of gills in the different groups of fishes. Their origin from the food-tract is clearly shown in the lowest fish, the worm-like Amphioxus, which has gills formed from a large, barrel-shaped pharynx pierced with transverse slits through which the water is drawn by cilia (Fig. 2, page 645 of the September, 1881, "Monthly"). This creature differs from all other known vertebrates in the possession of cilia as the means of renewing the water.

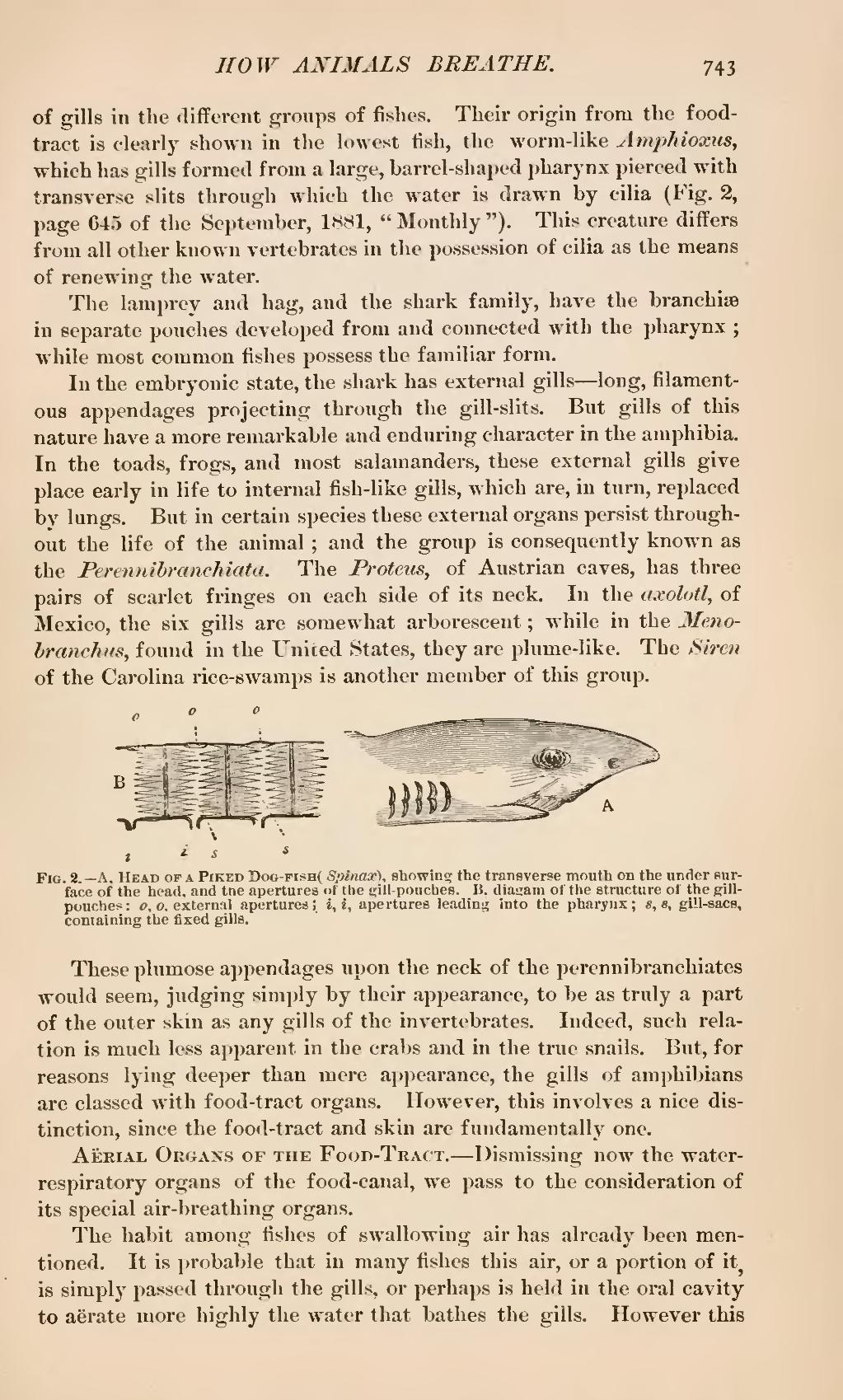

The lamprey and hag, and the shark family, have the branchiæ in separate pouches developed from and connected with the pharynx; while most common fishes possess the familiar form.

In the embryonic state, the shark has external gills—long, filamentous appendages projecting through the gill-slits. But gills of this nature have a more remarkable and enduring character in the amphibia. In the toads, frogs, and most salamanders, these external gills give place early in life to internal fish-like gills, which are, in turn, replaced by lungs. But in certain species these external organs persist throughout the life of the animal; and the group is consequently known as the Perennibranchiata. The Proteus, of Austrian caves, has three pairs of scarlet fringes on each side of its neck. In the axolotl, of Mexico, the six gills are somewhat arborescent; while in the Menobranchus, found in the United States, they are plume-like. The Siren of the Carolina rice-swamps is another member of this group.

These plumose appendages upon the neck of the perennibranchiates would seem, judging simply by their appearance, to be as truly a part of the outer skin as any gills of the invertebrates. Indeed, such relation is much less apparent in the crabs and in the true snails. But, for reasons lying deeper than mere appearance, the gills of amphibians are classed with food-tract organs. However, this involves a nice distinction, since the food-tract and skin are fundamentally one.

Aërial Organs of the Food-Tract.—Dismissing now the water-respiratory organs of the food-canal, we pass to the consideration of its special air-breathing organs.

The habit among fishes of swallowing air has already been mentioned. It is probable that in many fishes this air, or a portion of it is simply passed through the gills, or perhaps is held in the oral cavity to aërate more highly the water that bathes the gills. However this