HIPPEL, Theodor Gottlieb von (1741–1796), a German author, known chiefly as a humorist, was born on the 31st January 1741, at Gerdauen in East Prussia, where his father was rector of a school. In his sixteenth year he went to Konigsberg to study theology ; but through the influence of the Dutch councillor of justice, Woyt, he was induced to devote himself to jurisprudence. A Russian lieutenant, Von Keyser, whose acquaintance he made in Konigsberg, took him in 1760 to St Petersburg, where he might have had a brilliant career had not his love for his country made it impossible for him to live away from it. Returning to Konigsberg he became a tutor in a private family ; but, falling in love with a young lady of high position, he, as the readiest means of enabling him to marry her, gave up his tutorship and devoted himself with en thusiasm to legal studies. He was successful in his pro fession, passing from one grade to another, until in 1780 he was appointed burgomaster and director of police in Konigsberg, and in 1786 privy councillor of war and president of the town ; as be rose in the world, how ever, his inclination for matrimony vanished, and the lady who had stimulated his ambition was forgotten. To write books in his country house near Konigsberg was his favourite amusement, and some of them have still a certain popularity. Perhaps the best known is his Ueber die Ehe (Concerning Marriage). He has also works on The Social Improvement of Woman, and on Female Education. Another curious book of his is Lebensldufe nach aufsteigender Linie, nebst Beilagen A, B, C (Careers according to an ascending line, with supple ments A, B, C). His name is attached to several political writings of a satirical turn, and he was the author of a comedy Der Mann nach der U/tr, which was fortunate enough to win the applause of Lessing. Hippel was a friend of Kant, who admired his ingenuity and resource in forming and executing plans. Before the publication of Kant s Kritik, Hippel was made familiar with its main conclusions, and in his Lebensldufe he did his utmost to prepare the way for their reception. In nearly all his writings he had a serious purpose, but disliking a cold, systematic style, he communicated his ideas in what he intended to be a light and witty form. Much of his wit is rather crude, but he gave sufficient evidence of a lively fancy to justify his success as an author. His private character presented some curious contrasts. He shared the enthusiasm of his age for passionate friendships, but none of his friends were treated with confidence ; endowed with a clear and penetrating intellect, he had a strong tendency to superstition ; he seemed to have generous sympathies, yet his conduct was often hard and selfish; and although he incessantly praised simplicity of life, no one could be more fond of pomp and show. He died on the 23d April 1796, leaving a considerable fortune. In 1827–38 a collected edition of his works in 14 vols. was issued at Berlin.

HIPPO. See Bône.

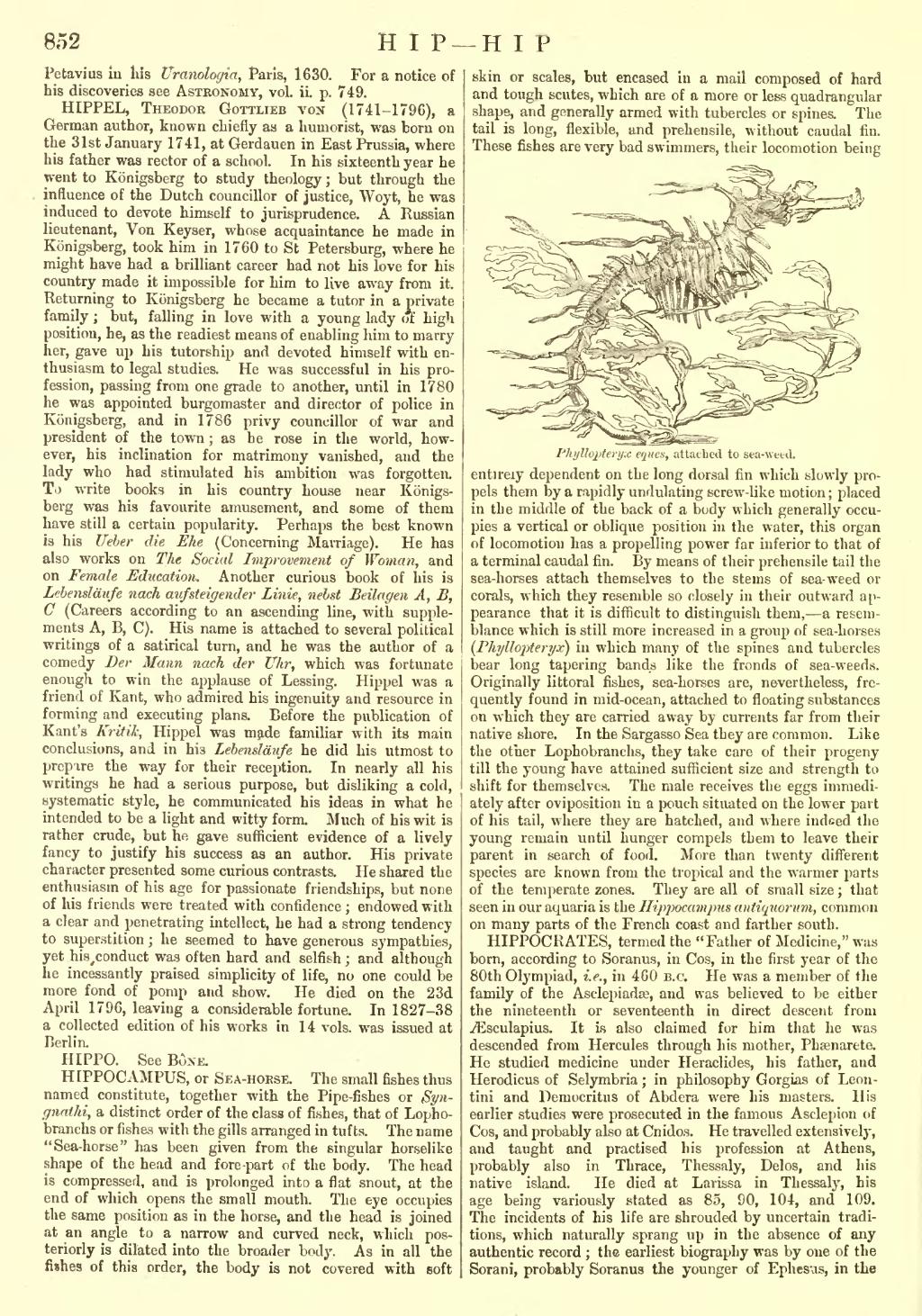

HIPPOCAMPUS, or Sea-Horse. The small fishes thus named constitute, together with the Pipe-fishes or Syngnalhi, a distinct order of the class of fishes, that of Lophobranchs or fishes with the gills arranged in tufts. The name "Sea-horse" has been given from the singular horselike shape of the head and fore-part of the body. The head is compressed, and is prolonged into a flat snout, at the end of which opens the small mouth. The eye occupies the same position as in the horse, and the head is joined at an angle to a narrow and curved neck, which posteriorly is dilated into the broader body. As in all the fishes of this order, the body is not covered with soft skin or scales, but encased in a mail composed of hard and tough scutes, which are of a more or less quadrangular shape, and generally armed with tubercles or spines. The tail is long, flexible, and prehensile, without caudal fin. These fishes are very bad swimmers, their locomotion being entirely dependent on the long dorsal fin which slowly pro pels them by a rapidly undulating screw-like motion; placed in the middle of the back of a body which generally occu pies a vertical or oblique position in the water, this organ of locomotion has a propelling power far inferior to that of a terminal caudal fin. By means of their prehensile tail the sea-horses attach themselves to the sterns of sea-weed or corals, which they resemble so closely in their outward ap pearance that it is difficult to distinguish them,—a resemblance which is still more increased in a group of sea-horses (Phyllopteryx) in which many of the spines and tubercles bear long tapering bands like the fronds of sea-weeds. Originally littoral fishes, sea-horses are, nevertheless, fre- quently found in mid-ocean, attached to floating substances on which they are carried away by currents far from their native shore. In the Sargasso Sea they are common. Like the other Lophobranchs, they take care of their progeny till the young have attained sufficient size and strength to shift for themselves. The male receives the eggs immediately after oviposition in a pouch situated on the lower part of his tail, where they are hatched, and where indeed the young remain until hunger compels them to leave their parent in search of food. More than twenty different species are known from the tropical and the warmer parts of the temperate zones. They are all of small size ; that seen in our aquaria is the Hippocampus anti-quorum, common on many parts of the French coast and farther south.

An image should appear at this position in the text. To use the entire page scan as a placeholder, edit this page and replace "{{missing image}}" with "{{raw image|Encyclopædia Britannica, Ninth Edition, v. 11.djvu/892}}". Otherwise, if you are able to provide the image then please do so. For guidance, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images. |

[ text ], attached to sea-weed.

born, according to Soranus, in Cos, in the first year of the 80th Olympiad, i.e., in 460 b.c. He was a member of the family of the Asclepiadae, and was believed to be either the nineteenth or seventeenth in direct descent from yEsculapius. It is also claimed for him that he was descended from Hercules through his mother, Phsenarete. He studied medicine under Heraclides, his father, and Herodicus of Selymbria ; in philosophy Gorgias of Leontini and Democritus of Abdera were his masters. His earlier studies were prosecuted in the famous Asclepion of Cos, and probably also at Cnidos. He travelled extensively, and taught and practised his profession at Athens, probably also in Thrace, Thessaly, Delos, and his native island. He died at Larissa in Thessaly, his age being variously stated as 85, 90, 104, and 109. The incidents of his life are shrouded by uncertain traditions, which naturally sprang up in the absence of any authentic record ; the earliest biography was by one of the

Sorani, probably Soranus the younger of Ephesus, in the