generally are among the most beautiful in nature, and while no artist could do justice to such a subject, much less a lithographic plate, such a plate (Plate II) may be used to recall the more striking characteristics.

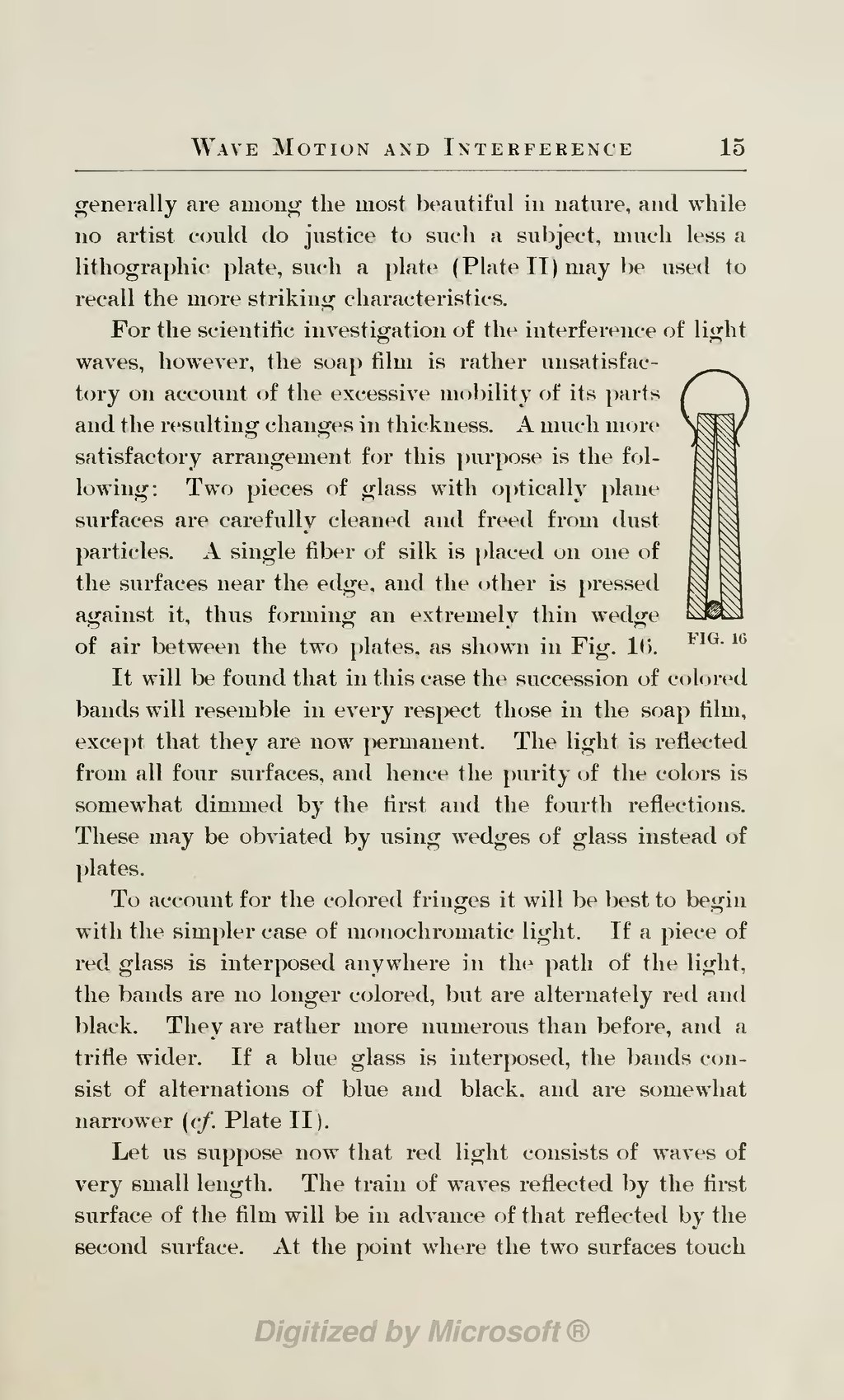

For the scientific investigation of the interference of light waves, however, the soap film is rather unsatisfactory  FIG. 16on account of the excessive mobility of its parts and the resulting changes in thickness. A much more satisfactory arrangement for this purpose is the following: Two pieces of glass with optically plane surfaces are carefully cleaned and freed from dust particles. A single fiber of silk is placed on one of the surfaces near the edge, and the other is pressed against it, thus forming an extremely thin wedge of air between the two plates, as shown in Fig. 16.

FIG. 16on account of the excessive mobility of its parts and the resulting changes in thickness. A much more satisfactory arrangement for this purpose is the following: Two pieces of glass with optically plane surfaces are carefully cleaned and freed from dust particles. A single fiber of silk is placed on one of the surfaces near the edge, and the other is pressed against it, thus forming an extremely thin wedge of air between the two plates, as shown in Fig. 16.

It will be found that in this case the succession of colored bands will resemble in every respect those in the soap film, except that they are now permanent. The light is reflected from all four surfaces, and hence the purity of the colors is somewhat dimmed by the first and the fourth reflections. These may be obviated by using wedges of glass instead of plates.

To account for the colored fringes it will be best to begin with the simpler case of monochromatic light. If a piece of red glass is interposed anywhere in the path of the light, the bands are no longer colored, but are alternately red and black. They are rather more numerous than before, and a trifle wider. If a blue glass is interposed, the bands consist of alternations of blue and black, and are somewhat narrower (cf. Plate II).

Let us suppose now that red light consists of waves of very small length. The train of waves reflected by the first surface of the film will be in advance of that reflected by the second surface. At the point where the two surfaces touch