This and the rarer stormy petrel and a third species, which all resemble one another very closely, are commonly known to sailors as "Mother Carey's chickens," a name quite generally applied  Fig. 3.—Common Porpoise. to this family, and probably suggested, as Wilson observes, by their mysterious appearance before and during storms, their great power of flight, and obscure habits. The superstitious mariner may indeed have regarded his little comrades not as harbingers merely, but as agents in league with the powers of darkness, directly concerned in bringing the storm. Mother Carey is the mater cara; so with the French these birds are "oiseaux de Notre Dame." The gigantic fulmar of the Pacific is known as "Mother Carey's goose," and hence the phrase "Mother Carey is plucking her goose"—that is, "it is snowing."

Fig. 3.—Common Porpoise. to this family, and probably suggested, as Wilson observes, by their mysterious appearance before and during storms, their great power of flight, and obscure habits. The superstitious mariner may indeed have regarded his little comrades not as harbingers merely, but as agents in league with the powers of darkness, directly concerned in bringing the storm. Mother Carey is the mater cara; so with the French these birds are "oiseaux de Notre Dame." The gigantic fulmar of the Pacific is known as "Mother Carey's goose," and hence the phrase "Mother Carey is plucking her goose"—that is, "it is snowing."

While the petrels do not "carry their eggs under their wings and hatch them while resting on the sea," as seafaring men affirmed, yet their domestic life seems to be curtailed as much as possible. They nest in cavities in rocks along the coast or in burrows in the ground, laying a single white egg. This species is said to breed in Florida and the West India islands.

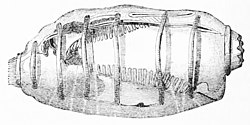

The petrel belongs to the wild wastes of the sea, as the gull belongs to the shore, and the swallow to inland districts. Sea birds are as completely helpless when driven far inland as the  Fig. 4.—Salpa. strictly land species are at sea. Every now and then we hear of some wanderer from the coast being picked up half dead from exhaustion and fright hundreds of miles from the ocean, having been shipwrecked apparently and blown in thither during a storm. A case of this kind was communicated to me some time ago by a gentleman in Sharon, Vermont, where a specimen of the dovekie, or sea dove, a common bird of the northern New England coast, was found one morning in the fall on a neighbor's porch.

Fig. 4.—Salpa. strictly land species are at sea. Every now and then we hear of some wanderer from the coast being picked up half dead from exhaustion and fright hundreds of miles from the ocean, having been shipwrecked apparently and blown in thither during a storm. A case of this kind was communicated to me some time ago by a gentleman in Sharon, Vermont, where a specimen of the dovekie, or sea dove, a common bird of the northern New England coast, was found one morning in the fall on a neighbor's porch.

The helplessness of our song birds when carried to sea is piti-