cotyledons with inconspicuous flowers. Singularly enough, the sexual system of Linnaeus (1735) served to mark off more distinctly the true grasses from these allies, since very nearly all of the former then known fell under his Triandria Digyniii, whilst the latter found themselves under other of his artificial classes and orders.

I. Structure.—The general type of true grasses is familiar in the cultivated cereals of temperate climates— wheat, barley, rye, oats, and in the smaller plants which make up our pastures and meadows and form a principal factor of the turf of natural downs. Less familiar are the grains of warmer climes—rice, maize, millet, and sorgho, or the sugar cane. Still further removed are the bamboos of India and America, the columnar stems of which reach to the height of forest trees. All are, however, formed on a common type, which we proceed to examine.

Root.—Most cereals and many other grasses are annual, and possess a tuft of very numerous slender root-fibres, much branched, and of great length. The greater part of the order are of longer duration, and have the roots also fibrous, but fewer, thicker, and less branched. In such cases they are very generally given off from just above each node (often in a circle) of the lower part of the stem or rhizome, perforating the leaf-sheaths. In some bamboos they are very numerous from the lower nodes of the erect culms, and pass downwards to the soil around them, whilst those from the upper nodes shrivel up and form circles of spiny fibres.

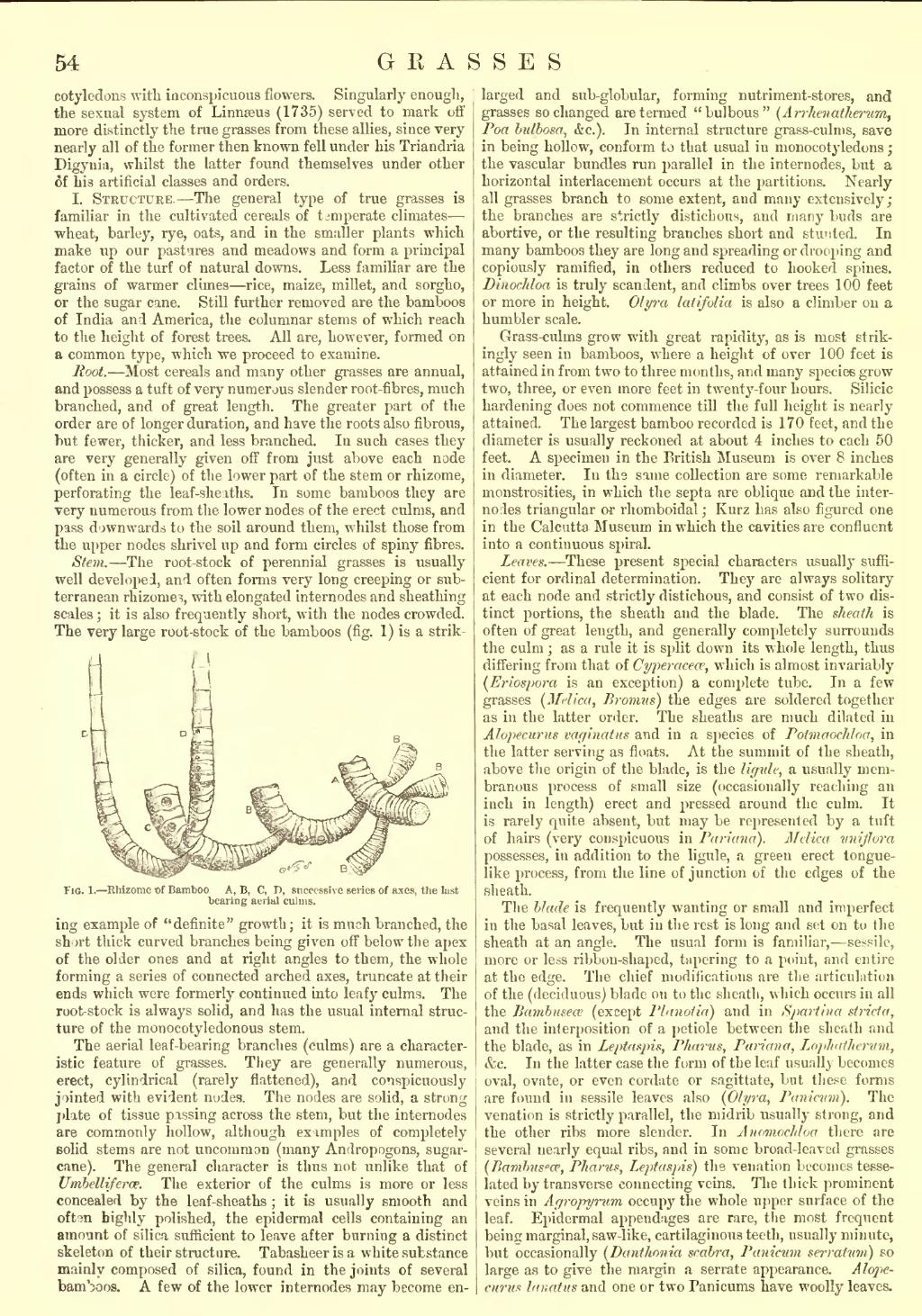

Stem.—The root-stock of perennial grasses is usually well developed, and often forms very long creeping or sub terranean rhizomes, with elongated internodes and sheathing scales ; it is also frequently short, with the nodes crowded. The very large root-stock of the bamboos (fig. 1) is a striking

Fig. 1.—Rhizome of BambooA, B, C, D, successive series of axes, the last bearing aerial culms.

example of "definite" growth ; it is much branched, the short thick curved branches being given off below the apex of the older ones and at right angles to them, the whole forming a series of connected arched axes, truncate at their ends which were formerly continued into leafy culms. The root-stock is always solid, and has the usual internal struc ture of the monocotyledonous stem. The aerial leaf-bearing branches (culms) are a character istic feature of grasses. They are generally numerous, erect, cylindrical (rarely flattened), and conspicuously jointed with evident nudes. The nodes are solid, a strong plate of tissue passing across the stem, but the internodes are commonly hollow, although examples of completely solid stems are not uncommon (many Andropogons, sugar cane). The general character is thus not unlike that of Umbelliferce. The exterior of the culms is more or less concealed by the leaf-sheaths ; it is usually smooth and of tan highly polished, the epidermal cells containing an amount of silica sufficient to leave after burning a distinct skeleton of their structure. Tabasheerisa white substance mainly composed of silica, found in the joints of several bamboos. A few of the lower internodes may become en larged and sub-globular, forming nutriment-stores, and grasses so changed are termed "bulbous" (Arrhenatherum, Poa bulbosa, <fcc.). In internal structure grass-culms, save in being hollow, conform to that usual in monocotyledons ; the vascular bundles run parallel in the internodes, but a horizontal interlacement occurs at the partitions. Nearly all grasses branch to some extent, and many extensively; the branches are strictly distichous, and many buds are abortive, or the resulting branches short and stunted. In many bamboos they are long and spreading or drooping and copiously ramified, in others reduced to hooked spines. Dinochloa is truly scandent, and climbs over trees 100 feet or more in height. Olyra latifolia is also a climber on a humbler scale. Grass-culms grow with great rapidity, as is most strik ingly seen in bamboos, where a height of over 100 feet is attained in from two to three months, and many species grow two, three, or even more feet in twenty-four hours. Silicic hardening does not commence till the full height is nearly attained. The largest bamboo recorded is 170 feet, and the diameter is usually reckoned at about 4 inches to each 50 feet. A specimen in the British Museum is over 8 inches in diameter. In the same collection are some remarkable monstrosities, in which the septa are oblique and the inter nodes triangular or rhomboidal ; Kurz has also figured one in the Calcutta Museum in which the cavities are confluent into a continuous spiral.

Leaves.—These present special characters usually suffi cient for ordinal determination. They are always solitary at each node and strictly distichous, and consist of two dis tinct portions, the sheath and the blade. The sheath is often of great length, and generally completely surrounds the culm ; as a rule it is split down its whole length, thus differing from that of Cyperacece, which is almost invariably (Eriospora is an exception) a complete tube. In a few grasses (fifelica, Bromus] the edges are soldered together as in the latter order. The sheaths are much dilated in Alopecurus vaginatus and in a species of Potmaochloa, in the latter serving as floats. At the summit of the sheath, above the origin of the blade, is the liyide, a usually mem branous process of small size (occasionally reaching an inch in length) erect and pressed around the culm. It is rarely quite absent, but may be represented by a tuft of hairs (very conspicuous in Pariana). Melica imiflora possesses, in addition to the ligule, a green erect tongue- like process, from the line of junction of the edges of the sheath.

The blade is frequently wanting or small and imperfect in the basal leaves, but in the rest is long and sot on to the sheath at an angle. The usual form is familiar, sessile, more or less ribbon-shaped, tapering to a point, and entire at the edge. The chief modifications are the articulation of the (deciduous) blade on to the sheath, which occurs in all the Bambusecc (except Planolia) and in Spartina siricfa, and the interposition of a petiole between the sheath and the blade, as in Leptaspis, P/iarus, Pariana, Lophatherinn, &c. In the latter case the form of the leaf usually becomes oval, ovate, or even cordate or sagittate, but these forms are found in sessile leaves also (Olyra, Paniciim}. The venation is strictly parallel, the midrib usually strong, and the other ribs more slender. In Anotnocliloa there are j several nearly equal ribs, and in some broad-leaved grasses

- (fiambns t >a>, Pharus, Leptaspis) the venation becomes tesse-

lated by transverse connecting veins. The thick prominent veins in Agropyrum occupy the whole upper surface of the ! leaf. Epidermal appendages are rare, the most frequent I being marginal, saw-like, cartilaginous teeth, usually minute, but occasionally (Danthonia scabra, Panicum serratnm) so large as to give the margin a serrate appearance. Alope

curus lanatns and one or two Panicums have woolly leaves.