TEAK[1] may justly be called the most valuable of all known timbers. For use in tropical countries it has no equal, and for certain purposes it is preferable to other woods in temperate climates also. Its price is higher than that of any other timber, except mahogany.[2] Great efforts have been made to find substitutes, but no timber has been brought to market in sufficient quantities combining the many valuable qualities which teak possesses.

The first good figure and description of the tree was given by Rheede.[3] The younger Linnæus called it Tectona grandis. It is a large deciduous tree, of the natural order Verbenaceæ, with a tall straight stem, a spreading crown, the branchlets four-sided, with large quadrangular pith. It is a native of the two Indian peninsulas, and is also found in the Philippine Islands, Java, and other islands of the Malay Archipelago.

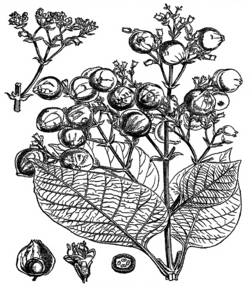

Teak (Tectona grandis).

In India proper its northern limit is 24° 40' on the west side of the Aravalli Hills, and in the centre near Jhansi, in 25° 30' lat. In Burmah it extends to the Mogoung district, in lat. 25° 10'. In Bengal or Assam it is not indigenous, but plantations have been formed in Assam as far as the 27th parallel. In the Punjab it is grown in gardens to the 32d.

Teak requires a tropical climate, and the most important forests are found in the moister districts of India, where during the summer months heavy rains are brought by the south-west monsoon, the winter months being rainless. In the interior of the Indian peninsula, where the mean annual rainfall is less than 30 inches, no teak is found, and it thrives best with a mean annual fall of more than 50 inches. The mean annual temperature which suits it best lies between 75° and 81° Fahr. Near the coast the tree is absent, and the most valuable forests are on low hills up to 3000 feet. It grows on a great variety of soils, but there is one indispensable condition—perfect drainage or a dry subsoil. On level ground, with deep alluvial soil, teak does not often form regularly shaped stems, probably because the subsoil drainage is imperfect.

During the dry season the tree is leafless; in hot localities the leaves fall in January, but in moist places the tree remains green till March. At the end of the dry season, when the first monsoon rains fall, the fresh foliage comes out. The leaves, which stand opposite, are from 1 to 2 feet in length and from 6 to 12 inches in breadth. On coppice shoots the leaves are much larger, and not rarely from 2 to 3 feet long. In shape they somewhat resemble those of the tobacco plant, but their substance is hard and the surface rough. The small white flowers are very numerous, on large erect cross-branched panicles, which terminate the branches. They appear during the rains, generally in July and August, and the seed ripens in January and February. On. the east side of the Indian peninsula, the teak flowers during the rains in October and November. In Java the forests are leafless in September, while during March and April, after the rains have commenced, they are clothed with foliage and the flowers open. During the rainy season the tree is readily recognized at a considerable distance by the whitish flower panicles, which overtop the green foliage, and during the dry season the feathery seed-bearing panicles distinguish it from all other trees. The small oily seeds are enclosed in a hard bony 1-4 celled nut, which is surrounded by a thick covering, consisting of a dense felt of matted hairs. The fruit is enclosed by the enlarged membranous calyx, in appearance like an irregularly plaited or crumpled bladder. The tree seeds freely every year, but its spread by means of self-sown seed is impeded by the forest fires of the dry season, which in India generally occur in March and April, after the seeds have ripened and have partly fallen. Of the seeds which escape, numbers are washed down the hills by the first heavy rains of the monsoon. These collect in the valleys, and it is here that groups of seedlings and young trees are frequently found. A portion of the seed remains on the tree ; this falls gradually after the rains have commenced, and thus escapes the fires of the hot season. The germination of the seed is slow and uncertain; a large amount of moisture is needed to saturate the spongy covering; many seeds do not germinate until the second or third year, and many do not come up at all.

The bark of the stem is about half an inch thick, grey or brownish grey, the sap wood white; the heartwood of the green tree has a pleasant and strong aromatic fragrance and a beautiful golden-yellow colour, which on seasoning soon darkens into brown, mottled with darker streaks. The timber retains its aromatic fragrance to a great age. On a transverse section the wood is marked by large pores, which are more numerous and larger in the spring wood, or the inner belt of each annual ring, while they are less numerous and smaller in the autumn wood or outer belt. In this manner the growth of each successive year is marked in the wood, and the age of a tree may be determined by counting the annual rings.

The principal value of teak timber for use in warm countries is its extraordinary durability. In India and in Burmah beams of the wood in good preservation are often found in buildings several centuries old, and instances are known of teak beams having lasted more than a thousand years. [4] Being one of the few Indian timbers

- ↑ The Sanskrit name of teak is saka, and it is certain that in India teak has been known and used largely for considerably more than 2000 years. In Persia teak was used nearly 2000 years ago, and the town of Siraf on the Persian Gulf was entirely built of it. Saj is the name in Arabic and Persian; and in Hindi, Mahratti, and the other modern languages derived from Sanskrit the tree is called sag, sagwan. In the Dravidian languages the name is teka, and the Portuguese, adopting this, called it teke, teca, whence the English name.

- ↑ The rate in the London market since 1860 has fluctuated between £10 and £15 per load of 50 cubic feet.

- ↑ Hortus Malabaricus, vol. iv. tab. 27, 1683.

- ↑ In one of the oldest buildings among the ruins of the old city of Vijayanagar, on the banks of the Tungabhadra in southern India, the superstructure is supported by planks of teakwood 112 inches thick. These planks were examined in 1881; they were in a good state of