Through a third hole passed a horizontal glass tube. Now, when the kidney increased in volume it drove the oil into the horizontal glass tube, when it contracted the oil was sucked back again—hence by measuring the distance the oil advanced or retreated, the corresponding increase or diminution of size of the kidney could be exactly determined.

The physiological importance of the changes of the volume of a single organ was thus clearly established. If it was possible to record those changes in an isolated organ, why not try to record them of a part, a limb still connected with the body? The possibility conceived was soon accomplished. The apparatus was altered and improved. In its new form it could be used to record the changes in the volume of the human forearm by tracing them upon a piece of paper in the shape of a series of curves.

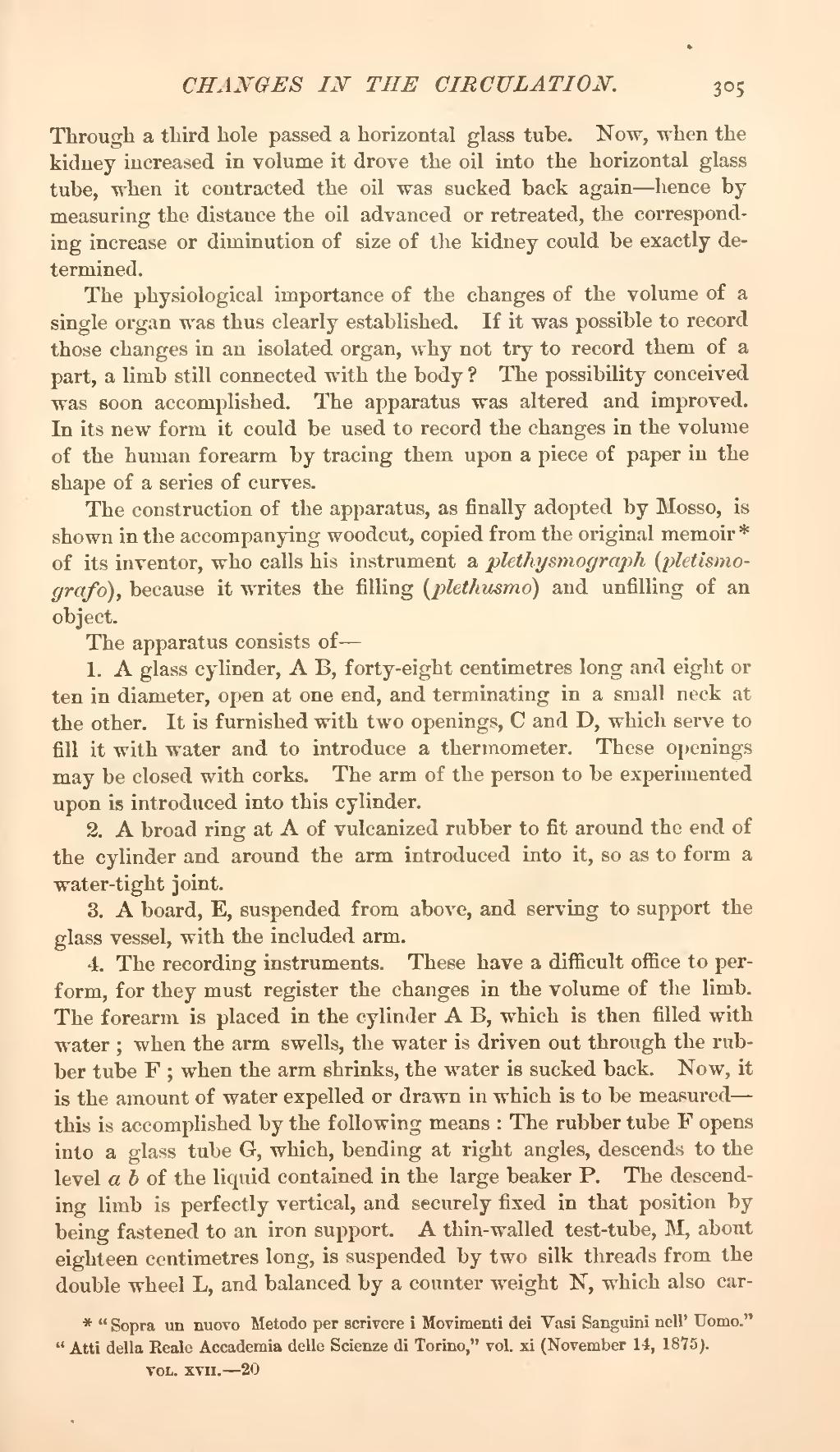

The construction of the apparatus, as finally adopted by Mosso, is shown in the accompanying woodcut, copied from the original memoir[1] of its inventor, who calls his instrument a plethysmograph (pletismografo), because it writes the filling (plethitsmo) and unfilling of an object.

The apparatus consists of—

1. A glass cylinder, A B, forty-eight centimetres long and eight or ten in diameter, open at one end, and terminating in a small neck at the other. It is furnished with two openings, C and D, which serve to fill it with water and to introduce a thermometer. These openings may be closed with corks. The arm of the person to be experimented upon is introduced into this cylinder.

2. A broad ring at A of vulcanized rubber to fit around the end of the cylinder and around the arm introduced into it, so as to form a water-tight joint.

3. A board, E, suspended from above, and serving to support the glass vessel, with the included arm.

4. The recording instruments. These have a difficult office to perform, for they must register the changes in the volume of the limb. The forearm is placed in the cylinder A B, which is then filled with water; when the arm swells, the water is driven out through the rubber tube F; when the arm shrinks, the water is sucked back. Now, it is the amount of water expelled or drawn in which is to be measured—this is accomplished by the following means: The rubber tube F opens into a glass tube G, which, bending at right angles, descends to the level a b of the liquid contained in the large beaker P. The descending limb is perfectly vertical, and securely fixed in that position by being fastened to an iron support. A thin-walled test-tube, M, about eighteen centimetres long, is suspended by two silk threads from the double wheel L, and balanced by a counter weight N, which also car-

- ↑ "Sopra un nuovo Metodo per scrivere i Movimenti dei Vasi Sanguini nell' Uomo." "Atti della Reale Accademia delle Scienze di Torino," vol. xi (November 14, 1875).