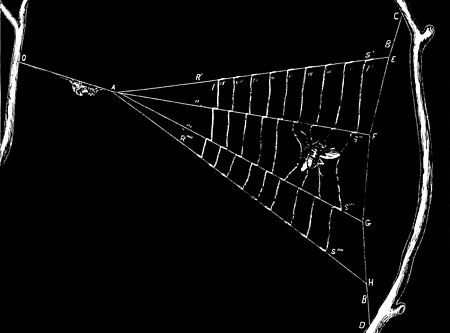

aërial structures, succeeding one another at short intervals and giving curious effects to the landscape. The great spider may generally be perceived on each of these nets, either motionless or in a state of high excitement, according as it is waiting for game or struggling with it. At some periods of the year, yellow, golden-like globes may be perceived suspended from the nets. They are the cocoons containing the eggs. In building their nets over streams, the epeïras are directed by a happy instinct. In the midst of a peculiarly bushy vegetation, they seek out broad, open spaces suitable for their establishments. In such spaces they are safest from their voracious enemies, and are at the same time conveniently situated to capture the insects that are their food. Not only are mammals and insects, lizards and birds fond of spiders, multitudes of people regard the handsome spinners as delicious meat. A large species, very abundant in the Polynesian Archipelago, is called the eatable epeïra (Epeïra edulis), and is much sought for by the islanders.

The epeïras of Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands, according to the descriptions of Captain Dupré, are among the largest and handsomest of their kind. They build vertical webs which they attach to trees and shrubs by long threads having great power of resistance. The black epeïra predominates in the island of Reunion, the gilded epeïra in Mauritius—a magnificent animal, whose body, two inches or more in length, bears on the back a large space of bright yellow, relieved by two rows of black dots. The Madagascar species, which the Malagasy eat with relish, is yet more highly distinguished by the gayety of its dress. Its black dorsal buckler is clothed with a silvery pubescence; on its abdomen are harmoniously combined the colors of ebony, gold, and silver, and its legs are a fiery red. The disproportion in the size