able distance the movements of the mother's pencil.[1] They may be made expressive or significant in two ways. In the first place, a child may by varying the swinging movements accidentally produce an effect which suggests an idea through a remote resemblance. A little boy, when two years and two months, was one day playing in this wise with the pencil, and happening to make a sort of curling line, shouted with excited glee, "Puff, puff!"—i. e., smoke. He then drew more curls with a rudimentary intention to show what he meant. In like manner, when a child happens to bend his line into something like a closed circle or ellipse, he will catch the faint resemblance to the rounded human head and exclaim, "Mamma!" or "Dada!"

But intentional drawing or designing does not always arise in this way. A child may set himself to draw, and make believe that he is drawing something when he is scribbling. This is largely an imitative play-action following the directions of the movements of another's hand. Preyer speaks of a little boy who in his second year was asked when scribbling with a pencil what

Fig. 1. he was doing and answered, "Writing houses." He was apparently making believe that his jumble of lines represented houses.[2]

Fig. 1. he was doing and answered, "Writing houses." He was apparently making believe that his jumble of lines represented houses.[2]

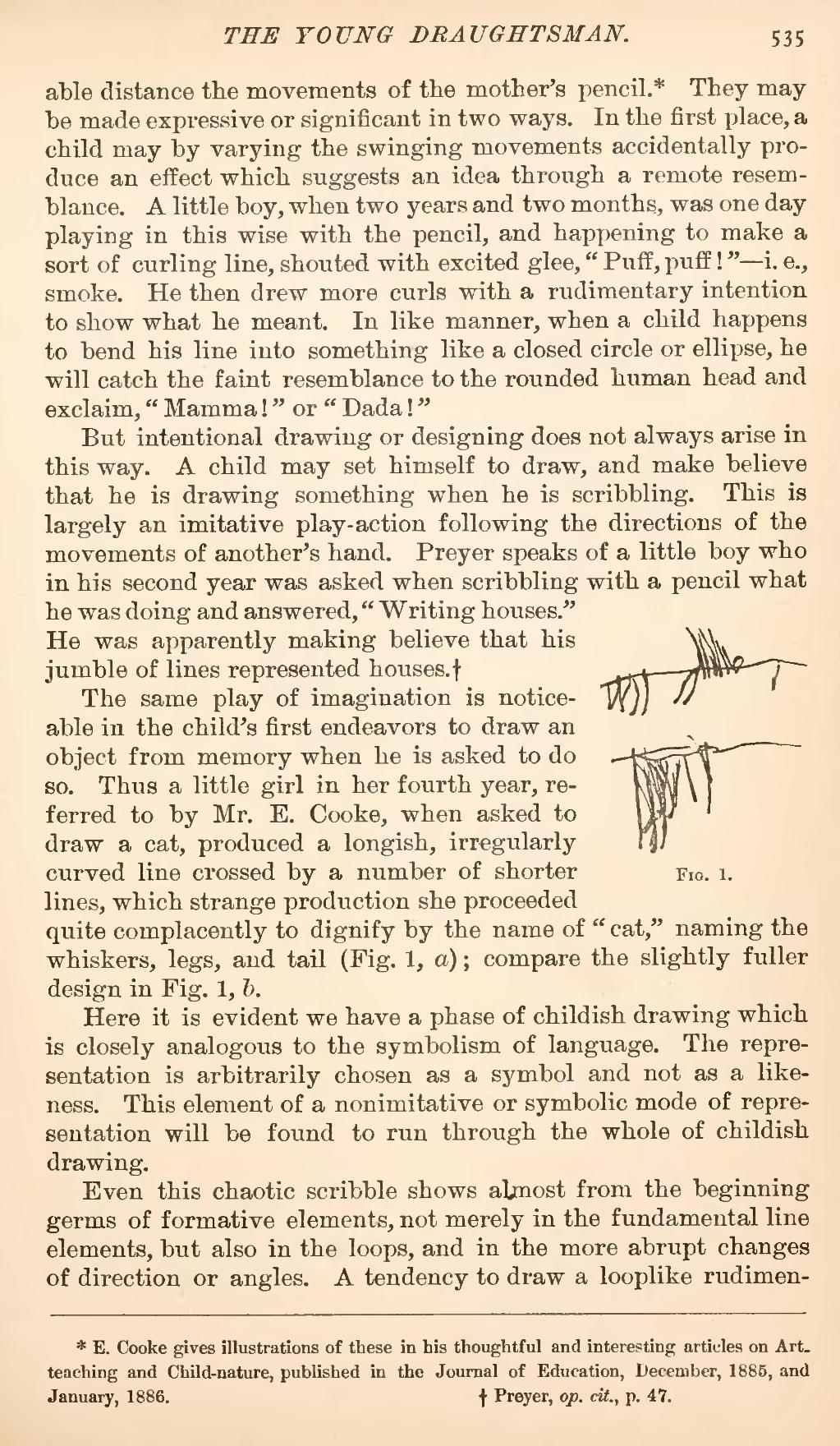

The same play of imagination is noticeable in the child's first endeavors to draw an object from memory when he is asked to do so. Thus a little girl in her fourth year, referred to by Mr. E. Cooke, when asked to draw a cat, produced a longish, irregularly curved line crossed by a number of shorter lines, which strange production she proceeded quite complacently to dignify by the name of "cat," naming the whiskers, legs, and tail (Fig. 1, a); compare the slightly fuller design in Fig. 1, b.

Here it is evident we have a phase of childish drawing which is closely analogous to the symbolism of language. The representation is arbitrarily chosen as a symbol and not as a likeness. This element of a nonimitative or symbolic mode of representation will be found to run through the whole of childish drawing.

Even this chaotic scribble shows almost from the beginning germs of formative elements, not merely in the fundamental line elements, but also in the loops, and in the more abrupt changes of direction or angles. A tendency to draw a looplike rudimen-