We are constantly increasing our store of mental images, and when one contrasts the small number of such images in the brain of a common uneducated day-laborer with the myriads in the brain of one who has traveled widely, has become familiar with

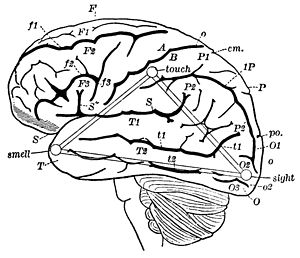

Fig. 6.—The Location of the Memory-Pictures in the Mental Image of a Rose on the Brain Surface. The different memory-pictures are joined by association fibers. the stores of information in foreign languages as well as in his own, and has cultivated his powers of observation in many different directions—for example, such a great leader of thought as Gladstone—one can not but be amazed at the capacity of work in this little organ, the brain. And if there is a physical basis for each of these mental images, is it not evident that in the brain of a Gladstone large areas must be taken up which in the laboring man are really empty? We have seen that on our brain-map there are some empty spaces. There is every reason to believe that these grow smaller as our information widens; and, if so, then, like the undiscovered country of Africa, they should really be a stimulus to efforts of further conquest.

Fig. 6.—The Location of the Memory-Pictures in the Mental Image of a Rose on the Brain Surface. The different memory-pictures are joined by association fibers. the stores of information in foreign languages as well as in his own, and has cultivated his powers of observation in many different directions—for example, such a great leader of thought as Gladstone—one can not but be amazed at the capacity of work in this little organ, the brain. And if there is a physical basis for each of these mental images, is it not evident that in the brain of a Gladstone large areas must be taken up which in the laboring man are really empty? We have seen that on our brain-map there are some empty spaces. There is every reason to believe that these grow smaller as our information widens; and, if so, then, like the undiscovered country of Africa, they should really be a stimulus to efforts of further conquest.

But this mental image of the rose, as represented in the figure, is not really a complete image until it is associated with a name. And the mental image of the name is not as simple as might at first be supposed; for you have not only learned to recognize the word "rose" when you hear it, or when you see it printed, but you have also learned to say the word and to write it, so that you really have a word-image "rose" made up of two sensory images, auditory and visual, and of two motor images, or the memory of the effort necessary to use the word in speech and in script. It is necessary to add then four more circles to the diagram to show the physical basis of the word "rose," and each of these must be placed in its own special region, which has been determined by a long series of investigations. These circles, too, must be joined together, since all the parts of the word are connected in the mind; and, finally, the word-image and the mental image, in all their parts, must also be associated (Fig. 7). Thus the complete mental image of such a simple object as a rose is made up of numerous distinct mental pictures, each joined to all the others, and each located in