objection of having the beauty of clean fruit lost under a film of fungicide that while not particularly poisonous is decidedly unpalatable, consisting of lime and sulphate of copper. A sensation was created in New York two years ago because grapes were thus marketed, and the same process for stored fruit is not here recommended, although its effectiveness as a preservative is granted.

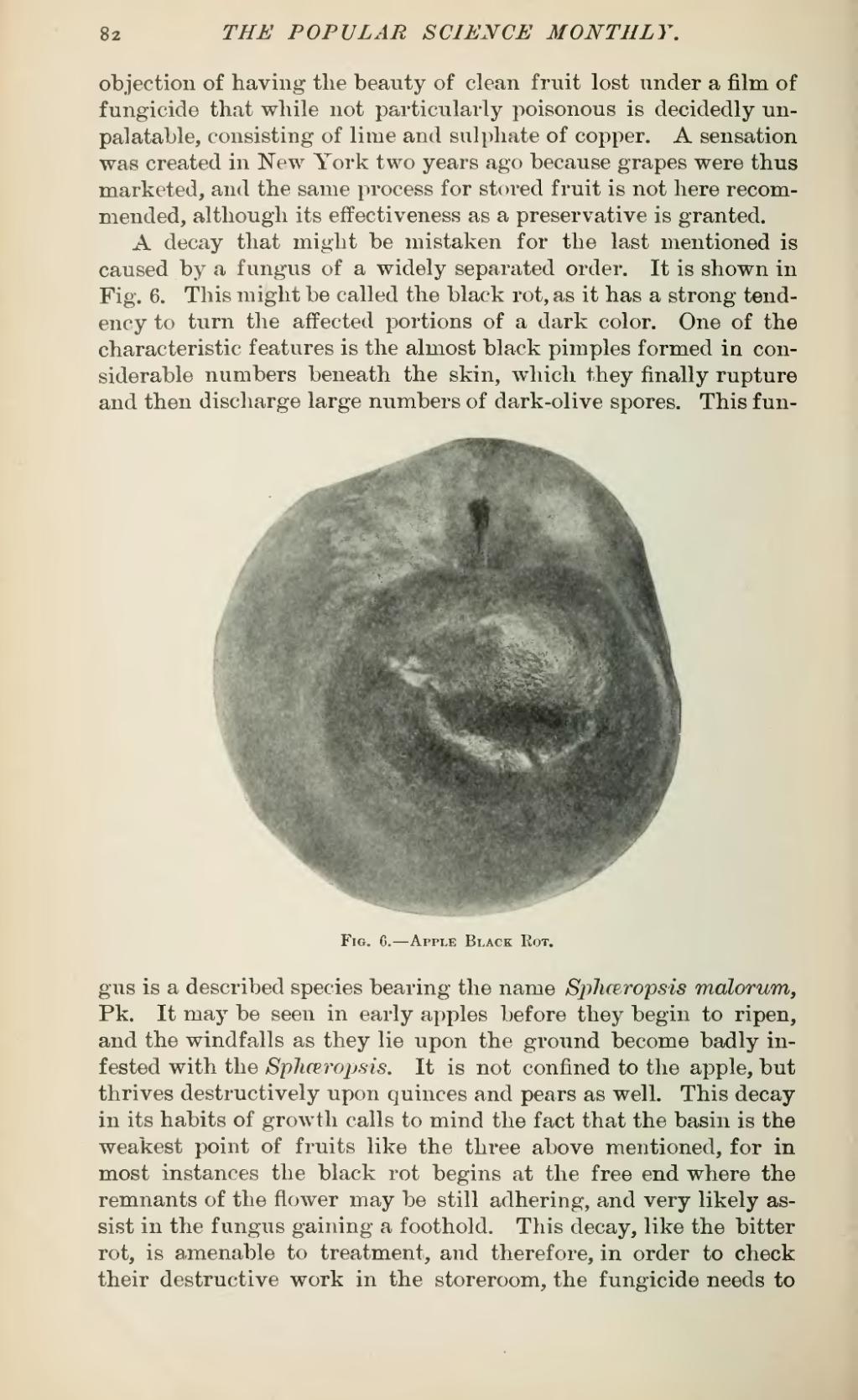

A decay that might be mistaken for the last mentioned is caused by a fungus of a widely separated order. It is shown in Fig. 6. This might be called the black rot, as it has a strong tendency to turn the affected portions of a dark color. One of the characteristic features is the almost black pimples formed in considerable numbers beneath the skin, which they finally rupture and then discharge large numbers of dark-olive spores. This fungus

Fig. 6.—Apple Black Rot.

is a described species bearing the name Sphœropsis malorum, Pk. It may be seen in early apples before they begin to ripen, and the windfalls as they lie upon the ground become badly infested with the Sphœropsis. It is not confined to the apple, but thrives destructively upon quinces and pears as well. This decay in its habits of growth calls to mind the fact that the basin is the weakest point of fruits like the three above mentioned, for in most instances the black rot begins at the free end where the remnants of the flower may be still adhering, and very likely assist in the fungus gaining a foothold. This decay, like the bitter rot, is amenable to treatment, and therefore, in order to check their destructive work in the storeroom, the fungicide needs to