chromatic compositions for decorative purposes or for paintings, artists of all times have necessarily been controlled to a considerable extent by the laws of contrast, which they have instinctively obeyed, just as children in walking and leaping obey the law of gravitation, though hardly conscious of its existence.

The phenomena of contrast as exhibited by colors which are intense, pure, and brilliant, are to be explained to a considerable extent by the fatigue of the nerves, as set forth in the early part of the present chapter. The changes in color and saturation become particularly conspicuous after somewhat prolonged observation, and are often attended with a peculiar soft glimmering, which seems to float over the surfaces, and, in the case of colors that are far apart in the chromatic circle, to lend them a lustrous appearance. Still, upon the whole, the effects of contrast with brilliant colors are often not strongly marked at first glance, from the circumstance that the colors, by virtue of their actual intensity and strength, are able to resist these changes, and it often requires a practiced eye to detect them with certainty. The case is quite otherwise with colors which are more or less pale or dark—that is, which are deficient in saturation, or luminosity, or both. Here the original sensation produced upon the eye is comparatively feeble, and it is hence more readily modified by contrast. In these cases the fatigue of the nerves of the retina plays but a very subordinate part, as we recognize the effects of contrast at the first glance. We have to

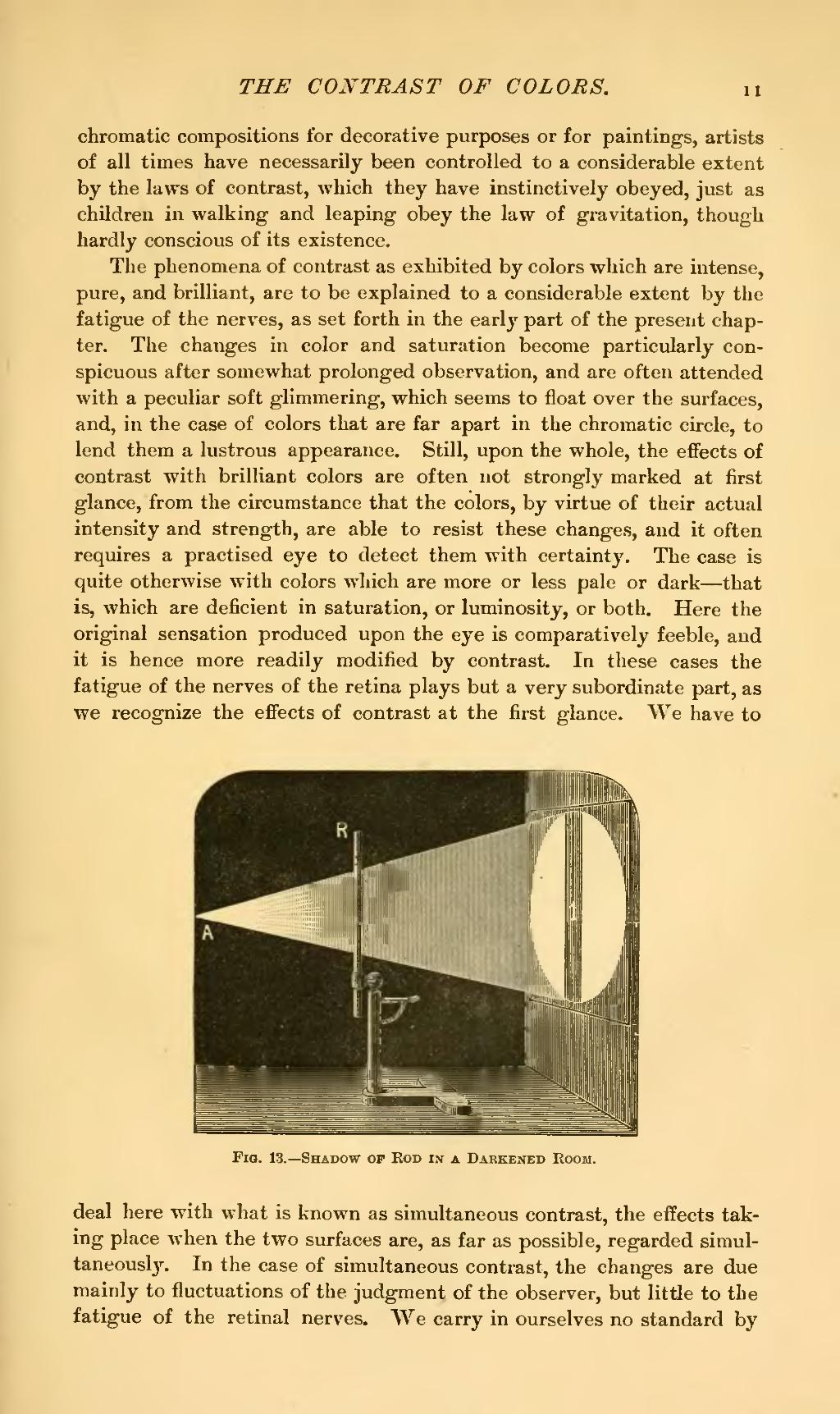

Fig. 13.—Shadow of Rod in a Darkened Room.

deal here with what is known as simultaneous contrast, the effects taking place when the two surfaces are, as far as possible, regarded simultaneously. In the case of simultaneous contrast, the changes are due mainly to fluctuations of the judgment of the observer, but little to the fatigue of the retinal nerves. We carry in ourselves no standard by