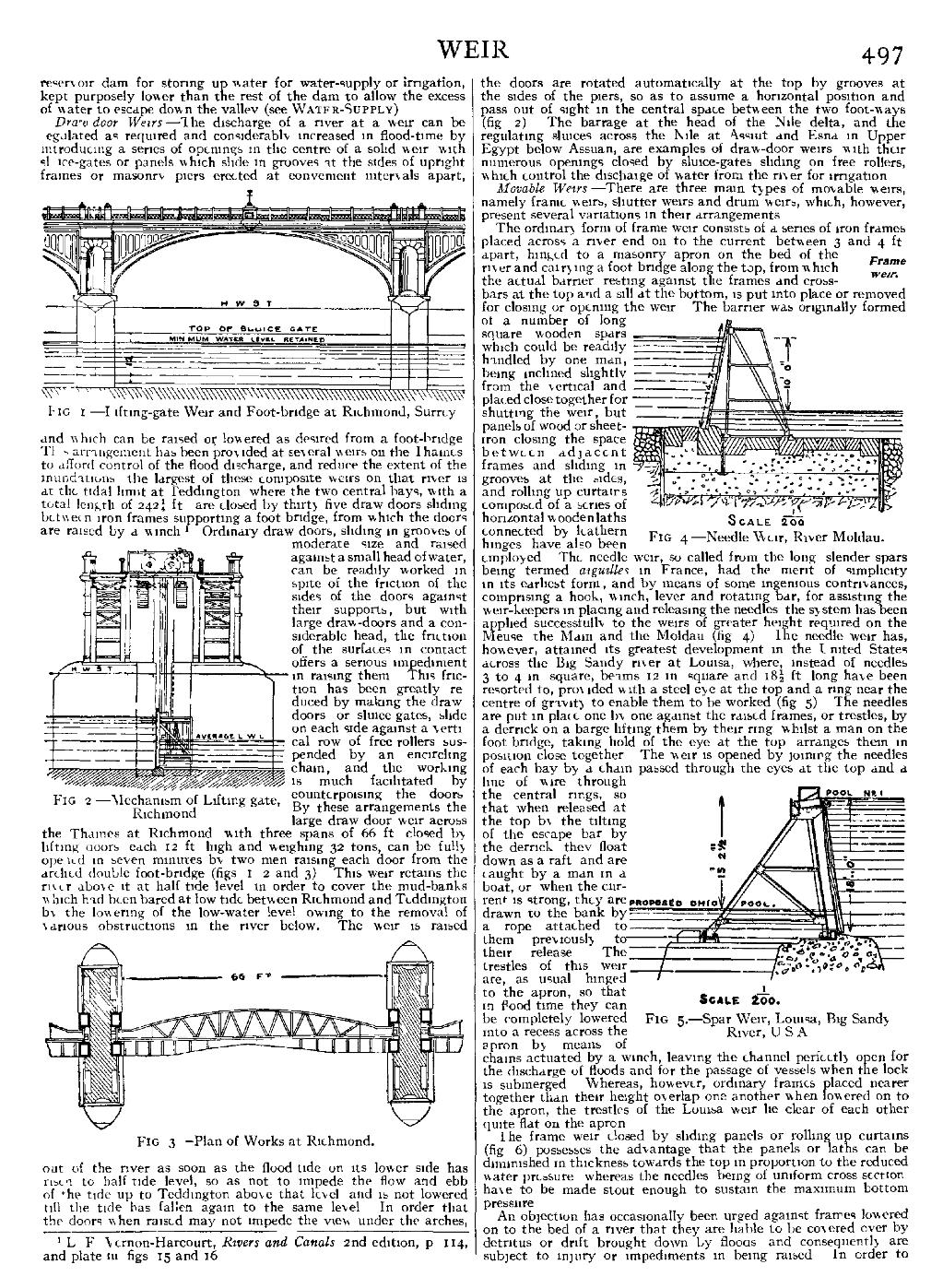

The barrier was originally formed of a number of long square wooden spars which could be readily handled by one man, being inclined slightly from the vertical and placed close together for shutting the weir; but panels of wood or sheet-iron closing the space between adjacent frames and sliding in grooves at the sides, and rolling-up curtains composed of a series of horizontal wooden laths connected by leathern hinges, have also been employed. The needle weir, so called from the long, slender spars being termed aiguilles in France, had the merit of simplicity in its earliest form; and by means of some ingenious contrivances, comprising a hook, winch, lever and rotating bar, for assisting the weir-keepers in placing and releasing the needles, the system has been applied successfully to the weirs of greater height required on the Meuse, the Main and the Moldau (fig. 4). The needle weir has, however, attained its greatest development in the United States across the Big Sandy river at Louisa, where, instead of needles 3 to 4 in. square, beams 12 in. square and 1812 ft. long have been resorted to, provided with a steel eye at the top and a ring near the centre of gravity to enable them to be worked (fig. 5). The needles are put in place one by one against the raised frames, or trestles, by a derrick on a barge lifting them by their ring, whilst a man on the foot-bridge, taking hold of the eye at the top, arranges them in position close together.

The weir is opened by joining the needles of each bay by a chain passed through the eyes at the top and a line of wire through the central rings, so that when released at the top by the tilting of the escape bar by the derrick, they float down as a raft, and are caught by a man in a boat, or, when the current is strong, they are drawn to the bank by a rope attached to them previously to their release. The trestles of this weir are, as usual, hinged to the apron, so that in flood-time they can be completely lowered into a recess across the apron by means of chains actuated by a winch, leaving the channel perfectly open for the discharge of floods and for the passage of vessels when the lock is submerged. Whereas, however, ordinary frames placed nearer together than their height overlap one another when lowered on to the apron, the trestles of the Louisa weir lie clear of each other quite flat on the apron.

The frame weir closed by sliding panels or rolling-up curtains (fig. 6) possesses the advantage that the panels or laths can be diminished in thickness towards the top in proportion to the reduced water-pressure; whereas the needles, being of uniform cross-section, have to be made stout enough to sustain the maximum bottom pressure.

An objection has occasionally been urged against frames lowered on to the bed of a river that they are liable to be covered over by detritus or drift brought down by floods, and consequently are subject to injury or impediments in being raised.

In order to- ↑ L. F. Vernon-Harcourt, Rivers and Canals, 2nd edition, p. 114, and plate iii. figs. 15 and 16.