ently not due to real resemblance. What has happened in the Monotremata is, that the prescapular fossa is so enormously expanded that it occupies the whole of the inner side of the blade-bone, while the subscapular fossa which, so to speak, should occupy that situation, has been thus pushed round to the front, where it is divided from the postscapular fossa by a slight ridge only.

The clavicle is a bone which varies much in mammals. It is sometimes indeed, as in the Ungulata, entirely absent; in other forms it shows varying degrees of retrocession in importance; it is only in climbing, burrowing, digging, and flying mammals that it is really well developed.

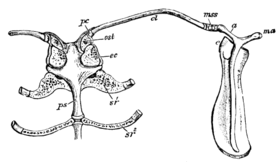

Fig. 29.—Shoulder girdle, with upper end of sternum (inner surface) of Shrew (Sorex), after Parker, × 7. a, Acromion; c, coracoid; cl, clavicle; ec, partially ossified "epicoracoid" of Parker, or rudiment of the sternal extremity of the coracoid; ma, metacromial process; mss, ossified "mesoscapular segment"; ost, omosternum; pc, rudiment of precoracoid (Parker); ps, presternum; sr1, first sternal rib; sr2, second sternal rib. (From Flower's Osteology.)

In the higher Mammalia the coracoid[1] is present, but does not reach the sternum as in the Monotremata. It is known to human anatomists as the coracoid process of the scapula. It has been found, however, by Professor Howes[2] and others, that this process really consists of two separate centres of ossification, forming two separate bonelets, which in the adult become firmly ankylosed to each other and to the scapula. These two separate bones have been met with in the embryo of Lepus, Sciurus, and the young of various other mammals belonging to very diverse orders, such as Edentates and Primates. The separation even occasionally persists in the adult. The question is, What is the relation of these bonelets to the coracoid of the Monotremata and to the corresponding regions of reptiles? Professor Howes terms the lower patch of bone the metacoracoid and the upper the epicoracoid;