It will be seen that modifications are made in the second pair of entries; in bar 7 of our extract the close of the first subject is transferred from the bass to the treble. We have already seen the same thing (§ 271) in the case of a countersubject. A little later we find the two subjects combined in a different manner.

Here the first half of the first subject serves as a counterpoint to the second half of the second subject—a combination which we just now remarked (§ 381) was very seldom possible. But almost anything seems to have been possible to Bach. The whole fugue which we have been describing is a marvel of scientific contrivance, though we do not recommend students to imitate the consecutive seconds seen in the last bar but one of our last example.

391. One of the most perfect examples, as regards its form, of this kind of double fugue is an organ fugue by Bach in C minor. The piece is too long to quote here; it will be found in the Peter's Edition of Bach's Organ Works, Vol. IV., p. 36, to which we refer the student, confining ourselves here to a short analysis of the piece. It will be seen to differ considerably from the examples already described.

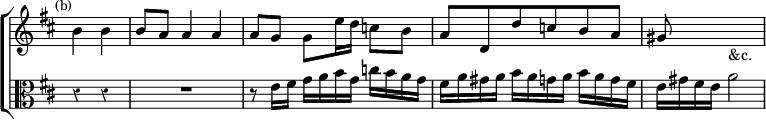

392. The first subject of the fugue, which is in four parts, is

J. S. Bach. Organ Fugue in C minor.

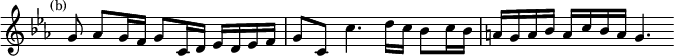

This subject receives a regular exposition (bars 1–14) followed by an episode of four bars. To this succeed four isolated entries in the keys of G minor (bar 18), E flat major (bar 23), and C minor (bars 29 and 34). After a full close in G minor, with the "Tierce de Picardie," the second subject is announced (bar 37):

This subject, like the first, has a complete exposition, the second and third entries of which are divided by a codetta (bars 42, 43). This second exposition ends in bar 49, and is followed by entries of subject or answer in G minor (bar 49), C minor (bar 52), F minor (bar 55), C minor (bar 57); then, after an episode