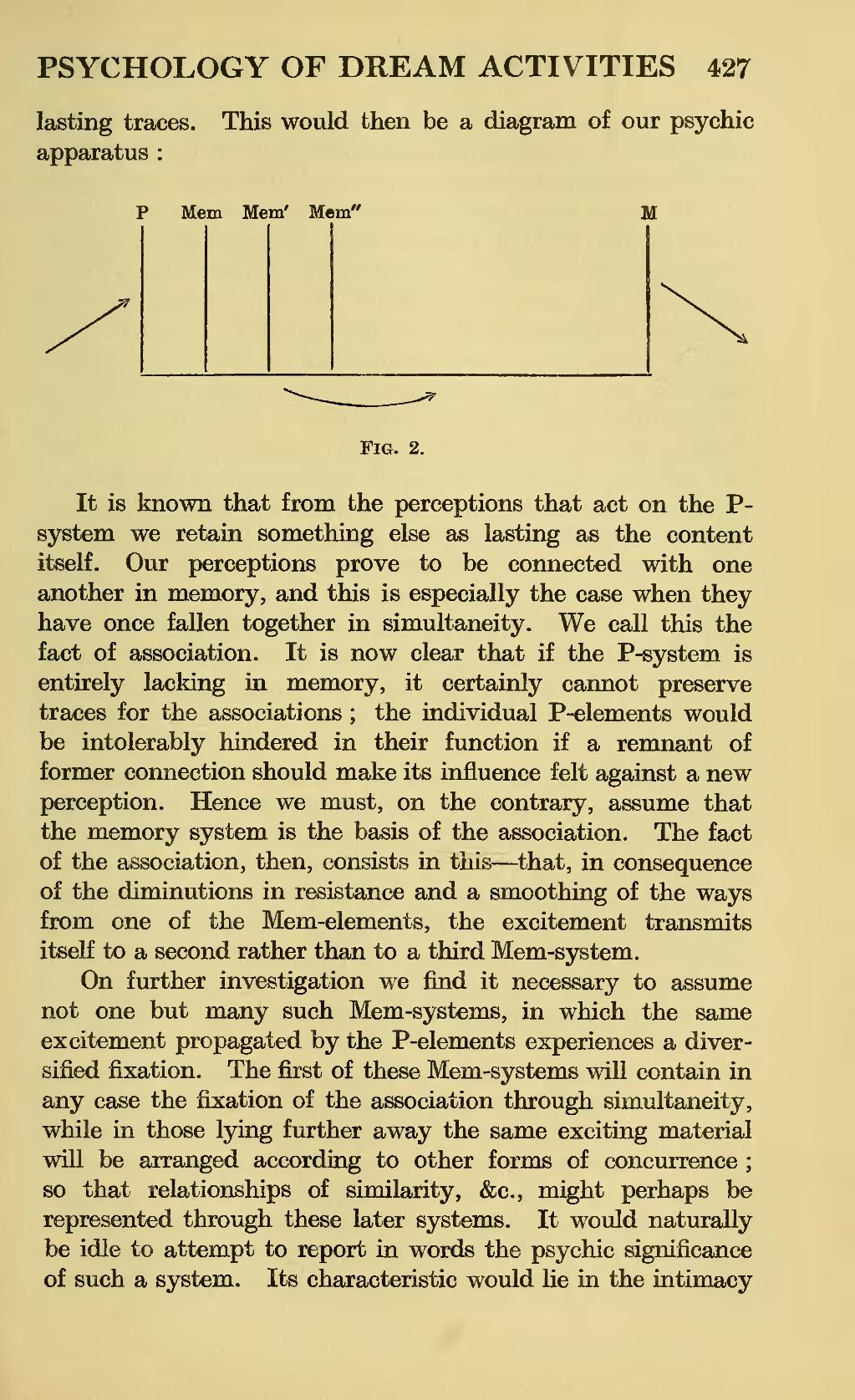

lasting traces. This would then be a diagram of our psychic apparatus:

Fig. 2.

It is known that from the perceptions that act on the P-system we retain something else as lasting as the content itself. Our perceptions prove to be connected with one another in memory, and this is especially the case when they have once fallen together in simultaneity. We call this the fact of association. It is now clear that if the P-system is entirely lacking in memory, it certainly cannot preserve traces for the associations; the individual P-elements would be intolerably hindered in their function if a remnant of former connection should make its influence felt against a new perception. Hence we must, on the contrary, assume that the memory system is the basis of the association. The fact of the association, then, consists in this—that, in consequence of the diminutions in resistance and a smoothing of the ways from one of the Mem-elements, the excitement transmits itself to a second rather than to a third Mem-system.

On further investigation we find it necessary to assume not one but many such Mem-systems, in which the same excitement propagated by the P-elements experiences a diversified fixation. The first of these Mem-systems will contain in any case the fixation of the association through simultaneity, while in those lying further away the same exciting material will be arranged according to other forms of concurrence; so that relationships of similarity, &c., might perhaps be represented through these later systems. It would naturally be idle to attempt to report in words the psychic significance of such a system. Its characteristic would lie in the intimacy