sleep does not so much concern the inquiry. The night-movements of leaves result from circumnutation modified by changes of light and darkness, and also by heredity; and, as Darwin has proved, they are chiefly of use to the plant in diminishing the loss of heat by radiation. Therefore, he says, no movement deserves to be called nyctitropic unless it has been acquired for this purpose. As some leaves and cotyledons bend upward only a little at night, the question arises. At what angle does the diminished radiation warrant the use of this term? He takes an arbitrary limit of 60°, above or below the horizon, as any less angular rise and fall would be of slight significance. Nyctitropic movements are easily affected by surrounding conditions of moisture and temperature, and in many genera it is indispensable that the leaves should be well illuminated during the day. From the very wide list of genera experimented upon, it follows that the habit of sleeping "is common to some few plants throughout the whole vascular series."

Darwin first considers the sleep of cotyledons, having observed the positions during the day and night of the representatives of one hundred and fifty-three genera. Some ten pages are given up to remarks upon this subject. We give his account of the behavior of the cotyledons of Trifolium strictum as it is illustrated by a picture of the diurnal and nocturnal positions they assume.

"On the first day after germination, the cotyledons stood at noon horizontally, and at night rose to only about 45° above the horizon. Four days afterward the seedlings were again observed at night, and now the blades stood vertically and were in contact, excepting the tips, which were much deflexed, so that they faced the zenith. At this age the petioles are curved upward, and at night, when the bases of the blades are in contact, the two petioles form a vertical ring around the plumule. The cotyledons continued to act in nearly

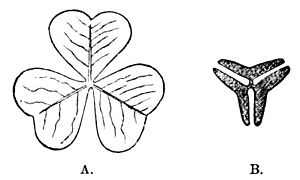

Fig. 6.—Oxalis acetosella: A, leaf seen from vertically above; B, diagram of leaf asleep, also seen from vertically above.

the same manner for eight or ten days from the time of germination, but the petioles had become straight and were much lengthened. After twelve or fourteen days the first true leaf was formed, and during the next fortnight a remarkable movement was repeatedly observed. At I, Fig. 5, we have a sketch made in the middle of the day, of a seedling a fortnight old. The two cotyledons, of which