Small French clocks, which generally have the striking part made in this way, very commonly strike the half hours also, by having a wide slit, like that for one o'clock, in the locking-plate at every hour. But such clocks are unfit for any place except a room, as they strike one three times between 12 and 2, and accordingly turret clocks, or even large house clocks, are never made so. Sir E. Beckett has lately introduced the plan of making turret clocks strike one at all the half hours except 12.V and 1

In all cases the locking-plate must be considered as divided into as many parts as the number of blows to bo struck in 12 hours, i.e., 78, 90, or 88, according as half hours are or are not struck; and it must have the same number of teeth, driven by a pinion on the striking wheel arbor of as many teeth as the striking cams, or in the same ratio.

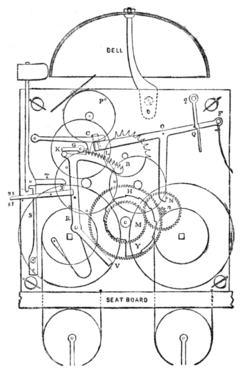

Fig. 15 is a front view of a common English house clock with the face taken off, showing the repeating or rack striking movement. Here, as in fig. 1, M is the hourwheel, on the pipe of which the minute-hand is set, N the reversed hour- wheel, and n its pinion, driving the 12-hour wheel H, on whose socket is fixed what is called the snail Y, which belongs to the striking work exclusively. The hammer is raised by the eight pins in the rim of the second wheel in the striking train, in the manner which is obvious.

The hammer does not quite touch the bell, as it would jar in striking if it did, and prevent the full sound; and if you observe the form of the hammer-shank at the arbor where the spring S acts upon it, you will see that the spring both drives the hammer against the bell when the tail T is raised, and also checks it just before it reaches the bell, and so the blow on the bell is given by the hammer having acquired momentum enough to go a little farther than its place of rest. Sometimes two springs are used, one for impelling the hammer, and the other for checking it. A piece of vulcanized India-rubber, tied round the pillar just where the hammer-shank nearly touches it, forms as good a check spring as anything. But nothing will check the chattering of a heavy hammer, except making it lean forward so as to act, partially at least, by its weight. The pinion of the striking-wheel generally has eight leaves, the same number as the pius; and as a clock strikes 78 blows in 12 hours, the great wheel will turn in that time if ifc has 78 teeth instead of 96, which the great wheel of the going part has for a centre pinion of eight. The striking-wheel, drives the wheel above it once round for each blow, and that wheel drives a fourth (in which you observe a single pin P). six, or any other integral number of turns, for one turn of its own, and that drives a fan-fly to moderate the velocity of the train by the resistance of the air, an expedient at least as old as De Vick's clock in 1370.