tual Gnetaceæ. The true phanerogams, the angiosperms, appeared much later. Further, the carboniferous flora comprehended some Cycadeæ, such as the Noeggerathia foliosa and a pterophyllum discovered recently by M. Grand' Eury; some true conifers, as the Walchia; some Taxineæ more or less like our Ginkgo; and, finally, a great number of Cordaïticæ, most of which were great trees so perfectly preserved that they could not only be placed at the head of the gymnosperms, but their affinities with the class of angiosperms could also be observed.

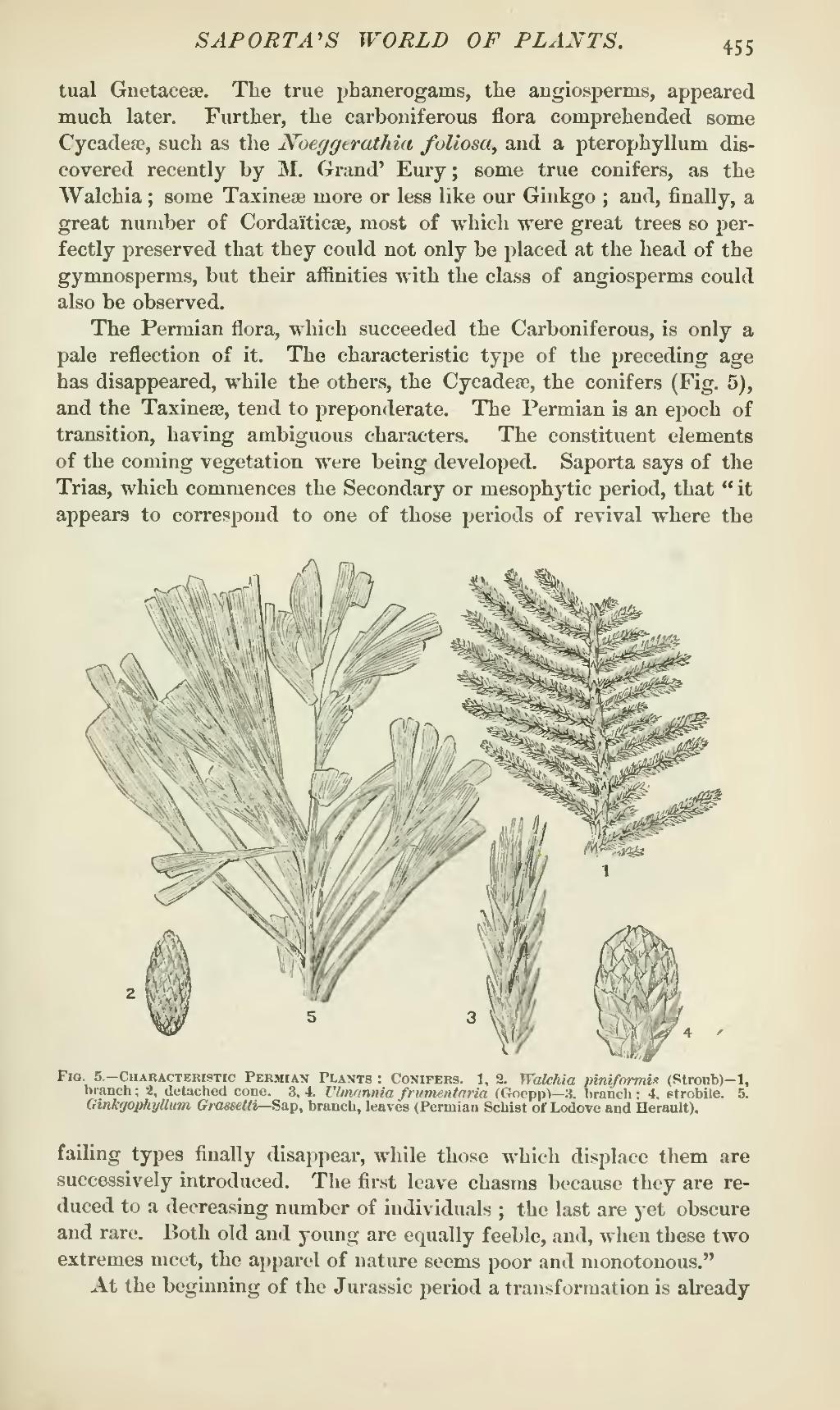

The Permian flora, which succeeded the Carboniferous, is only a pale reflection of it. The characteristic type of the preceding age has disappeared, while the others, the Cycadeæ, the conifers (Fig. 5), and the Taxineæ, tend to preponderate. The Permian is an epoch of transition, having ambiguous characters. The constituent elements of the coming vegetation were being developed. Saporta says of the Trias, which commences the Secondary or mesophytic period, that "it appears to correspond to one of those periods of revival where the

Fig. 5.—Characteristic Permian Plants: Conifers. 1, 2. Walchia piniformis (Stroub)—l, branch; 2, detached cone. 3, 4. Ulmannia frumentaria (Goepp)—3. branch: 4. strobile. 5. Ginkgophyllum Grassetti—Sap, branch, leaves (Permian Schist of Lodove and Herault).

failing types finally disappear, while those which displace them are successively introduced. The first leave chasms because they are reduced to a decreasing number of individuals; the last are yet obscure and rare. Both old and young are equally feeble, and, when these two extremes meet, the apparel of nature seems poor and monotonous."

At the beginning of the Jurassic period a transformation is already