just overlooking the point where the Lynhope burn runs into that water. Here, on the southern declivity of the hill of Greenshaw, by a moderate climb through the mountain fern, we reach the rocky platform of the Celtic town with its two dependencies, which form a group of fortified places of habitation. The situation is well chosen, for at a height above the level of the sea where the winds rage in full force it is so fixed as to be sheltered by the surrounding hills; the upper mass of Greenshaw hill and the great crag-crowned hill of Dunmore shelter its site on the north, the hill of Ritta performs the same office to the westward, and a little higher up the course of the Breamish are Standrop—its sides strewn with huge boulders, like the relics of some battle of primeval giants,—and Hedgehope, in altitude second only to its neighbouring height the main Cheviot. Facing its site is the contracted valley of the Breamish, with the scree-strewn sides of Harthope, the Alnham moors rising in the direction of Shillmoor, and eastward the steep heights of the Ingram hills, and Brough Law (where the Breamish escapes from its mountain barriers through a narrow gorge), with Bleakhope and Hogden in the further distance. Thus overlooked, the Celtic stronghold would, at a glance, seem to be placed at a disadvantage with relation to the commanding heights by which it is surrounded, especially on the north, where, as regards the upper fork, which lies immediately under the steep declivity of Greenshaw, its inhabitants might easily have been driven out by rolling down upon them the great boulder-stones which lie ready to hand; but it is to be understood from existing traces that the approach to the upper ridges of the hill had been sufficiently protected, and for the same reason we may account for the superior strength of the ramparts of the larger town on the lower face of the hill, where the approach is more open and access less easily prevented at a time when the scope of missiles was limited.

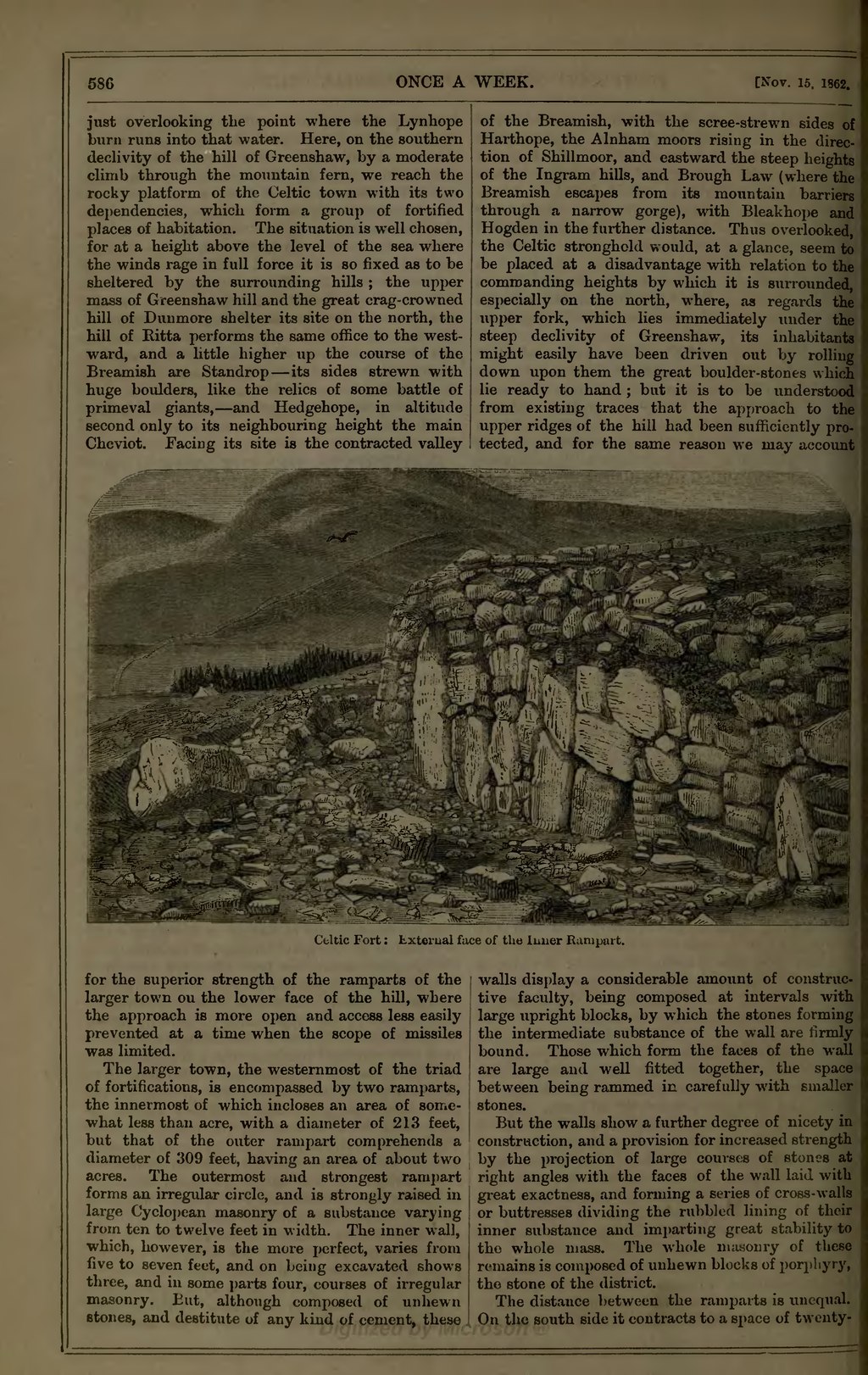

The larger town, the westernmost of the triad of fortifications, is encompassed by two ramparts, the innermost of which incloses an area of somewhat less than acre, with a diameter of 213 feet, but that of the outer rampart comprehends a diameter of 309 feet, having an area of about two acres. The outermost and strongest rampart forms an irregular circle, and is strongly raised in large Cyclopean masonry of a substance varying from ten to twelve feet in width. The inner wall, which, however, is the more perfect, varies from five to seven feet, and on being excavated shows three, and in some parts four, courses of irregular masonry. But, although composed of unhewn stones, and destitute of any kind of cement, these walls display a considerable amount of constructive faculty, being composed at intervals with large upright blocks, by which the stones forming the intermediate substance of the wall are firmly bound. Those which form the faces of the wall are large and well fitted together, the space between being rammed in carefully with smaller stones.

But the walls show a further degree of nicety in construction, and a provision for increased strength by the projection of large courses of stones at right angles with the faces of the wall laid with great exactness, and forming a series of cross-walls or buttresses dividing the rubbled lining of their inner substance and imparting great stability to the whole mass. The whole masonry of these remains is composed of unhewn blocks of porphyry, the stone of the district.

The distance between the ramparts is unequal. On the south side it contracts to a space of twenty-