9 inches and upwards. The Chinese plant is hardy, and capable of thriving under many different conditions of climate and situation; while the indigenous plant is tender and difficult of cultivation, requiring for its success a close, hot, moist, and equable climate. The characteristic venation of the leaf of the Chinese tea-plant is delineated in fig. 2. In minute structure the leaf presents highly characteristic appearances.

Fig.2.—Tea-Leaf—full size.

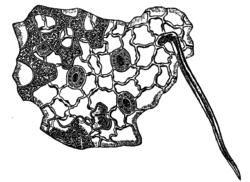

The under side of the young leaf is densely covered with fine one-celled thick-walled hairs, about 1 mm. in length and ·015 mm. in thickness. These hairs entirely disappear with increasing age. The structure of the epidermis of the under side of the leaf, with its contorted cells, is represented ( 160) in fig. 3. A further characteristic feature of the cellular structure of the tea-leaf is the abundance, especially in grown leaves, of large, branching, thick-walled, smooth cells (idioblasts), which, although they occur in other leaves, are not found in such as are likely to be confounded with or substituted for tea. The minute structure of the leaf in section is illustrated in fig. 4.

Fig. 3.—Epidermis of Tea-Leaf (under side) x 160.

Range of growth.The cultivated varieties of tea, being comparatively hardy, possess an adaptability to climate excelled among food plants only by the wheat. The limits of actual tea- cultivation extend from 39° N. lat. in Japan, through the tropics, to Java, Australia, Natal, and Brazil in the southern hemisphere. The tea-plant will even live in the open air in the south of England, and withstand some amount of frost, when it receives sufficient summer heat to harden its wood. But comparatively few regions are suited for practical tea-growing.

Fig. 4.-Section through Tea-Lea.

Climate and soil. A rich and exuberant growth of the plants is a first essential of successful tea cultivation. This is only obtainable in warm, moist, and comparatively equable climates, where rains are frequent and copious. The climate indeed which favours tropical profusion of jungle growth—still steaming heat—is that most favourable for the cultivation of tea, and such climate, unfortunately, is most prejudicial to the health of Europeans. It was formerly supposed that comparatively temperate latitudes and steep sloping ground afforded the most favourable situations for tea-planting, and much of the disaster which attended the early stages of the tea enterprise in India is traceable to this erroneous conception. Tea thrives best in light friable soils of good depth, through which water percolates freely, the plant being specially impatient of marshy situations and stagnant water Undulating well-watered tracts, where the rain escapes freely, yet without washing away the soil, are the most valuable for tea gardens. As a matter of fact, many of the Indian plantations are established on hill-sides, after the example of known districts in China, where hill slopes and odd corners are commonly occupied with tea-plants.

History.According to Chinese legend, the virtues of tea (cha, pronounced in the Amoy dialect té, whence the English name) were discovered by the mythical emperor Chinnung, 2737 B.C., to whom all agricultural and medicinal knowledge is traced. It is doubtfully referred to in the book of ancient poems edited by Confucius, all of which are previous in date to 550 B.C. A tradition exists in China that a knowledge of tea travelled eastward to and in China, having been introduced 543 A.D. by Bodhidharma, an ascetic who came from India on a missionary expedition, but that legend is also mixed with mythical and supernatural details. But it is quite certain, from the historical narrative of Lo Yu, who lived in the Tang dynasty (618–906 A.D.), that tea was already used as a beverage in the 6th century, and that during the 8th century its use had become so common that a tax was levied on its consumption in the 14th year of Tih Tsung (793). The use of tea in China in the middle of the 9th century is known from Arab sources (Reinaud, Relation des Voyages, 1845, p. 40). From China a knowledge of tea was carried into Japan, and there the cultivation was established about the beginning of the 13th century. Seed was brought from China by the priest Miyoye, and planted first in the south island, Kiushiu, whence the cultivation spread northwards till it reached the high limit of 39° N. To the south tea cultivation also spread into Tong-king and Cochin China, but the product in these regions is of inferior quality. Till well into the 19th century it may be said that China and Japan were the only two tea-producing countries, and that the product reached the Western markets only through the narrowest channels and under most oppressive restrictions.

In the year 1826 the Dutch succeeded in establishing tea gardens in Java. At an early period the East India Company of Great Britain, as the principal trade intermediary between China and Europe, became deeply interested in the question of tea cultivation in their Eastern possessions. In 1788 Sir Joseph Banks, at the request of the directors, drew up a memoir on the cultivation of economic plants in Bengal, in which he gave special prominence to tea, pointing out the regions most favourable for its cultivation. About the year 1820 Mr David Scott, one of the Company’s servants, sent to Calcutta from the district of Kuch Behar and Rangpur—the very district indicated by Sir Joseph Banks as favourable for tea-growing—certain leaves, with a statement that they were said to belong to the wild tea-plant. The leaves were submitted to Dr Wallich, Government botanist at Calcutta, who pronounced them to belong to a species of Camellia, and no result followed on Mr Scott’s communication. These very leaves ultimately came into the herbarium of the Linnean Society of London, and have authoritatively been pronounced to belong to the indigenous Assam tea-plant. Dr Wallich’s attribution of this and other specimens