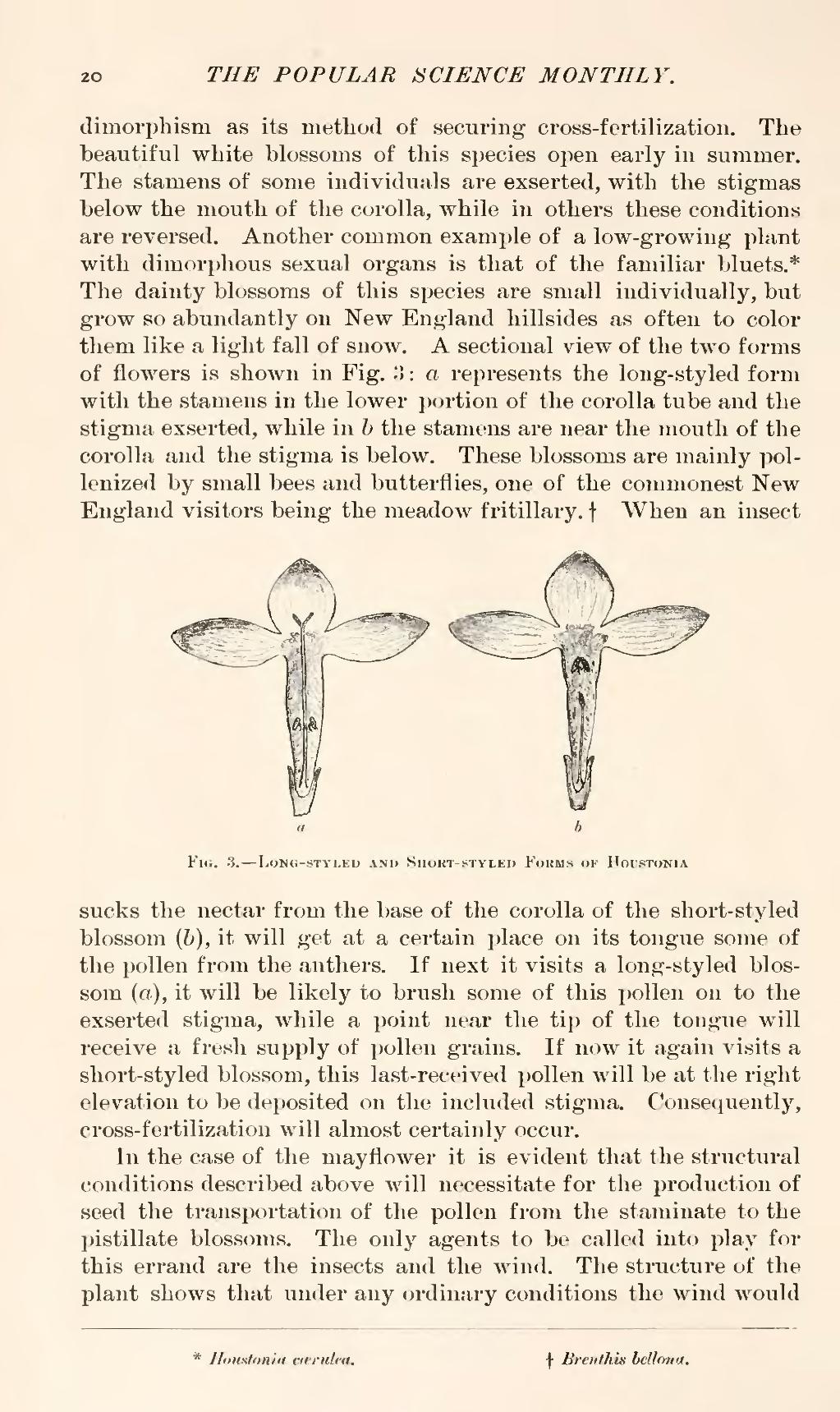

dimorphism as its method of securing cross-fertilization. The beautiful white blossoms of this species open early in summer. The stamens of some individuals are exserted, with the stigmas below the mouth of the corolla, while in others these conditions are reversed. Another common example of a low-growing plant with dimorphous sexual organs is that of the familiar bluets.[1] The dainty blossoms of this species are small individually, but grow so abundantly on New England hillsides as often to color them like a light fall of snow. A sectional view of the two forms of flowers is shown in Fig. 3: a represents the long-styled form with the stamens in the lower portion of the corolla tube and the stigma exserted, while in b the stamens are near the mouth of the corolla and the stigma is below. These blossoms are mainly pollenized by small bees and butterflies, one of the commonest New England visitors being the meadow fritillary.[2] When an insect

Fig. 3.—Long-styled and Short-styled Forms of Houstonia

sucks the nectar from the base of the corolla of the short-styled blossom (b), it will get at a certain place on its tongue some of the pollen from the anthers. If next it visits a long-styled blossom (a), it will be likely to brush some of this pollen on to the exserted stigma, while a point near the tip of the tongue will receive a fresh supply of pollen grains. If now it again visits a short-styled blossom, this last-received pollen will be at the right elevation to be deposited on the included stigma. Consequently, cross-fertilization will almost certainly occur.

In the case of the mayflower it is evident that the structural conditions described above will necessitate for the production of seed the transportation of the pollen from the staminate to the pistillate blossoms. The only agents to be called into play for this errand are the insects and the wind. The structure of the plant shows that under any ordinary conditions the wind would